The cause of increasing poverty levels continues to go unquestioned

A poverty epidemic is spreading around the world. In 2022, the US experienced its largest one-year increase in the poverty rate in history. In the UK, France, Germany and Italy the story is much the same. The richest nations in the world are wealthier than ever, but all are seeing sharp increases in poverty levels. Inflation and stagnating wages have led to decreasing living standards. Society is awash with despondency, negativity and a general malaise.

It feels like the time is right for new economic ideas. Ideas that can support a social reset where the economy works for everyone, not just a rich elite. But social reset feels as far away as ever from materialising. If anything, the resurgence of the far-right in Europe, and the popularity of Donald Trump in the US, shows that voters like the idea of more freedom for markets and lower taxes on individuals.

This feels counter-intuitive when it is these kinds of policies that have led to this mess. The change we need isn’t on the horizon. And if history is anything to go by it appears that a global economic crash is required for a social reset. To understand why, we need to take a glimpse into different phases of capitalism, and what triggered previous changes in approach.

Capitalism 1.0

While capitalism is defined by the private ownership of production, there have been three distinct phases of global capitalism that have led to very different social outcomes.

The first phase — ‘Capitalism 1.0’ — dominated during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This was the first conception of liberalism, a form of capitalism that revolves around a belief that markets and private enterprise are the source of all wealth.

What adds weight to this belief is the idea that markets create ‘pareto optimal’ outcomes. That is, free markets, as Mike Berry puts it in Neoliberalism and the City, allocate available resources “so that no reallocation could make consumers better off in their own eyes without making at least one other consumer worse off in his/her eyes.”

In short, free markets work perfectly and lead to optimal outcomes for each person in the market when they are left to self-regulate. It’s for these reasons that free markets are believed to be the most efficient way to manage an economy.

According to theory, the market economy provides for every conceivable societal need and want. Free markets also create perfect competition. This means demand will always equal supply for every possible good or service, including labour.

In the real world, perfect competition would make unemployment impossible because demand for labour will always equal supply. If someone is unemployed, it must be because they chose to be unemployed.

Moving into the 1920s, liberalism seemed to be working well. In the US, the decade came to be known as the Roaring Twenties, as it was a time of economic expansion, new inventions, and consumer culture.

But when we say ‘working well’, the real question is, working well for who? Certainly not the working class. With limited unions and employment rights virtually non-existent, workers were at the mercy of the capitalist manufacturers, who could pay low wages, and do, what they wanted.

The unravelling

The result was brutal levels of inequality. The economist Thomas Piketty shows that in 1928 (the year when inequality peaked during the twentieth century), the richest 0.1% of Americans owned over 45% of all wealth, while more than 60% of Americans lived below the poverty line.

Rather than the meritocracy it claimed to create, liberalism created an environment where individuals who had a lot, had the opportunity to make a lot more, while those who had too little (and worked for those who had a lot) were trapped in a cycle of poverty.

This was ultimately what was intended. To create a landscape where a rich elite could suck up the fruits of economic activity, leaving everyone else fighting over the scraps.

The unravelling of liberalism was not due to a social epiphany that if the fruits of production are distributed more evenly it leads to a more harmonious society for all. No.

Liberalism unravelled due to the 1929 stock market crash, an event no one saw coming. The crash triggered The Great Depression, leaving the global economy in ruins. In the US, where the impacts were particularly brutal, the depression left a quarter of all adults unemployed.

The impacts of the crash reverberated throughout the world during the 1930s and led to festering social conditions that were a factor in sparking the outbreak of the Second World War. That war resulted in an estimated 70 to 85 million deaths and changed the face of the world.

It took a depression that resulted in a world war to make people realise that giving markets too much freedom is dangerous because, while in theory markets can’t fail, time and time again, markets do fail. And when they fail society has to pick up the pieces.

Capitalism 2.0

To reignite the economy after the depression, it was believed governments had to play a far more active role in it. Spearheading the transformation of capitalism was the idea of a ‘mixed economy’.

The mixed economy was the brainchild of the British economist John Maynard Keynes. Keynesian economics centred on ‘aggregate demand’. Keynes argued the total sum of spending by households, businesses, and the government was the most important driving force in an economy. Underlying ‘Capitalism 2.0’ was a balance between the public and private sectors.

The mixed economy, underpinned by the regulation of markets and a strong welfare state, came to dominate in the West after the Second World War.

