Necessity is the mother of invention

Unprecedented heat waves, biodiversity collapse, severe droughts and catastrophic flooding. That’s what the world is set to face if global temperatures increase by 4 °C by the end of the century. The risks of a warming planet are so severe many scientists believe social collapse is a real possibility. As the dangers we’re facing have become clearer calls for social transformation have become ever louder. The challenge is, how do you create such a transformation without destroying the integrity of society altogether? With the right incentives, such a social transformation is a real possibility.

Governments could make a game-changing intervention by implementing a carbon tax. A carbon tax would set a price on carbon by creating a tax on greenhouse gas emissions. The more emissions created by a product or service, the higher the rate of tax paid.

Baking the environmental cost within products or services helps to reveal the true cost of fossil fuels, making them uncompetitive against other energy sources with low or zero emissions.

High fossil fuel prices would lower demand, leading to decreasing supply — exactly what’s needed to achieve net-zero. Investors would also pull money out of fossil fuels in droves as it becomes increasingly clear they have no long term future in the world economy.

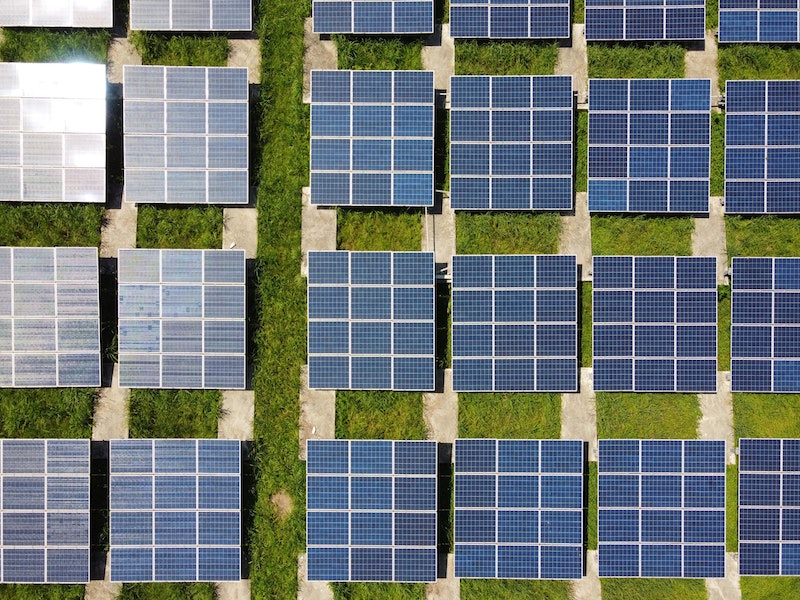

While a carbon tax would create a death spiral for the fossil fuel industry, cheap prices for renewables would encourage investment and send a clear signal that renewables are the energy sector’s future. And the more investment being directed towards renewables, the larger the sector would grow, increasing the attractiveness of further investment.

The potential impacts of a carbon tax show markets can instigate a transformation of the energy sector, but only if markets are regulated appropriately to ensure prices reflect environmental and social costs.

Current regulation is preventing such a transformation. In 2020 the IMF estimates fossil fuel subsidies amounted to $5.9 trillion and are expected to rise further over the coming years. Governments are enabling the fossil fuel industry by keeping prices artificially low. This incentivises continued investment into an industry that is undermining any chances of reaching net-zero by 2050.

There are reasons for this. Oil plays such an integral role in the economy that the oil price has a knock-on effect on everything else.

Rapid increases in social development that have resulted from industrialisation wouldn’t have been possible if it weren’t for this energy-dense wonder fuel. But our addiction to oil has made it so integral to everything we do that a quick phase-out is unlikely without massively destabilising the economy. As there is no ready-made alternative, it would hardly be sustainable to quickly wean ourselves off oil when doing so would have disastrous economic ramifications.

While this argument is valid, it seems worryingly shortsighted when you consider short term economic benefits are being prioritised over the long term health of the climate. But self-interested governments who desire to remain in power, are unlikely to take any radical steps that could hinder growth because doing so wouldn’t go down well with voters.

Another issue with a carbon tax is that any tax would need to be implemented globally. But nation-states aren’t set up to implement legislation on a global level. This is problematic when multinational companies operate globally. On top of this, some countries depend almost exclusively on fossil fuel revenues. So any such proposal would not only receive fierce pushback from powerful multinational corporations but from countries rich in oil, coal and natural gas reserves.

It’s not just fossil fuels where this is an issue. A system of national governments, and global companies, makes it difficult to properly regulate the market to encourage desired behaviour or innovations. Single-use plastics highlight the issue.

