A growing economy is a healthy economy. The bigger an economy is, the more developed and better off society is as a result. These ideas lie at the heart of our economic structure. And it’s difficult to argue against the merits of growth as a driver of development.

The Industrial Revolution triggered a period of remarkable growth, that created never before seen social progress. In 1820, 90% of people lived in extreme poverty. By 2015 90% of people were free from extreme poverty.

In 1800, 12% of the population was literate, by 2016 that figure increased to over 86%. Every measurement shows economic growth leads to social development.

But once an economy reaches a certain level of development, it hits a tipping point. Beyond that point, growth doesn’t make society any more prosperous. The economist Richard Easterlin made this observation arguing:

“Between 1946 and 1970, the U.S. witnessed remarkable economic expansion. And yet surveys failed to show an upsurge in happiness throughout this period of post-war boom.”

Easterlrins findings came to be known as the Easterlin paradox. Arguments for why the Easterlin paradox occurs centre around wealth inequality. An economy may be growing, but if wealth isn’t distributed then the poor remain poor, and social prosperity stagnates.

Wealth creation isn’t the issue; it’s that wealth sticks to the wealthy. And oh my is wealth sticky. In the United States, the wealthiest o.1% own roughly 20% of the wealth. Globally, the wealthiest 26 people in the world have as much wealth as the poorest 3.8 billion people.

The aim of a growing economy

A redistribution of wealth could relieve the symptoms of the Easterlin paradox. But does the Easterlin paradox have a far simpler explanation? Namely, happiness has never been the underlying goal of a growing economy.

A growing economy aims to keep on growing. That doesn’t necessarily translate into a happier, more fulfilled society.

The arguments posited for the benefits of a growing economy never suggest happiness is the ultimate goal. A thriving economy is ‘the’ goal, which translates into a wealthier society. Whether that results in social satisfaction would be helpful, but it is not an end goal.

How we measure our economy reflects this. The predominant tool to measure the success of an economy is Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The GDP measures the productivity of a country’s economy. It provides a simple, visually appealing metric. If an economy has grown, GDP increases, that’s good. If an economy has shrunk, GDP decreases. That isn’t good.

But the number in and of itself tells you nothing about the state of society. As Robert Kennedy said, GDP “measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”

The issue with GDP is an issue with growth generally. If we’re focused on growth, where does this leave society? How can we be sure peoples needs are being met if this aim isn’t our underlying motivation?

If the happiness of people isn’t your ultimate goal, then growth may not lead to prosperity for society. But again, the issue with saying a ‘happy’ society is the underlying goal of an economy has its pitfalls. After all, happiness is subjective. My happiness is different from someone else’s happiness.

So can we create a concrete goal that is measurable and attainable? Something that an economy can aspire to achieve to create prosperity for all? And if so, can a growing economy help us achieve it?

The problem with growth

In thinking about whether a growing economy can help in creating prosperity for all, we need to reflect on the potential problems with a growing economy.

The publication of The Limits to Growth in 1972 was groundbreaking as it questioned the possibility of growth on a finite planet for the first time.

The books seismic conclusion was growth on a finite planet is impossible. The book predicted civilisation would collapse sometime in the 21st century as we start to come up against resource limits. The natural resources we depend on to sustain society being the ‘limits’ to growth.

As Kenneth Boulding once quipped “anyone who believes that exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.”

The impossibility of growth on a finite planet seems arbitrary. Yet, the Limits to Growth has been bombarded by criticism because it questioned the building blocks of our economy.

While many economists disputed the findings, nearly fifty years on the report is proving to be accurate. Our reliance on more means we’re starting to come up against limits.

An argument for change

And then there’s the small matter of the environmental impacts.

Environmental issues we’re witnessing today are a manifestation of the growth imperative. The climate crisis is a prime example. The crisis isn’t a problem in and of itself; it’s an effect of a problem. The cause is the dogma of growth. It is growth that underlies every business decision, every political policy, each person’s desires and motivations.

Our economy incentivises every one of us to behave in ways that result in an undesired outcome. The destruction of the environment we depend on to survive.

The fact economic growth doesn’t result in prosperity for all would be a solid argument for change. That growth is inducing environmental destruction leaves us with little choice in the matter. Our economy must change if we want to sustain civilisation.

