Based on the law of cultural evolution, our fate appears inevitable

They can be easy to take for granted, but homo sapiens — that is, you and I — are an extraordinary species with extraordinary abilities. Our ability to form societies based around a shared understanding of highly complex nuanced cultures, our ability to understand the natural world and apply it through technology, our desire to push boundaries and improve human well-being. While extraordinary, these easy-to-take-for-granted qualities are a double-edged sword. Sure, they’ve culminated in a society that offers comforts (if you’re lucky enough to have a high income) that are incomprehensible to those who lived a few generations before, but those same abilities have come with terrible consequences. The desire to push boundaries, to build higher, to go faster, to want more, means we have influenced the environment around us to such a degree that we’re destroying the conditions we depend on to maintain thriving societies. The result is that we’re on the cusp of catastrophic environmental changes that have left us on the precipice of collapse. When looking at how cultures and societies have evolved, it appears the current state of affairs was inevitable.

The anthropologist Leslie White argues the more advanced a civilisation becomes, the greater its energy needs. White refers to this as the law of cultural evolution. Based on this law, a culture develops as it becomes more efficient at capturing energy and as the goods and services produced per unit of labour increase. It’s technological advancements that lead to a greater ability to increase energy capture, and so “social evolution is a consequence of technological evolution.”

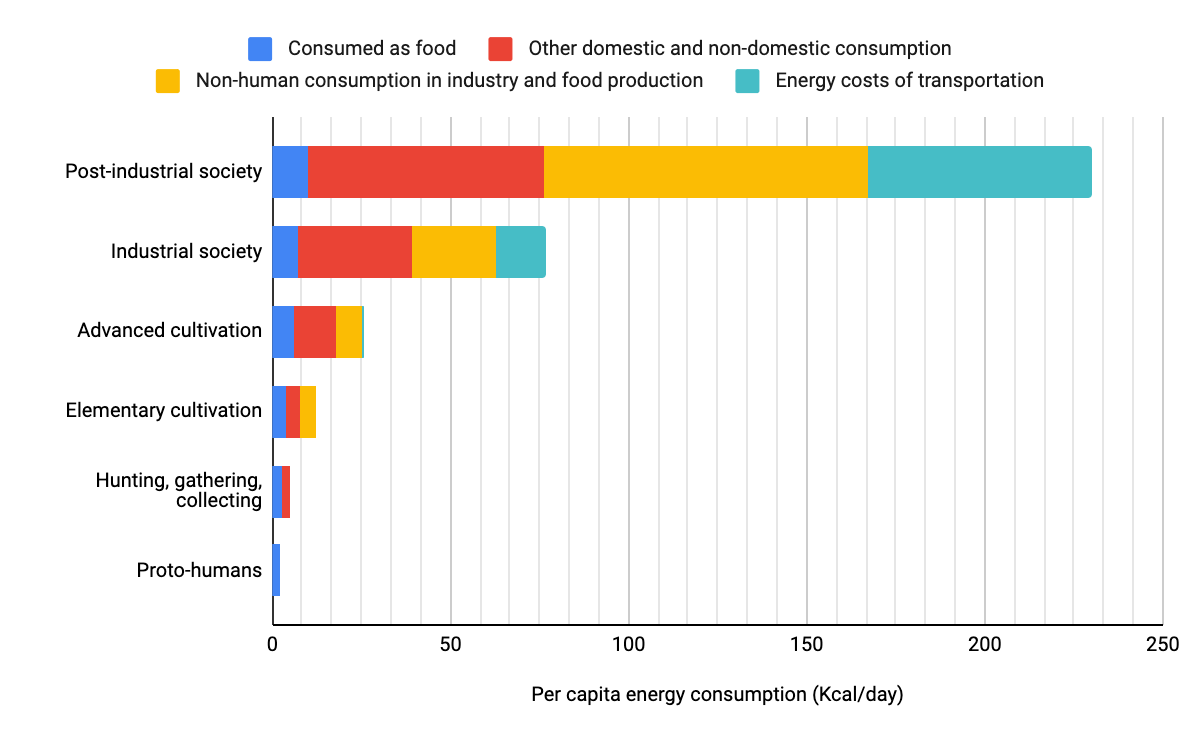

The graph below shows the relationship between cultural development, increasing technological sophistication and increasing energy demands. Pre-industrial societies revolved around a problem that has blighted humanity since time immemorial— getting enough food to eat. Thinking about the problem from the context of energy, in feudal societies (and other forms of subsistence preceding it), humans performed the work. Human labour was the energy source that tilled the soils, planted the seeds, and harvested the crop. It was a human-intensive process, which meant economic activity centred around making enough food for people to survive. Low technological sophistication equated to low energy demands.

