Nationalistic fervour is sweeping the US and Europe

In the last few years, the popularity of the far-right has surged. In Europe, seven countries—Italy, Finland, Slovakia, Hungary, Croatia, the Netherlands, and the Czech Republic—have hard-right parties in government. Far-right parties are becoming increasingly popular in Germany, the UK, Austria and France. Meanwhile, Donald Trump’s campaign to Make America Great Again has propelled him back into power in the US. So what’s with the far-right resurgence and what can the left do to reverse a worrying trend?

Driving the shift towards the far-right is an economic downturn in the US and Europe that has seen sharp decreases in living standards. In 2023 over 21% of the EU population was at risk of poverty. In the US, rising costs have turned basic conveniences into luxuries.

People are disillusioned with the status quo and want alternative solutions that provide hope for a better future. The new populist rhetoric adopted by far-right parties can be seen as a reaction, and naturally a solution, to economic recession.

These parties have pinpointed migrants, welfare scroungers, the homeless, the lazy, the unmotivated etc, as the causes of the economic downturn. The assumption is that should governments be tough on the causes they have identified then we’ll turn the tide, invigorate the economy and provide people with opportunity and a platform to make better lives for themselves.

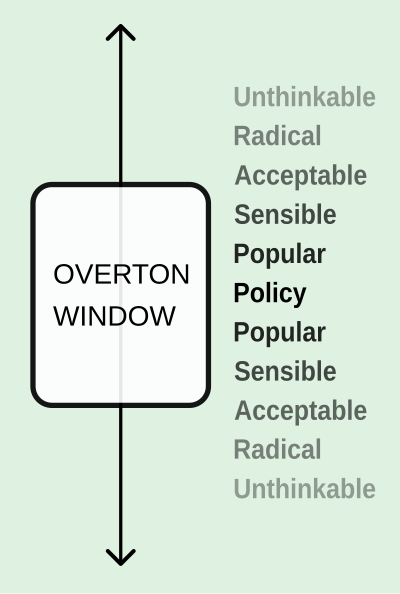

Rather than appearing radical and out of touch, these solutions, laced with intolerant, anti-establishment and nationalist rhetoric are hitting a nerve with voters. The Overton Window can help explain why.

The Overton Window

The Overton Window is named after the political analyst Joseph Overton who argued that the viability of political ideas is based on whether they fall within a window that defines political sentiments at that time. If a policy falls outside the window, it will be considered ‘radical’ or ‘unthinkable’. If it falls within the window it will be considered ‘sensible’ or ‘popular’.

The Overton Window shifts, expands, and narrows based on public sentiments at a given time. Since the early 1980s, ‘popular’ policies have revolved around neoliberalism, an ideology based on the assumption that free markets are good, and governments are bad. This assumption filters through to a belief that the smaller the government, and the less influence it has, the better, because the government is inefficient and incompetent.

This liberates markets and leads to better social outcomes because the market is efficient, innovative and productive. Liberalisation also liberates individuals and ensures a landscape which rewards the productive and punishes the lazy. An egalitarian haven, if you will, where you get back what you put in.

The crown jewel in the neoliberal scrapbook is the trickle-down effect. The idea is that taxing the rich less allows rich people to make investments that will stimulate economic growth, this will lead to higher incomes, and therefore, higher living standards for all. Hence, the idea that wealth ‘trickles’ through society.

The far-right has combined these assumptions, these ‘popular’ policies, with their nationalist, anti-establishment agenda. Importantly, because these assumptions are so ingrained the far-right isn’t a radical departure from where we are. The policy direction feels sensible and is indicative of an assumption about government incompetence on one hand and the effectiveness of the private sector on the other.

The Trump administration’s creation of the Department of Government Efficiency (Doge), led by Elon Musk, is a symbol of this attitude and disdain for government and the ‘establishment’. Making the government more efficient by slicing costs is in the spirit of being anti-establishment. While giving more power to private businesses to make more money for the individuals who own them (and the shareholders who invest in them), seemingly, isn’t.

The causes of decreasing living standards

This pattern is what makes the current shift to the far-right so alarming. Decreasing living standards and increasing poverty rates are not being caused by bloated governments, migrants, or welfare systems, but rather by neoliberalism itself.

It’s no coincidence that ever since neoliberalism has come to dominate policy in Europe and the US there has been a sharp increase in inequality. Take the trickle-down effect, funny enough, the impact of taxing the rich less is that the rich elite take a disproportionate amount of wealth generated by economic activity.

Meanwhile, governments have pursued austerity measures focused on making cuts to public services or the welfare system that are designed to ensure people don’t fall into poverty.