An economy based on human needs

While redesigning our economy presents us with a monumental challenge, it also provides an opportunity to create an economy that provides prosperity for all.

In thinking about redesigning the economy, we need to consider, what does a person need to prosper?

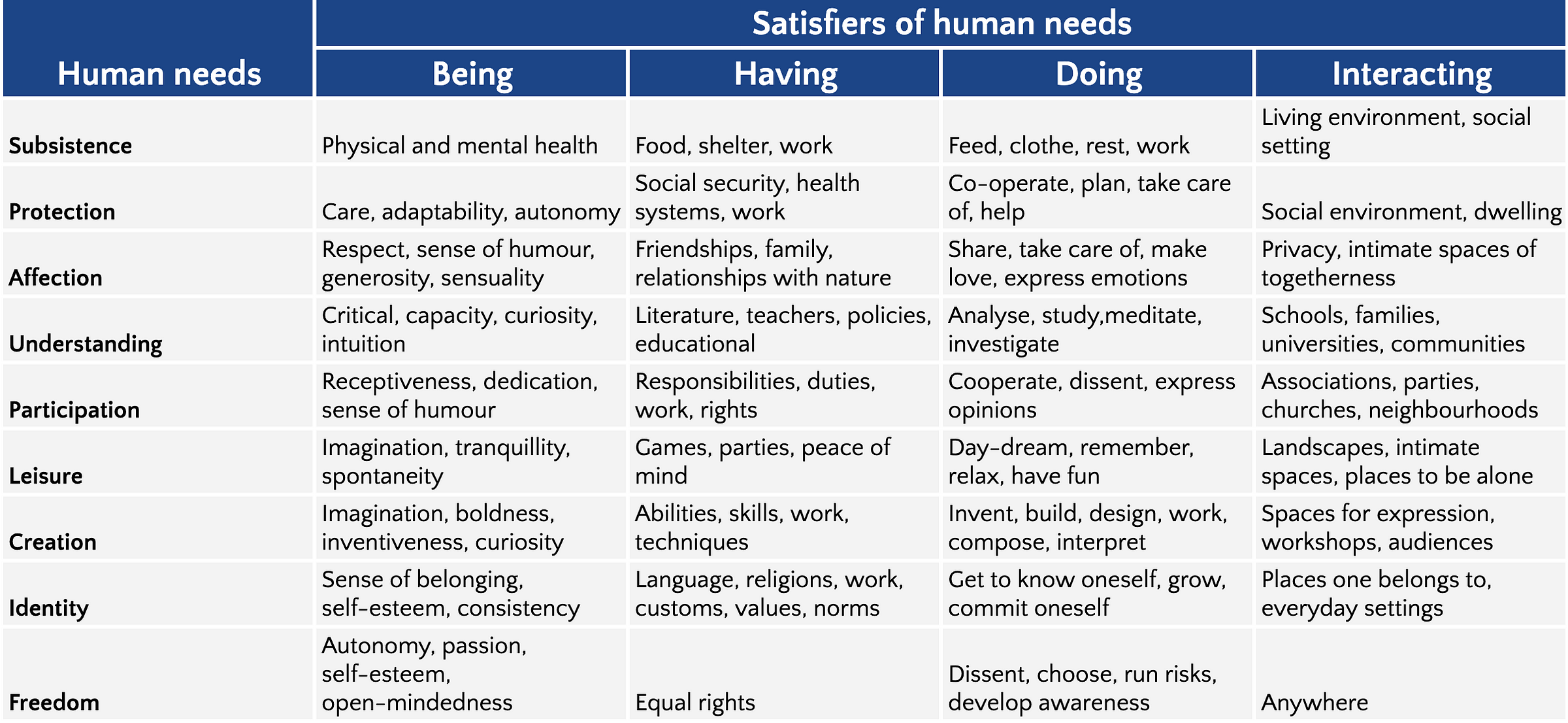

Manfred Max-Neef — the Chilean economists — work on fundamental needs aimed to answer that very question. Max-Neef argued that regardless of a culture or the historical time, everyone has the same needs (our fundamental human needs). The satisfiers of needs change over time. So human needs are constant and consistent. Satisfiers are fluid and reflective of cultural differences and the historical period.

Human needs are co-dependent and interrelated. Our needs then are a system, meaning to meet each need we must have the ability to meet all needs. There is also no hierarchy of needs, so each need is as critical as every other need, apart from the basic need for subsistence which is necessary for survival. If we don’t have food and water, we can’t hope to meet other needs as we’ll soon die!