The Industrial Revolution was driven by technological advancements that increased our ability to harness the energy stored in fossil fuels. Rather than humans performing the work, machines, driven by energy inputs from fossil fuels, do it for us. Now, machines toil the soils, plant the seeds, harvest the crops, and fertilisers protect crops from disease or pests, greatly enhancing yields. Increased technological sophistication equates to increasing energy demands. But it wasn’t until the Great Acceleration, triggered after the Second World War, that our energy demands went into overdrive. It is the utilisation of energy from fossil fuels that makes our time wildly different from anything in the human past.

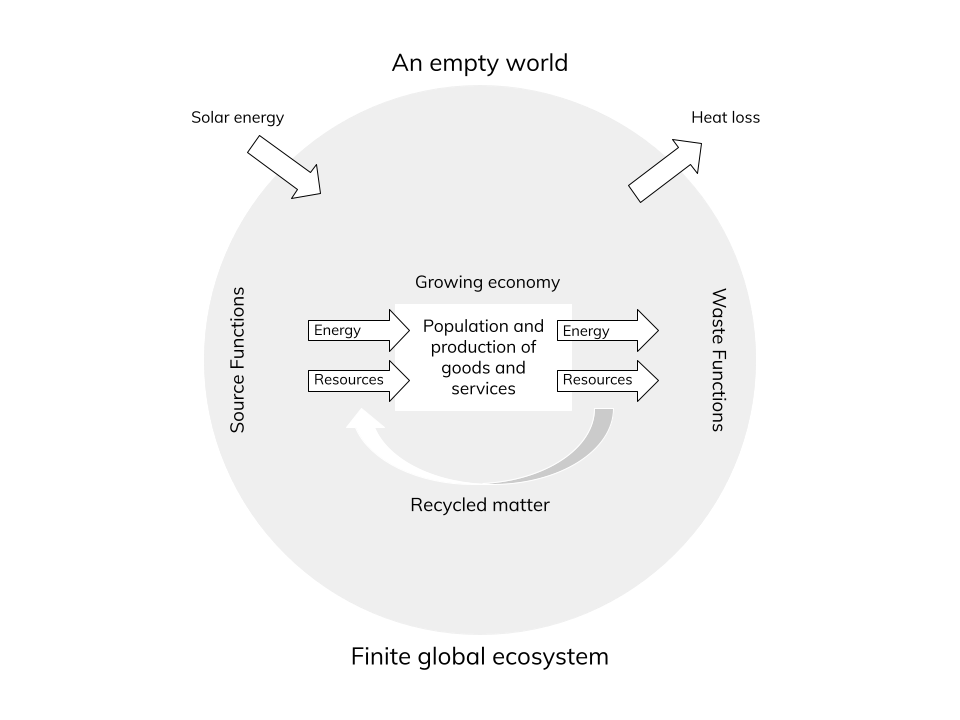

Fossil fuels created an energy bonanza, and over time we have become increasingly efficient at harnessing energy which has corresponded to an explosion in energy demands in post-industrial society. Our reliance on fossil fuels to sustain civilisation means that “85 percent of commercial energy, 65 percent of fibres, and most plastics are now produced from fossil fuels.” What’s apparent from the energy demands of different civilisations is that industrialisation marked a line in the sand in the human experience. This transformation has had radical implications. The image of an empty world shows the economy as a nested system within the natural world. As a closed system to matter, the material world around us is finite. But it’s an open system to energy, as shown by solar energy entering Earth, and exiting as heat.

The arrows moving into the economy represent sources of energy and resources used to make all the goods needed to sustain the population. The arrows moving out of the economy represent wastes exiting through sinks after they’ve been used. The four phases of this throughput of energy and resources are as follows;

- Take — resources and energy enter the economy as sources of economic activity.

- Make — energy is used to turn the resource into usable products or services.

- Use — the product or service is bought by people who use it.

- Dispose — products are thrown away and exit the economy through sinks.

Some of the energy and resources from economic activity get recycled as inputs, but most is processed in a linear way.

Pre-industrial society existed in an ‘empty’ world. At the time, “natural resources were abundant, social settlements were sparser, and inadequate access to infrastructure and consumer goods represented the main limit on improvements to human well-being.” This meant the material and energy inputs needed to provide for human needs were small relative to the large, but non-growing global ecosystem. In an empty world;

“It made sense to ignore relatively abundant ecosystem goods and services, and to favour the concentration of wealth in the hands of the few so that it could be invested and focus solely on increasing the consumption of market goods and services, which were relatively scarce. If wealth had to be concentrated in the hands of the few where it would be invested to fuel future growth, rather than distributed to the many where it would be consumed at the cost of growth, this was a sacrifice the present had to make for the future.”

