We’re going to pay the price for turning the world into a giant farm

Supermarkets are stocked to the brim with thousands of exotic products. Takeaway services are delivered to your front door. Restaurants offer cuisines from every part of the world. When it comes to food choices we’ve never had it so good. But to feed eight billion people we’ve had to turn the Earth into a giant farm. By doing so we have inadvertently created a recipe for disaster.

The idea the Earth is a giant farm may feel like an exaggeration. It’s not like we’re being overrun by farm animals. And when we look at images of the Earth, we see vast forests that stretch beyond the horizon. We see awe-inspiring landscapes and angelic beaches.

What we don’t care to look at are the vast swathes of land that have been converted into farmland. We’ve become so detached from food production that we tend to disregard how food is produced.

Producing food happens to be one of our greatest strengths. We’re so good at it that we produce enough to feed ten billion people. That’s an incredible feat. One which owes itself to fertilisers. Fertilisers have greatly enhanced yields, hence why we can produce more food than we need.

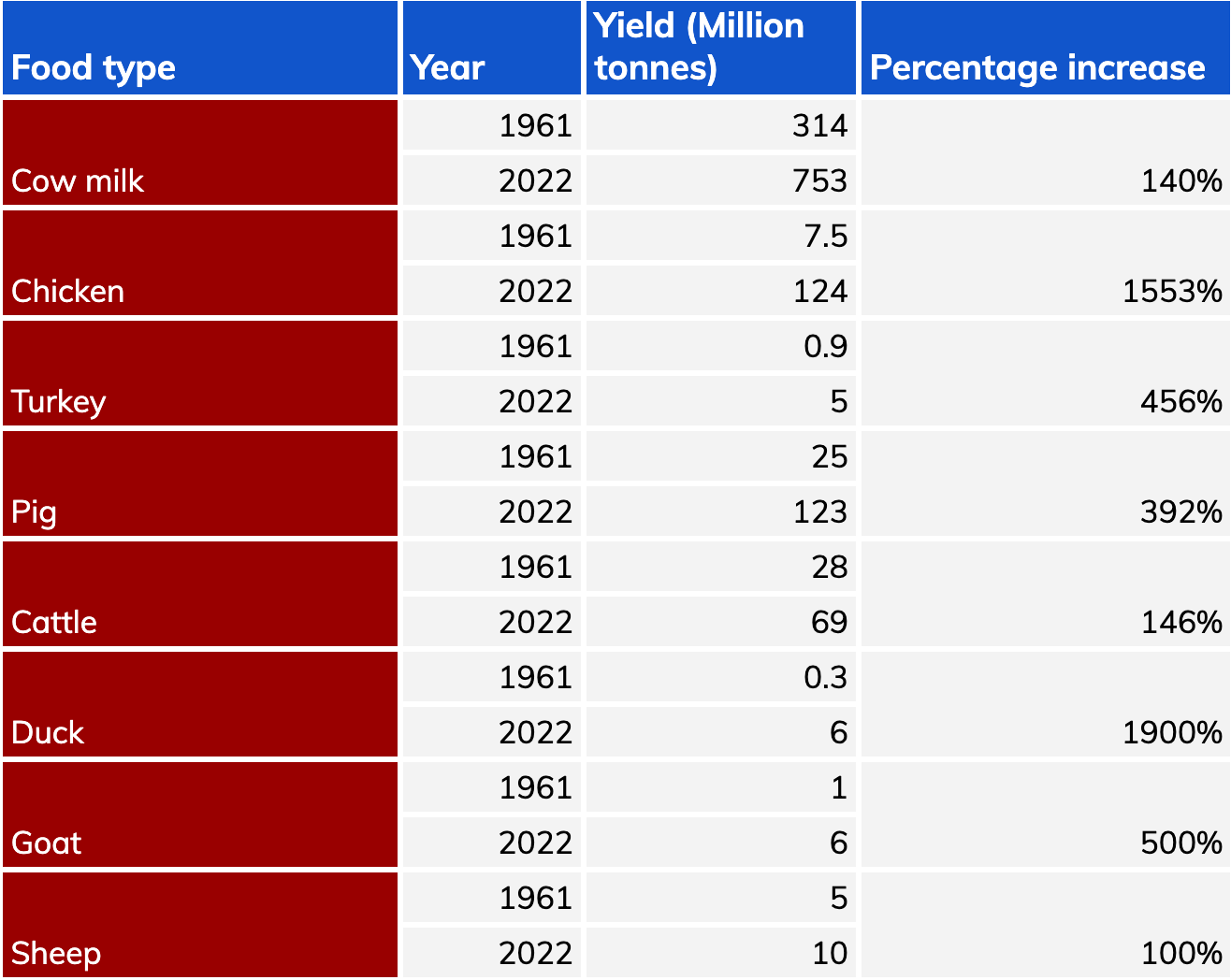

The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) data gives us a sense of just how transformative fertilisers have been when it comes to food production. The table compares yields and the area harvested for certain grains in 1961 (when the FAO began collecting data) and 2022.

Land-systems are the result of human interactions with the natural environment. Change in land-systems is driven primarily by agricultural expansion and intensification. While enhanced yields mean we produce more food on less land, the demands of a growing population keep on increasing. On top of this, rising incomes have changed dietary habits. The result is agricultural land use has increased sharply.

Livestock

Today half of all the habitable land on Earth is used for agriculture. While 23 per cent of that land is used to grow crops, 77 percent is used to produce meat and dairy.

Increasing incomes has made meat affordable to large sections of society. As a result, global meat consumption has increased dramatically. The FAO’s data for 1961 to 2022 shows beef production increased from just under 28 million tonnes to over 69 million tonnes. Pork went from 25 million tonnes to 123 million tonnes; chicken went from 7.5 million tonnes to 124 million tonnes.

That’s a lot of meat and producing it involves slaughtering 50 billion chickens, nearly 1.5 billion pigs and 300 million cows to meet the growing demand for meat.

Our farm of Earth-like proportions has started to come together. So what’s the issue with having turned the Earth into a farm?