A matrix of needs

Max-Neef suggests there are nine fundamental needs. Subsistence, protection, affection, understanding, participation, leisure, creation, identity and freedom. We satisfy our needs through one of four categories. Being (qualities), having (things), doing (actions) and interacting (settings). To give an example, we meet the need for subsistence by being physically healthy and by having food or shelter. Actions helping us meet the need include eating or resting. At the same time, the living environment (the setting) is fundamental for us to meet the need.

The matrix is in no way exhaustive; there are countless ways for us to meet our needs. But it does offer a visualisation of what we all need to live a fulfilling, prosperous life.

Satisfiers of needs have different characteristics. For example, pseudosatisfiers are satisfiers individuals believe will satisfy a need but end up doing the opposite.

Retail ‘therapy’ is an example. Advertisers entice you into believing buying lots of stuff meets the needs for leisure and identity, and up to a point, retail therapy does. But in our consumption fuelled society, you’re on a treadmill continually trying to keep up with the latest fashion. The pressure to keep up appearances can harm the need for identity, the very thing you were trying to satisfy in the first place.

Inhibiting satisfiers are when you satisfy a need, but doing so inhibits the possibility of meeting other needs. Watching lots of television satisfies the need for leisure. But watching tv obsessively undermines the need for understanding, creation and identity.

Likewise, synergistic satisfiers are ones where satisfying a need helps meet multiple needs. Breastfeeding satisfies the need for subsistence, while also stimulating the need for protection, identity and affection.

A needs-based economy

In a needs-based economy, instead of growth with no end goal, the economy has a specific vision. Taking a holistic view and creating a vision of what success looks like allows us to direct our economy towards this desired outcome.

The aim isn’t to create a utopia. If everyone has a platform to meet their needs, we won’t all be running around in a state of blissful happiness. Some people may have a platform to meet their needs but will still not be able to do so.

At present, the dogma of growth trickles down into every fabric of life. Transforming our economy into one that serves human needs would transform how society is arranged and with it our underlying motivations.

Changing the focus of governments

The government would play a crucial role in supporting society in meeting their needs.

Governments at present create policies that will win them votes. What we need are governments who are accountable for and designing policies supporting people’s needs.

Homelessness is an excellent example of how the role of government would transform. Based on GDP, the UK is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. And yet, there are an estimated 320,000 homeless people in the UK.

The government has the resources to deal with the problem, but homelessness exists because it’s not a priority for the government.

If a government were to make a bold claim they were ridding the country of homelessness and spending X amount to do so, it would be a controversial policy. Money better spent elsewhere.

Governments focusing on social problems

The reason solving homelessness could prove contentious is that our economy celebrates the individual. If you work hard, you’ll go far. If you can’t help yourself, why should the government help you?

Many people hold the view homelessness is the fault of the individual. They got themselves into that mess, so it’s their responsibility to get out of it. It’s certainly not the government’s problem.

But homelessness is a complex issue, which is a social failure, not an individual failure. As Gandhi said, “a nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members.”

So whose accountable for helping the homeless?

At the moment, the homeless rely on charity for support. I’ve always found the idea of charity odd. Not because charities aren’t brilliant at what they do. But because if there’s a charity, it means there’s an underlying problem the charity is trying to solve.

A charity existing is a symbol of the government failing to allocate the necessary funding to solve the problem. A problem that needs rectifying. Otherwise, there wouldn’t be a charity helping to solve the problem.

And yet, it’s left to charities (through the help of donations from people) to pick up the pieces. If there is a social problem, it should be the government’s responsibility to solve it.

Rather than governments focusing on creating policies that are good for the ballot box, we need governments focusing on what’s suitable for each person in society.

In a society prioritising human needs, poverty levels would be an essential measurement of failure. In particular, as the homeless are unable to meet their need for subsistence (in the form of shelter). A needs-based economy would incentivise governments to allocate resources to deal with the failure. Not relying on charities to help deal with social problems for them.

Changing the role of business

The role and relationship of business to society also needs a rethink.

Companies like Amazon generate huge profits, and Amazon’s business model has led it to become one of the worlds most valuable companies. The picture isn’t so rosy for Amazons employees, who are poorly paid and “treated like robots”.

