The commodification of the climate crisis is leading to questionable results

Carbon markets have exploded in the last few years. Carbon credits work like permission slips for emissions. When a company buys a carbon credit, they gain permission to generate one tonne of CO2 emissions. When a company removes a tonne of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, it can generate a carbon offset. Other companies can then purchase that carbon offset to reduce their carbon footprint. The idea is that carbon markets can reduce greenhouse gas emissions in a cost-effective way. But, how effective is the market in reducing emissions?

In theory, carbon markets could help decrease emissions without impacting economic activity — which has proven a major obstacle inhibiting tangible climate solutions. That’s a clear benefit of creating a market. By doing so you place a price on carbon as if it were a commodity. This may seem like an odd ‘benefit’ but it helps to translate the problem into the language of capitalism.

The fact the carbon market is set to be worth an estimated $100 billion by 2030, hints at its growing influence. Another benefit is that money generated from the market can help to fund climate projects, often in the developing world. These projects work as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives as companies can offset emissions by supporting development projects. At the same time, communities in developing nations benefit from the investment.

It all sounds wonderful at face value, but in practice, the growing value of carbon markets points to the fact the motivation is more about making money out of the climate crisis, than creating tangible solutions to overcome it. The market also happens to be fraught with issues, for starters, it’s difficult to purchase carbon credits, so buyers will often go through brokers who act as middlemen to identify and buy credits. The market is also unregulated so revenue that should be directed towards climate projects ends up remaining in brokers’ pockets.

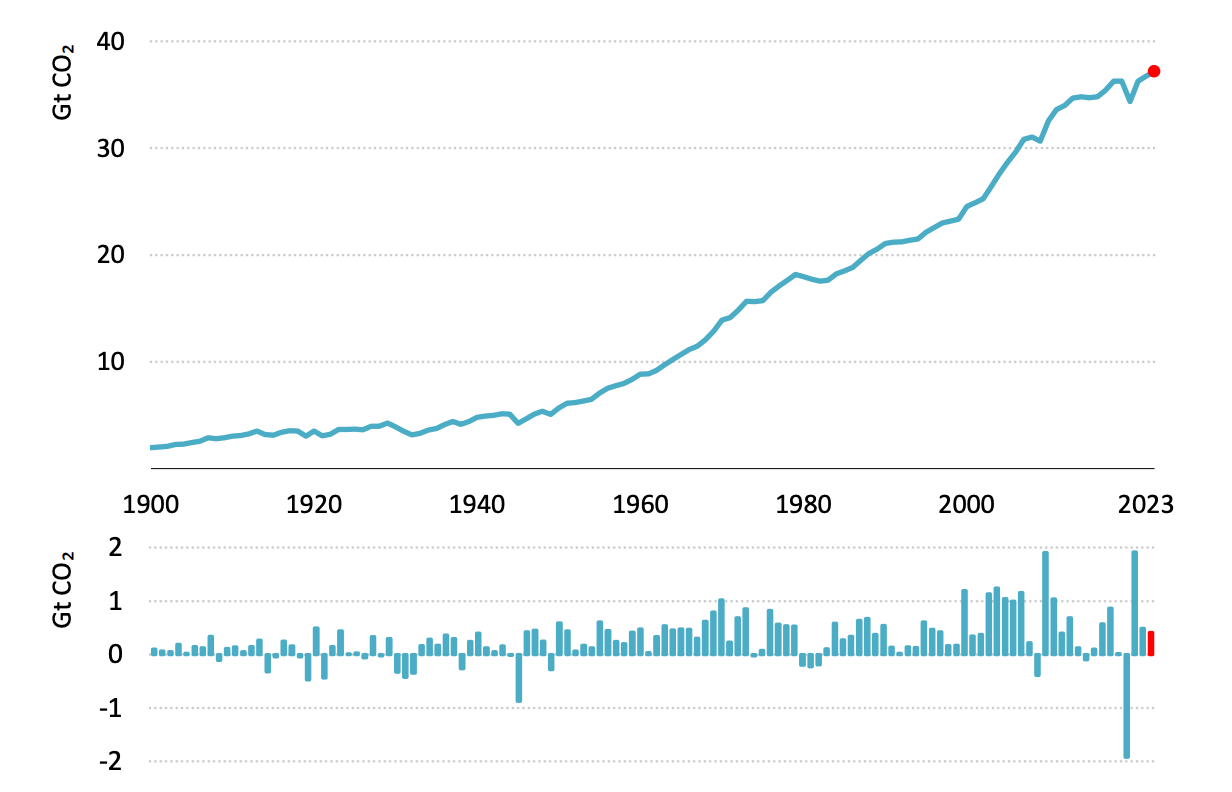

Whether emission decrease is ultimately our barometer of success so if people are making money from carbon markets it wouldn’t be such a bad thing if the market helped to reduce emissions. But as the graph shows, emissions continue to rise, reaching a record 37.4 billion tonnes in 2023.