It comes with disastrous environmental impacts. The agriculture sector, which includes farming machinery, rearing billions of animals, spraying fertilisers (made from nitrous oxide and phosphorus) and transporting food, leads to over 17 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions each year.

Rearing cattle is particularly destructive. São Félix do Xingu, an area the size of Ireland, is a municipality of Brazil in the heart of the Amazon rainforest. The area is home to a herd of cattle millions strong. As you can imagine, dense rainforest isn’t conducive to rearing cattle. So not only is the region one of the world’s biggest beef producers, it’s also known as the deforestation capital of the world.

Forest fires are often started intentionally to clear-cut the rainforest. When trees are burned they release carbon dioxide they once stored into the atmosphere. That rainforest is then replaced by cows that release methane through flatulence.

Not only that, but clear-cutting rainforest replaces a thriving habitat with a grassland, destroying biodiversity. As a result of deforestation, the Amazon has been pushed beyond a tipping point. The rainforest now releases more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than it absorbs. We have turned a precious ecosystem into a giant farm and a vital carbon sink into a carbon source, all to meet the demand for beef.

One giant farm

Just three percent of the world’s natural ecosystems, that is, ecosystems uninfluenced by humanity, remain intact. Nature documentaries create an impression that wild animals are abundant. But human interference with ecosystems has led to catastrophic declines in the populations of living species.

Predators are critical to healthy ecosystems, but since 1993, the population of African lions has reduced by 43 percent. Now, there are only 23,000 African lions left in the wild. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, the population of wild tigers has plummeted by 95 percent, 4,500 remain in the wild. Things aren’t much better in the ocean, which is estimated to have lost more than 90 percent of large predatory fish.

In 2016, only 7,000 cheetahs remained in the wild, and less than 5,000 Borneo and Sumatran Orangutans. The African Elephant is at risk of extinction by 2030 if current rates of poaching are maintained.

At least 1,829 out of 10,196 species of reptiles, that’s over 21 percent, are threatened with extinction. Overall, it’s estimated that out of seven to ten million species (the exact figure is unknown), one million are threatened with extinction in the near future. 40 percent of plants are considered endangered.