As the economist Dani Rodrik puts it in The Globalisation Paradox, “this “mixed-economy” model was the crowning achievement of the twentieth century. The new balance that it established between states and markets underpinned an unprecedented period of social cohesion, stability, and prosperity in the advanced economies that lasted until the mid-1970s.”

Capitalism hasn’t always had things its own way on the global stage. Capitalism 2.0 faced an ideological competitor — communism. The Cold War was the front line of this battle of ideologies. In one corner there was the United States — the embodiment of capitalism, in the other, was the Soviet Union — the custodian of communism.

As the Cold War was heating up, a small group of economists, including Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman and Frank Knight, met in the Swiss resort of Mont Pèlerin in 1947. Their aim? To establish what they called the ‘neoliberal’ agenda.

In its statement of aims, The Mont Pelerin Society (as they christened themselves) declared, “the central values of civilization are in danger.” The danger was from the growing influence and reach of the Soviet Union and state totalitarianism. The aim of the society was to push back against this threat, but this aim soon morphed into advocating for a return to the free market principles that had dominated during Capitalism 1.0.

Between 1950 and the mid-1970s, Capitalism 2.0 saw a period of unparalleled economic growth that has come to be known as the “golden age” of capitalism.

The economic boom, coupled with the scars that remained from the experience of the Great Depression, meant countries weren’t going to embrace the liberalisation of markets. The neoliberals knew this, but they were happy to bide their time.

As Kate Raworth explains in Doughnut Economics, With the backing of businesses and billionaires, they “funded university professorships and scholarships, and built an international network of ‘free market’ think tanks, including the American Enterprise Institute and the Cato Institute in Washington, DC, and the Institute of Economic Affairs in London.”

The good times were bound to come to an end at some point — that point came during the 1970s. Gripped by inflation and with levels of growth beginning to fall off, arguments for abandoning Keynesian economics became more compelling. By the end of the 1970s, the neoliberals saw their opportunity to strike.

Capitalism 3.0

Capitalism 2.0 did not come to an end due to an economic crash, but rather a rich elite used a period of inflation to their advantage to argue that a social reset was necessary to kickstart the economy.

