Consumption and sustainability are incompatible

The climate crisis is framed as a problem we must ‘solve’, assuming that technological innovation will allow us to overcome the challenge. But the climate crisis is an effect of emissions caused by human behaviour, a major cause of those emissions is consumption. Given the relationship between consumption and emissions, you would imagine there would be widespread calls to consume less—a global movement encouraging people to live lives of moderation. But the opposite is the case.

A jet-set lifestyle has become the archetypal symbol of success. This lifestyle glamorises excess. Jetting off to luxurious destinations, eating at the finest restaurants, driving the best cars, and wearing designer clothes. It’s considered an aspirational goal that people dream of achieving.

The issue with consumption is that every good and service we consume has a carbon footprint. The footprint of an item is the number of emissions created by producing (and using) it. This means the more stuff you buy, the larger your carbon footprint.

On the one hand, consumption is a symbol of a growing catastrophe; on the other hand, it symbolises social success. The challenge is made so difficult because this desire to consume has become normalised, to the point where if you don’t value a high-consumption lifestyle, you’re the one who gets questioned. And while rampant consumerism is a major reason emissions continue to increase, mainstream media isn’t encouraging people to consume less. In fact, less consumption is the last thing anyone wants because the economy’s health depends on people consuming more.

Economic growth is the goal that underlies all human activity. If economic growth is the economy’s engine, consumption is the fuel that feeds the growth machine.

Never-ending growth can only be sustained by rising consumption, which leads to higher emissions. This dynamic must be questioned, and yet there is an argument that more economic growth is needed to deal with the crisis.