You might think if single-use plastic has such devastating environmental impacts, why isn’t it banned? Or more conservatively, why isn’t there a regulation that seeks to embed the environmental cost of producing single-use plastic into each item made?

Campaigners are calling for a ban on single-use plastics. In 2022, 117,000 people signed a petition to pressure the UK government to ban single-use plastics.

This is precisely the kind of regulation that could have a transformative impact. Coca Cola (and other drinks companies) justify the continued manufacture of single-use plastic on the basis that consumers like them. The real reason is that single-use plastic is a perfect material for their purposes. It’s durable, lightweight, non-reactive and most important of all, it’s cheap. Even if there wasn’t an outright ban and governments created a tax that accounted for the environmental destruction caused by single-use plastic, it would lead to an increase in price.

Now an argument against doing so could be that there is no ready-made alternative. But necessity is the mother of invention. Pricing single-use plastic out of the market would create the necessity that would mean producers of single-use plastic would have no choice but to innovate. At present, there is no such motivating force because companies can continue manufacturing them without any consequences.

Governments can create regulations that incentivise companies to innovate. But they persist in allowing companies far too much freedom to do what they want. While Coca-Cola has set a goal of producing half of their single-use plastic using recyclable materials by 2030, this still doesn’t resolve the problem of waste ending up in landfills and oceans. It just makes a bad problem, less bad.

A symbol of our focus on solving the effects of problems without questioning the causes is that technology is being created to clean up plastics from the ocean. While well-intended the cleanup effort can only do so much if the amount of single-use plastic waste continues to increase in the oceans.

The concept of the carbon footprint also illustrates the point. The idea of a carbon footprint is that by being aware of the emissions you cause as an individual, you can work to make changes and reduce your footprint. The small changes made by each individual can add up to significant reductions in carbon emissions.

Finding out your carbon footprint involves a carbon offsetting company asking you various questions about your lifestyle and spending habits. Based on this information, they calculate your footprint. You then pay a fee to the company to offset the emissions through an initiative such as planting trees in forests in developing countries.

What makes the carbon footprint a questionable concept from the get-go is that BP — an oil company — created it. They did so to help deflect attention away from oil companies and make individuals feel responsible for the problem. It was a brilliant PR campaign that quickly caught on.

Aside from it being created with ulterior motives, a major weakness of carbon offsetting initiatives is that if I’m paying a company to offset my emissions, what incentive do I have to reduce my footprint? The whole point of a carbon footprint is not just to offset your emissions but to make changes to your lifestyle to decrease your footprint. The problem is that the carbon offset market is isolated from prices in the wider market, which continue to encourage people to maintain carbon-intensive lifestyles.

In Freakonomics, the economists Stephen Dubner and Steven Levitt argue moral, social and financial incentives influence human behaviour. Incentives are a way to convince people to do more of a good thing and less of a bad thing.

If the right incentives can change behaviour, how might incentives help in reducing individual carbon footprints? Well, an element of achieving net-zero involves replacing shorter-haul air traffic by rapid rail. Short-haul flights, such as domestic flights, flights between European countries or between cities in the US result in the highest carbon footprint of any form of travel. Trains meanwhile produce one of the lowest footprints. A good way to decrease carbon footprints is to discourage people from flying short-haul and encourage them to use trains instead. But incentives aren’t encouraging a shift in behaviour.

Morally there is no campaign focusing on the negative environmental impacts of flying. If anything, we’re bombarded with adverts encouraging us to book short-haul flights.

The moral incentive is closely aligned with the social one. Going on multiple holidays a year is normalised. You’re more likely to be questioned for not going on holiday abroad than arguing you’d rather not fly to reduce your carbon footprint.

Perhaps the worst incentive of all is financial. Budget airlines often entice people to book short-haul flights for a few pounds. Flying is often far cheaper and quicker than other forms of transport, like trains.

Helping to keep the price of flying low is government subsidies. Airlines pay no tax on jet fuel in the UK, and there is no VAT charged on airline tickets. Like the price of oil, subsidies create artificially low prices that encourage people to book more flights — incentivising the exact opposite behaviour that needs to be encouraged.

There is an argument that airlines are simply meeting a demand. But people demand cheap, easy and quick access to a global transportation network. Currently, the only way that demand is met is by airlines, so there is no other choice but to fly. Cheap flights enabled by government subsidies lock us into an inherently unsustainable form of travel. And with incentives encouraging people to continue flying, there is no necessity to innovate and create a rapid rail network.

With the right regulations companies operating in markets could be incentivised to shift their business practices and trigger a transformation of how we do things. But at present governments sit on the sidelines, resistant to intervene in the market because powerful companies push back against change. With incentives encouraging the same behaviour, it’s little wonder emissions continue to increase and we continue to hurtle towards social collapse.