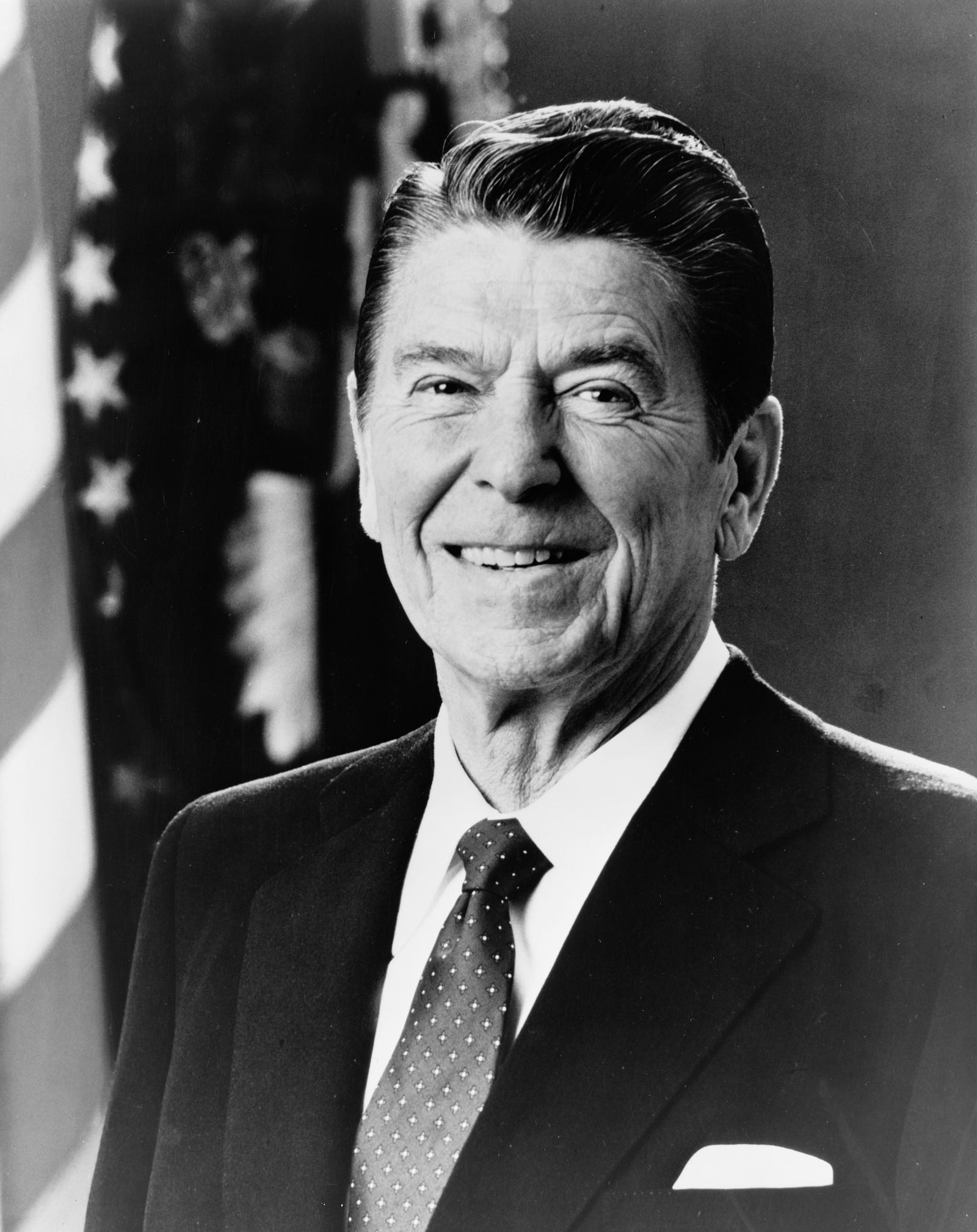

When Margaret Thatcher became British Prime Minister in 1979, followed closely by Ronald Reagan, who became US President in 1980 they surrounded themselves with Mont Pelerin members. Reagan’s election team included more than twenty members of the Society. Thatcher’s first Chancellor of the Exchequer, Geoffrey Howe, was also a member.

In The Lexus and The Olive Tree, Thomas Friedman describes how “Thatcher and Reagan “combined to strip huge chunks of economic decision-making power from the state…and from traditional Keynesian economics, and hand them over to the free market.”

The end of the Cold War combined with the Thatcher-Reagan heralded a shift to ‘Capitalism 3.0’ and the neoliberal ascendancy. Capitalism 3.0 has seen a return to the market fundamentalism that defined Capitalism 1.0.

Since the 1980s, the neoliberal belief that the free market would improve the quality of life for everyone quickly began to dominate most of the Western world. Underlying this belief is that if left alone, markets will produce efficient and fair social outcomes.

An economy fit for the 21st century

In reality, neoliberal policies have done the exact opposite of what was intended. As the graph shows in the US income inequality has become worse than when it peaked in 1928, the year before the stock market crash.

The graph provides a graphic representation of the impacts of the three phases of capitalism. Put simply, capitalism 1.0 and capitalism 3.0 led to increasing income inequality because that is what liberalism is designed to do. Capitalism 2.0 had the reverse effect, with the lowest levels of income inequality being experienced in the period 1940 to 1980. Again, it did so because that was what it was designed to do.

Inequality and poverty are not undesired outcomes. Poverty is by design and is the result of a greedy elite crafting the rules of the game that make them richer.

The graph is essentially a visual representation of why a social reset is required. What we need is an economy fit for the 21st century. What we need is an economy that provides for the needs of all within environmental limits. This does not mean a return to capitalism 2.0.

What we need is a much bigger social reset than that. Capitalism is an economic system that has had its day. It no longer serves its purpose. If anything, increasing production (which can only be achieved by using more of the natural world), is required to maintain capitalism (as it leads to economic growth).

This means capitalism works to destroy the environment we depend on to maintain thriving societies. So even if capitalism was achieving social harmony, it would still be leading to environmental disharmony.

We urgently need to move to a post-growth economy. An economy that seeks to increase well-being while decreasing our environmental impact. An economic system that is designed to meet people’s needs, rather than assuming increasing incomes will lead to increasing well-being. An economy that distributes the fruits of economic activity evenly, to ensure that it works for everyone, not just a rich elite.

We need a social and economic reset. But the last thing the rich elite who benefit so handsomely from the status quo want is change. And seeing as they own the media they have done a brilliant job in convincing everyone else that we all benefit from this state of affairs. They have captured the zeitgeist so overwhelmingly that the only way people will recognise the need for radical change is when neoliberalism unravels. Seeing as markets fail time and time again, it’s a matter of when, not if, the global economy crashes. When it does, calls for a social reset will become deafening.