As Kate Pickett and Richard G. Wilkinson show in The Spirit Level, inequality erodes trust, increases anxiety and illness and encourages excessive consumption. Decreasing inequality helps to reduce all of these maladies and enhances social harmony, a feature of societies that are so desperately lacking at present.

It seems illogical that the solution to the problems caused by neoliberalism would be a more extreme version of neoliberalism, but that’s what makes new populism so dangerous. These self-serving individuals don’t care about society. They care about maintaining a landscape that is conducive to enhancing the ability of the rich to get even richer.

This is exemplified by Trump’s plans to slash the corporate tax rate to 15%, helping to reinforce the causes of poverty and decreasing living standards he claims to be solving.

Bad for business

So what of the left in all of this? An element of new populism that offers an insight into why the far right is gaining traction is its approach to the environment.

Parties on the right are less likely to favour environmental protection. They tend to argue environmental policies are bad for business, risking jobs and economic performance.

Left-wing parties tend to support environmental policies, arguing that only by embracing a green approach can we mitigate against the worst impacts of the climate crisis. Doing so can help stimulate jobs in new markets and industries and create an economy that is fit for purpose.

Weaponising environmentalism has created a debate where there should never have been one. Analysis by Deloitte shows that if we do nothing about the climate crisis, the damage could amount to $178 trillion in costs by 2070. Meanwhile, a rapid transition to a low-carbon economy could see a $43 trillion gain for the global economy.

While the evidence suggests inaction will have catastrophic economic impacts, right-wing parties, with support from vested interests, cling to the argument that being green is ‘bad for business’ because it suits their agenda and self-interests.

In fact, Trump denies climate change altogether. And this reinforces the anti-establishment sentiments that have come to define the new populist movement.

A lack of identity

The idea government intervention to protect the environment is bad for business is symptomatic of the problems afflicting the left generally. The Overton Window has shifted so far to the right that leftist solutions centred on bigger government and greater regulation seem radical, out of touch and detrimental to the economy.

Compounding the issue is that the left is facing an identity crisis. It’s not entirely clear what the left stands for or how alternative policies will work for the greater good. But within the left lies thinking that does offer hope. Post-growth economic ideas revolve around the fact that to achieve sustainable societies we must abandon economic growth as the underlying goal of the economy.

This is because growth demands greater inputs of resources and energy to achieve greater levels of output, facilitated by increasing consumoption. An outcome of growth is increasing environmental pressure points, which translates into increasing greenhouse gas emissions, increasing habitat destruction and biodiversity collapse.

In Managing Without Growth, Peter Victor argues the challenge with advocating a post-growth economy is that:

“the scope of change required for managing without growth is so great that no democratically elected government could implement the requisite policies without the broad-based consent of the electorate. Even talking about them could make a politician unelectable.”

Recognition of the need to move beyond growth isn’t mainstream, it’s also difficult to argue why we need to move towards a post-growth economy in populist soundbites that will be attractive, easily understood, and compelling to attract voters. So for now, the left is devoid of viable solutions to economic and social challenges.

Such is the success of the right in capturing the zeitgeist the only way people will be convinced of an alternative direction is through an economic crash. If the economy crashes it will expose neoliberalism for what it is, an ideology designed to benefit the few at the expense of the many.

2024 exceeded 1.5C for the first time (making it the hottest year on record). We have crossed a threshold scientists had long warned would signal a shift into a world of dangerous climate change. Now we have crossed the threshold the required crash doesn’t appear far off.

As we progress into the twenty-first century the climate crisis is going to increasingly feel like one. The crisis will translate into weather extremes, an example is an increased risk of global droughts that will lead to food (and water) shortages, triggering sharp price spikes.

Shortages will lead to constraints on what people can buy. This will not only exacerbate issues with inequality and living standards but it will make it harder for governments to maintain economic growth. Should we be unable to maintain growth, a global depression will set in.

With unrest, uncertainity and shortages, the spectre of war will hang on the horizon as countries fight over scarce resources. Crucially, once living standards are decreasing and it becomes abundantly clear that the cause is a changing climate, that’s when calls for a post-growth economy will become more compelling.

It’s in that environment where post-growth ideas have an opportunity to thrive. The obvious risk is that a time of extremes could create a breeding ground for fascism and see a lurch even further to the right. The left has a duty, for all kinds of reasons, to build sustainable societies that work for all. The preparations that are made now will determine whether it is successful when conditions allow for a shift in the Overton Window. If it does, then we just might be able to forge a new society built on shared prosperity.