From the perspective of the market, Amazon is a great investment. But none of the variables which make up whether a business is a ‘good’ investment depend on how well a company pays or treats its employees. So Amazon is excellent for making its shareholders money. But terrible for creating a platform for its employees to provide for their human needs.

Currently, employees are tools to maximise profits. What we need are businesses who value their employees as individuals, and support them in fulfilling their needs.

In a needs-based economy, a company like Amazon would be unable to function as it currently does. A needs-based economy would transform a business from an entity that seeks to maximise profit to one that supports employees to meet their needs.

In turn, the function of business would be to offer services or products that support human needs in society.

What’s good for the business should be good for society itself. Otherwise, what function does the company serve? To make a tiny minority of people richer? That goal seems absurd, and yet that’s our reality.

Changing the value of jobs

The job market would radically shift in a needs-based economy.

At present, your value depends on how much money you generate for your employer. In a perverse dynamic, we reward those we depend on the most the least. While rewarding those we rely on the least the most. This relationship seems irrational, but it’s normalised, and so goes unquestioned.

In a needs-based economy, value centres around how much you can contribute to helping people meet their needs. Meaning altruistic jobs with high social value; for example, doctors or nurses would be rewarded accordingly.

At present, we have a job market that rewards your ability to maximise revenue for companies. A needs-based economy would reward jobs that create needs-based value in society.

This shift in dynamic would revolutionise the job market, and help to entice the best minds to jobs creating the highest social value.

Changing people’s motivations

The dogma of growth has a pervasive influence on us as individuals. The goal of each person is to try and have as big a piece of the pie as possible. Regardless of whether that means others have to suffer for you to succeed.

A ‘dog eat dog’ mentality creates a competitive market where the only way to succeed is to prioritise your self-interests.

Rather than a winner takes all attitude to life. What we need are social cues that incentivise sharing between people.

An economy seeking to meet the needs of each person can transform the way we see the world and each other. Helping to dispel the toxic influence the self-interested individual has in society.

Aren’t people motivated by money?

Some people may argue humans are naturally selfish and greedy, and our economy is a manifestation of our natural inclinations.

So, in a needs-based system, what will motivate people?

Everyone wants to be successful. But ‘success’ isn’t some static end goal. What success looks like is socially constructed and changes over time. At present, the measurement of success is to be wealthy. And people’s incentives and motivations centre on achieving this goal. Those that do are ‘winners’, and feel successful when they compare themselves to others.

Measuring the success of society around the fulfilment of needs can have a powerful influence on peoples behaviour because metrics are powerful. “Human beings adjust behaviour based on the metrics they’re held against…what you measure is what you’ll get.”

If you measure success based on how much people earn, then the behaviour exhibited by people will be selfish and result in a rat race. By adjusting the measurements of success, you adjust what it means to be successful in society.

In a needs-based economy success centres on everyone helping everyone else meet their needs. And you could argue there is a selfish motivation for doing so. Assisting others to meet their needs enables you to meet your own needs.

What’s the point of it all?

If you’ve gotten anything from this article, I hope it’s that there are alternatives to our current way of doing things.

Because what is the point of doing anything if some people have to suffer as a result? Worse, on an individual level, our incentives result in behaviour that is destroying the environment we depend on for life. That isn’t so much counter-intuitive. It’s completely insane.

The issue we have is society is stuck in a fishbowl normalising the world around us. The world is and has always been, so what’s the big problem, right?

Some people may argue this is the best system we have. If the best we can do is create a system which compels our destruction, then we may as well give up now. But this view is the result of people being unable to see outside of the fishbowl. After all, never having tried to do things differently is no excuse not to try.

What has been clear for some time is the way we’re doing things isn’t working. But the wealthy elite who control our current system can only sustain their power by maintaining the status quo. Change risks affecting the status quo, so what incentive do they have to change?

It seems this elite has become mad with greed. The super-rich appears unperturbed by the environmental catastrophe we’re currently inducing. So blinded by greed, lust for power and a desire for more, it seems unlikely the economy is going to transform miraculously.

What is undeniable is the ideas and solutions to meet the challenges we face exist. What’s lacking is the will to change. Developing an economy based on human needs can offer a radical solution to our current plight. After all, if the economy works to grow, and not provide for the needs of society, then what’s the point of doing anything?