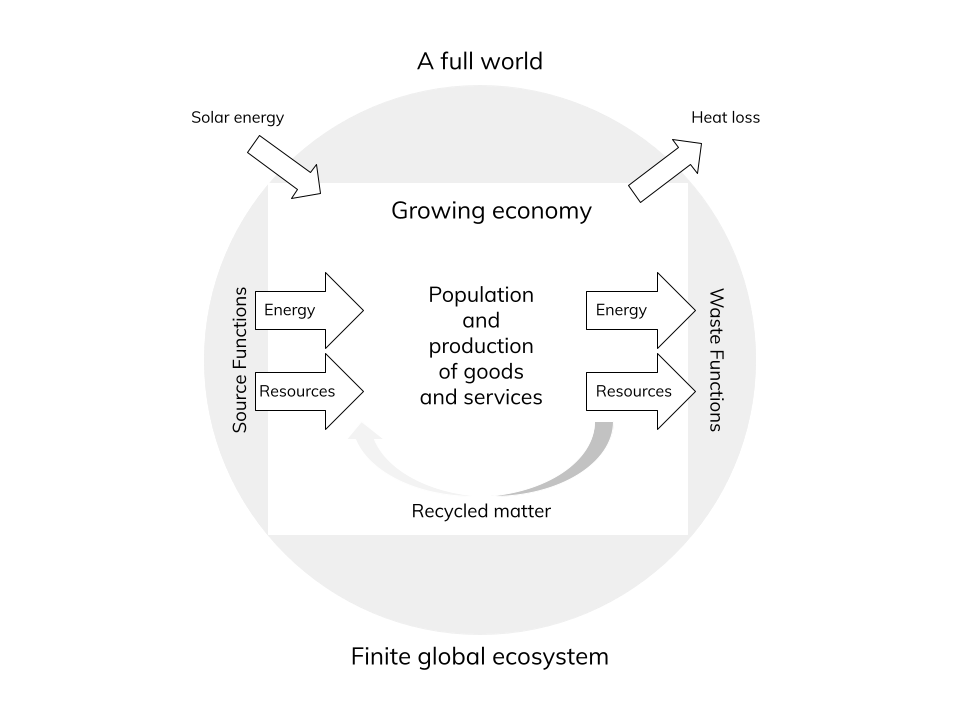

Modern society, and economic theory, developed in response to the environmental conditions that prevailed at the beginning of the industrial revolution. Environmental sources and sinks “were considered infinite relative to the demands of the economy.” This was a fair assumption to make at the time because the economy was small relative to the environment. But rapid economic expansion means that post-industrial society has created a ‘full’ world.

In a full world, a larger population needs greater amounts of energy and material inputs to support human needs. Now, the economy is large (and still growing) relative to the non-growing global ecosystem. While the scale of the economy has transformed beyond recognition, we remain locked into the same rules of the game that became established during the Industrial Revolution. The biologist Barry Commoner argues the modern economy is organised around very different principles to those that govern the natural world. For example, the linear processing of goods stands in direct contrast to the cycles governing the natural world. The water cycle, the nutrient cycle, the nitrogen cycle, and countless cycles help to maintain healthy ecosystems. The underlying function of every process is to conserve energy, not waste it.

Commoner argues there is a conflict between the two opposing worlds we inhabit. On the one hand, the environment is “cyclical, conservative, and self-consistent,” while on the other, the self-regulating market economy is “linear, innovative, but ecologically disharmonious.” The environmental crisis is a product of this conflict where profit maximisation in the economy is prioritised over environmental costs, which are externalised.

Since the Industrial Revolution, technology has been designed to maximise the throughput of energy and resources while minimising monetary and labour costs. Fossil fuels have become the dominant form of energy used by society because they are energy-dense and abundant. Those pros come with some rather nasty cons — they’re polluting and non-renewable. The result is that now, to sustain an economy of this size, we’re locked into using fossil fuels because while “the development of alternative energy sources is a priority, no currently feasible alternative can sustain the current rate of global economic growth.” Our dependence on fossil fuels is symptomatic of a decision-making process that revolves around self-serving interests. Decisions are made in isolation; the motivations of this reductionist approach are short-term economic gain, regardless of the long-term systems-wide impacts.

We have a tendency to point fingers, but what’s clear is no one has intentionally created the crisis we find ourselves in. It is the unintended consequence of a process of social evolution where the underlying motivation has been progress. That is, to make our lives better. It would be great if we could have all of the upsides of modern civilisation — high living standards — without any of the downsides — catastrophic environmental impacts — but life isn’t that simple, is it? The evolution of society has unintentionally locked us into a trap of our creation. Maintaining the lifestyles we have come to see as basic expectations requires a massive amount of energy. The bottom line is we either make sacrifices to living standards, or we refuse to accept the need to, which is a surefire way to drive us towards collapse. In a bitter irony, it would appear that our greatest strengths have turned into debilitating weaknesses, as ultimately, it is our strengths that have led us onto the path of mutual destruction.