It all comes down to how wealth is distributed through society

IBM has paused hiring jobs that Artificial Intelligence (AI) could do. The software giant estimates AI like Chat GPT could replace 7,800 workers in the not-too-distant future. Great news for companies like IBM, who can slice costs while maintaining margins; not such great news for workers, as a host of sectors are set to be replaced by AI. It’s for this reason that Chat GPT is seen as a threat because it will take people’s jobs and livelihoods, but if we can create the same output without people having to work, surely AI replacing people in jobs should be a cause for celebration? In fact, AI could be a central component of a sustainable society, and yet it’s framed as some kind of malicious job killer that we should all fear. The fear is a product of how we conceive of social development and how wealth is distributed through society.

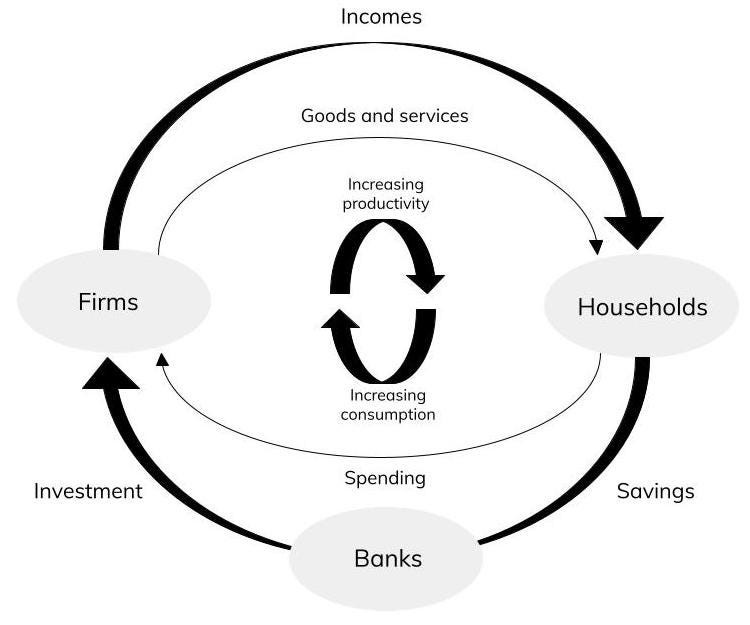

The circular flow of the economy illustrates the issue at hand. There are three protagonists involved in the circular flow of the economy — firms, households (comprising people) and banks. Their roles are as follows:

- Firms — invest in capital, like buildings and machinery, to produce the goods and services households want and need. Firms employ people from the labour force to make goods and services. Revenue from the sale of goods and services allows firms to pay employees income.

- Households — offer their labour to firms in exchange for income. People spend some of their income on consumer goods, while saving the rest in banks.

- Banks — use some of the savings from households to invest in firms.

As firms become more productive, they can sell more goods and services, increasing output. This leads to increased revenue. More revenue translates into higher incomes for households. Higher incomes mean households can spend more, increasing consumption. We buy goods and services that we value; otherwise, we wouldn’t buy them. We also wouldn’t buy stuff that isn’t improving our lives. This leads to a conclusion: continual income growth and, therefore, output growth, must be increasing social prosperity and human well-being. It’s for this reason that economic growth has become the core belief of modern society.

What this all means, then, is that ever-increasing production equates to higher incomes that leave society better off. The issue is that the circular flow of the economy exists in a void. It ignores the fact that throughputs of energy and resources used to make goods and services are scarce. It also assumes never-ending growth can go on forever. This is problematic for two reasons. First infinite growth on a finite planet is impossible due to the laws governing energy. Second, economic growth may have led to remarkable increases in living standards, but the economy has now become so large that we’ve exceeded the Earth’s carrying capacity. As a result, we’re in a state of ecological overshoot, which translates into undesired outcomes like greenhouse gas emissions, habitat destruction, and mountains of waste, which are changing the environmental conditions we depend on to maintain thriving societies. This never-ending increase in production and consumption is set to continue, which will only increase overshoot and make environmental impacts worse.

So what on earth does Chat GPT have to do with all this? Well, when you think about it, where does AI fit into the circular flow of the economy? The answer is simple, it doesn’t. If we were to find a fit for AI, it would be a worker (hence why it’s a job killer), which contributes to increasing productivity, and helps increase revenues. Obviously, AI doesn’t take home a wage, so the income that would have gone to a household ends up increasing revenue for the firm, which is why firms love AI so much. AI leads to higher profits for companies which get pocketed by a select group of well-paid executives and shareholders. The risk is that AI will lead to increasing inequality as an even greater proportion of economic growth is filtered into the hands of the richest.

If more and more jobs are being replaced by AI, then we’ll still be creating the same amount of wealth. The issue is that the mechanism used to distribute wealth through society in the form of employment and income will become increasingly unviable if entire sectors are replaced by AI. It has to be said, this mechanism of distribution doesn’t exactly work brilliantly at the moment. Rising inequality is a sign that a disproportionate amount of wealth is being filtered into the hands of the richest, while the poorest don’t make enough to make ends meet. What’s needed more than ever, is a different mechanism for distributing wealth.

The solution can be found in the form of a Universal Basic Income (UBI). A UBI guarantees each adult citizen a no strings attached monthly payment from the government. Rather than a trickle-up effect where the fruits of economic output are filtered to the hands of the few, a UBI distributes wealth across society. And it’s not like a UBI is some far-out utopian idea. In 2017, Finland carried out a two-year trial paying 2000 unemployed adults €560 ($635) a month. After two years, assessments showed no meaningful difference in job-finding rates among those receiving the payments compared to other unemployed workers. Those getting a UBI did report being happier, though. While it’s not possible to know the effects of a UBI if it were implemented nationwide, the Finns concluded that a restructuring of their welfare state would allow a UBI of €560 to be paid to each adult citizen, without raising taxes.

So long as economic growth remains the underlying goal of economies and social success is defined by being richer than everyone else, a shift to a UBI seems unlikely. What’s needed is to reimagine what social and economic success looks like. We need to develop a new conception of human flourishing based on sufficiency, moderation, frugality, and non-materialistic sources of meaning and satisfaction. This would not only help decrease inequality and help end poverty, but it would remove the necessity to keep on increasing production. The way we organise society could be radically different, and yet so long as we continue pursuing economic growth we will remain locked into a worldview that views AI as an enemy taking our jobs, rather than a great liberator that could free whole sections of society from work and create a tangible pathway to a sustainable society. If that potential doesn’t create the desire to transform how we do things, nothing will.