Economists use the Environmental Kuznets Curve to justify economic growth in the face of increasing environmental pressures

There’s a consensus that sustainable development is a set of ideas that can allow us to deal with three crucial prongs simultaneously. Reduce environmental impacts, end poverty, and maintain a thriving economy. That third prong, maintaining a thriving economy, centres on the continued pursuit of economic growth. Even though the economy is so large we have exceeded the Earth’s carrying capacity and are in a state of ecological overshoot. Even though economic growth leads to increasing environmental impacts, like greenhouse gas emissions, and even though unlimited growth on a finite planet is impossible due to the pesky laws governing energy, growth isn’t seen as the problem that needs to be questioned; it is the solution to our problems.

Economists argue that its growth, surrounded by the bubble wrap of sustainable development, that will allow us to satisfy each of the three critical prongs. Economic growth is integral to invigorating economies that will lead to higher incomes and end poverty. Economic growth is essential to maintaining a healthy, thriving economy. Economic growth is essential to reducing the environmental impact of society. That third point seems highly questionable. Isn’t continued economic growth directly responsible for the climate crisis and the environmental impacts that have coincided with social prosperity? Well, yes, but indicators show that some environmental problems reduce with increasing incomes, for example, access to clean water and sanitation. Some get much worse — increasing incomes lead to rising consumption, creating an array of environmental impacts like greenhouse gas emissions, habitat destruction, biodiversity collapse, etc. Some problems get worse as economic development increases but improve as an economy matures, such as air quality and sewage pollution.

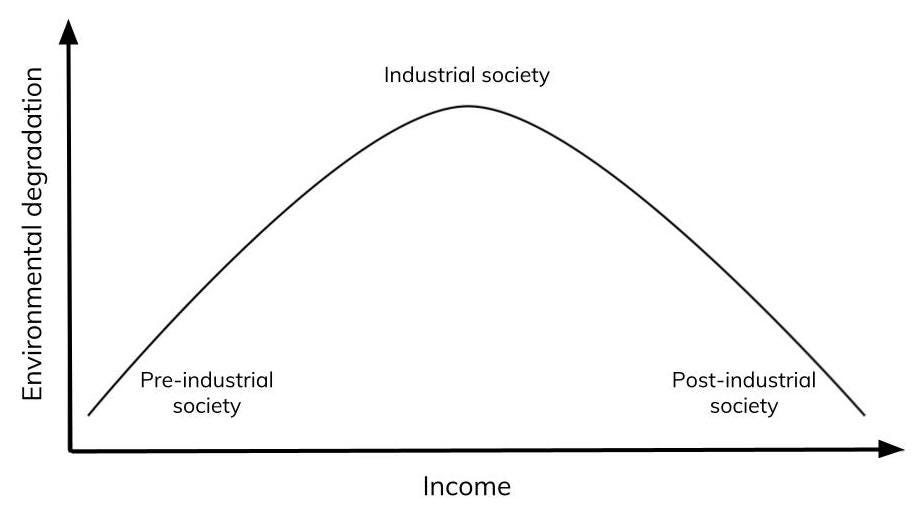

This third set of indicators has been latched onto by economists to show that for some environmental variables, the relationship between income and environmental degradation takes an inverted U-shaped form. As the graph shows, low incomes in pre-industrial societies equated to low environmental degradation. Industrialisation is accompanied by increasing incomes which sees environmental degradation rise. But as incomes continue to increase and society shifts into a post-industrial state, so does environmental concern, leading to policies that protect it. At the same time, preferences shift away from the most environmentally damaging goods and services. The graph has been dubbed the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) because of its similarity to the work of Simon Kuznets, who hypothesised that as an economy begins to develop, income inequality increases, but as the economy matures, it starts to decline as the benefits of economic growth begin to filter through society.

The statistical basis for the EKC is weak. Economic growth may improve some environmental indicators, but this doesn’t imply that “economic growth is sufficient to induce environmental improvement in general, nor that the environmental effects of growth may be ignored, nor, indeed, that the Earth’s resource base is capable of supporting indefinite economic growth.” On top of this, the EKC says nothing about how emissions reductions in a country are realised. For example “reductions in one pollutant in one country may involve increases in other pollutants in the same country or transfers of pollutants to other countries.” The EKC disguises the displacement of pollution across national borders because consumption in rich nations is driven by environmentally polluting production in poorer nations. International trade decreases pollution in developed countries while increasing environmental damage in developing ones. This trend supports the Netherlands fallacy, where developed nations like the Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark appear to be the essence of sustainability when they have just exported the environmental impacts of consumption that hide the fact their high living standards make them some of the most unsustainable countries in the world.

While it’s unclear why economic growth would spontaneously reduce a country’s environmental impact over time, ultimately, the reason doesn’t matter. The line of argument is made to help justify and defend the continuation of economic growth in the face of increasing environmental impacts. While some metrics, like air quality, have been shown to improve as an economy develops, it’s easy to cherry-pick improvements in isolation. When looking at the world economy as a whole, as it grows in size, it increases ecological overshoot, which places the environment under more pressure, not less. Whatever way you look at it, indefinite economic growth on a finite planet is simply incompatible with sustainable societies. But seeing as capitalism as an ideology depends on a belief in never-ending growth, it simply can’t be questioned. Question the unsustainability of economic growth, and you question every element of the economy that emanates from it. And so economists will do or say just about anything to justify the continuation of policies in support of growth, even when these are the very policies that are leading us towards catastrophe.