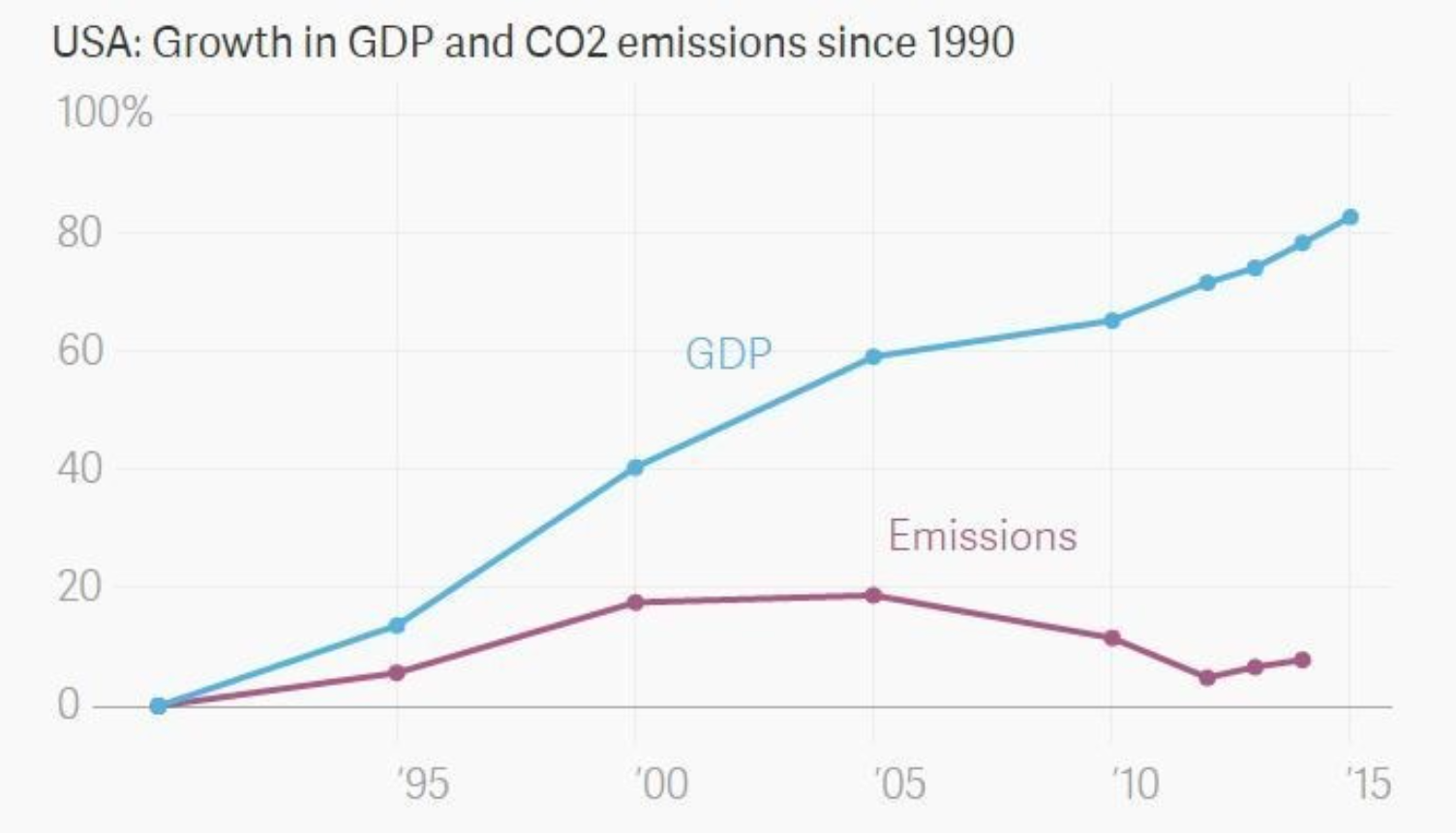

Technological innovation is considered a silver bullet that will allow humanity to overcome limitations and continue to prosper. Efficiencies will lead to a decoupling of production from emissions, meaning an economy can continue to grow without the undesired emissions that have historically accompanied that growth.

There has been some success in decoupling economic growth from emissions in advanced economies. As the graph below shows, since 1990, the economy’s carbon intensity has reduced as the US economy has grown. But due to the fact the economy has grown so much, in real terms, emissions are higher now than they have ever been.

On top of this, reductions in the energy intensity of advanced economies are being outweighed by the increasing energy intensity of developing countries.

With more and more counties following the same energy intense development process as developed nations, the Energy Information Administration (EIA) predicts global energy demands are set to increase by 50% in the next 30 years. While the EIA predicts renewables will make up 28% of energy consumption (from 18% today), 68% will still come from fossil fuels.

The solution behind the solution seems simple — the goal of an economy can’t be to grow. This is an issue with how we conceive of social development. Since the industrial revolution, economic growth has been the foundational goal of every industrialised nation. And the unprecedented levels of social development have resulted in an entrenched belief that any social problems can be solved through more economic growth.

More growth means more wealth, and more wealth means higher incomes. While its undeniable economic growth has led to miraculous increases in social development in many countries, over a billion people still live in poverty.

With one in eight people still living in poverty, calls for more economic growth seems justified. But poverty persists for such large sections of the population due to a lack of distribution—the richest 1% own nearly 46% of human wealth. More growth isn’t leading to more social development; it just makes the winners richer.

We’re all socialised to judge others based on their material wealth. That drives each person and motivates them to do more, want more and have more because having more than everyone else is a symbol of social success. But the underlying reason for this hive of activity is to create more wealth for companies and wealthy individuals who reap the benefits of all those people competing against one another to have the best stuff.

When countries are creating bold ambitions to become net-zero, a culture of consumption directly threatens that ambition. This is the central contradiction of our time. On the one hand, economic growth continues to drive all human activity, meaning everything is arranged around people consuming more, and inevitably society creates more emissions. On the other hand, we have a goal to reduce emissions. The two goals are incompatible.

So why isn’t growth and a culture of consumption being questioned and placed into the limelight as the symbol of the problem?

Because the wealthy elite doesn’t want to recognise this behaviour is inherently unsustainable. On top of this, people in developed countries would never accept the need to limit their lifestyle choices because it would feel like they’re making sacrifices.

To achieve net-zero, our norms, values and motivations must change radically. Our symbols of cultural success must be reorientated away from consumption and towards making positive social contributions. Away from selfishness and towards altruism. Away from greed and towards sharing.

If we don’t give up consumption, consumption will kill us. So we’re left with two paths. We either give up the addiction to stuff and move towards a path where each person lives within limits for the benefit of all. Or we continue celebrating consumerism as the symbol of social success. Seeing as there is a refusal to accept consumption is the problem, it looks like the path has already been chosen.