While numbers of wild animals plummet, farm animals are thriving. Livestock makes up 62% of the world’s mammal biomass; humans account for 34%; and wild mammals, just 4%. Farmed poultry today makes up 70% of all birds on the planet, with just 30% being wild.

Mass extinction

Humans represent just 0.01% of all living things. Yet since the dawn of civilisation, humanity has caused the loss of 83% of all wild mammals and half of plants.

Human activity has triggered the sixth mass extinction event. A mass extinction event is defined as a loss of 75 percent of all species on the planet over a geologically short interval — ‘short’ being below three million years.

While there have been five previous mass extinction events in the Earth’s long history, this is the first time a species is responsible for this cataclysmic event. And the pace of change is unprecedented. The sixth mass extinction event is taking hundreds of years, not millions. The rate of species loss we are seeing today is estimated to be 1,000 times higher than the ‘background’ or expected natural extinction rate.

Hollywood has tarnished our perception of environmental emergencies; it’s all about big explosions, destructive hurricanes, and catastrophic tsunamis. Nature doesn’t work that way. It changes slowly and often those changes aren’t perceivable.

Biodiversity may be collapsing, but it doesn’t feel like it is. While we take it for granted, biodiversity provides a range of services that are integral to human well-being, health, livelihoods, and survival. As the UNEP puts it;

“Biodiversity is essential for the processes that support all life on Earth, including humans. Without a wide range of animals, plants and microorganisms, we cannot have the healthy ecosystems that we rely on to provide us with the air we breathe and the food we eat. And people also value nature of itself.”

It receives far less attention than the climate crisis, but the health of biodiversity is just as important in maintaining healthy ecosystems. A team of scientists, led by the ecological economist Robert Constanza calculated the monetary value of all the goods and services provided by ecosystems.

In 1997, they came up with an estimated value of 33 trillion dollars, nearly twice the global production resulting from human activities at that time. It’s indicative of our relationship with nature that we have to put a price on it, that is, make it make sense from the market’s perspective, to get a sense of its value.

While our worldview drills the value of nature down to its role in production, if ecosystems begin breaking down, the precious, life-giving services they provide may well break down with it. We are potentially destroying the foundations on which human civilisation depends.

The farm must get bigger

Increasing demand for meat is increasing the intensity of the agricultural sector. As Johan Rockstrom puts it in A Safe Operating Space for Humanity, we may now be reaching a point where “further agricultural land expansion at a global scale may seriously threaten biodiversity and undermine regulatory capacities of the Earth System (by affecting the climate system and the hydrological cycle).”

To have any chance of turning the tide we must reduce the impacts of land-system change. The challenge is monumental when you consider the FAO estimates food production must increase by at least 60 percent to meet the demands of a population that is predicted to hit nearly ten billion people by 2050.

Agricultural practices are vital to creating a sustainable society because land-system change impacts the whole Earth system. What’s required is a radical transformation of agricultural practices. That transformation must be driven by our food choices. We must all start to eat locally and seasonally. Eating meat on a large scale has no place in a sustainable society.

The challenge is that we’ve all got rather used to the abundance of food choices that have come to define modern society. When it comes to meat, it’s not like people are being forced to eat it. They do so because it tastes good. It’s hard to get around that fact.

People won’t change when they see no need to change. Here’s the problem with being so detached from food production. But even if more people were attached to it, the vastness of the industry makes pressure points difficult to see. This is a problem with environmental changes generally. They are occurring on a global scale, which makes it seem that the changes aren’t occurring at all. Sure, we may read about the sixth mass extinction event, but it hardly feels cataclysmic.

Without experiencing the consequences of changes in our daily lives, being told something is happening just doesn’t create the required urgency or motivation for change. This is a problem with the psychology of global-scale environmental impacts generally. And so we remain locked into a food system that is hurtling us towards a future of chaos and unrest.

The current state of affairs can’t last. And due to our impacts on the environment, they won’t last. But a global epiphany seems unlikely. It feels inevitable that change will be triggered when we experience the consequences of our actions and we’re forced to do so. When chronic food shortages lead to an explosion in prices. When hunger and riots spread across the globe. That’s when things will change. Not now. Not when food shelves are stacked to the brim, and everything appears rosy.