What’s clear from the graph is that it’s not just carbon markets that are failing, emissions continue to increase in the face of millions of different initiatives from governments, businesses, NGOs, universities and communities. So why do emissions continue to increase in the face of so many efforts to decrease emissions?

Accounting for failure

The problem with the carbon credit market is symptomatic of an underlying problem with how we are trying to reduce global emissions. In a capitalist system, any solution to the climate crisis must be commoditised because it won’t ‘work’ unless it can be sold and have some kind of economic value.

This is the issue with how we’re dealing with the climate crisis generally. Capitalism sets the rules and constrains what is possible and what is not. If the solution isn’t cost-effective, if it can’t be sold, or if it undermines the health of the economy, then it’s not considered a solution. Even if its impact would dramatically decrease emissions, the consequences of the solution mean it would never be implemented because it would be considered economically unviable.

The fact that economic considerations always take precedence is indicative of our approach to solving the crisis in general. Take carbon footprints, which work in tandem with carbon offsets. The idea is that if you are aware of the emissions you cause, you can work to make changes to reduce your footprint. The small changes made by lots of individuals can add up to significant reductions in carbon emissions.

Carbon offsetting companies facilitate the process. They calculate your footprint based on various answers to questions about your lifestyle and spending habits. You then pay a fee to the company to offset the emissions through climate projects. The concept is questionable from the get-go because BP — an oil company — created it. They did so to make individuals feel responsible for the problem. It was a brilliant PR campaign that quickly caught on.

Aside from being created with ulterior motives, the whole point of a carbon footprint is not just to offset emissions, but to decrease your footprint. Carbon offsets don’t create the right incentives to change behaviour.

In Freakonomics, the economists Stephen Dubner and Steven Levitt argue moral, social and financial incentives influence human behaviour. Incentives are a way to convince people to do more of a good thing and less of a bad thing. Reductions in smoking levels in the UK show how effective incentives can be when these incentives are combined.

The moral incentive to stop smoking has been well-known for decades, it’s terrible for your health. Advertising campaigns, using shock tactics to communicate how bad smoking is, do a great job reinforcing its effects on health.

There was a time when smoking was considered good for you. Socially, the act of smoking was normalised and easily accessible, even, almost incomprehensibly, on planes. Now, laws work to ostracise smokers, for example, smokers have designated smoking areas. In shops and supermarkets, cigarettes are hidden out of sight, adding to the social stigma associated with smoking. These laws create a social incentive to stop. Then there’s the financial incentive. An average pack of cigarettes is £12.64. 80 per cent of the price is tax, making cigarettes an expensive habit worth giving up.

A combination of the three incentives led to a five per cent reduction in smokers between 2011 and 2018. But the change could only happen with effective government policies designed to incentivise people to stop smoking.

The right incentives

An effective way to decrease carbon footprints is to discourage people from flying short-haul and encourage them to use trains instead. But incentives aren’t encouraging a shift in behaviour.

Morally there is no campaign focusing on the negative environmental impacts of flying. If anything, adverts encourage us to book short-haul flights. The moral incentive is closely aligned with the social one. Going on multiple holidays a year is normalised. You’re more likely to be questioned for not going on holiday abroad than arguing you’d rather not fly to reduce your carbon footprint. Perhaps the worst incentive of all is financial. Airlines pay no tax on jet fuel in the UK, and no VAT is charged on airline tickets, helping to make flying far cheaper than other forms of transport, like trains.

There is an argument that airlines are meeting a demand. But people demand cheap, easy and quick access to a global transportation network. Currently, the only way that demand is met is by airlines, so there is no other choice but to fly. Cheap flights enabled by government subsidies lock in an inherently unsustainable form of travel. And with incentives encouraging people to continue flying, there is no necessity to innovate and create a rapid rail network.

Without seeking to incentivise behavioural changes, any positive impact of carbon offsets is limited. Exacerbating the issue is that governments and companies want you to consume and lead a carbon-intensive lifestyle because doing so helps to invigorate the economy and increase GDP.

A carbon tax

A global carbon tax could create the right incentives that support transformative change. A carbon tax sets a price on greenhouse gas emissions, ensuring the price of emissions is baked into products and services. This helps to reveal their true cost.

Doing so would send fossil fuel prices spiralling upwards, which would lower demand. This would see investors turn their back on fossil fuels as it becomes increasingly clear they have no long-term future in the world economy. At the same time, renewables would become far more competitive, helping to increase demand. Increasing demand would attract investment, enabling further growth of the sector.

The potential impacts of a carbon tax show markets can instigate transformative change, but only when they are regulated to ensure prices reflect environmental and social costs. Current regulation is doing the exact opposite.

The IMF estimates that fossil fuel subsidies amounted to $5.9 trillion in 2020, and they’re expected to rise further over the coming years. Governments are enabling the fossil fuel industry by keeping prices artificially low, but there are reasons for this. As the lifeblood of the economy, the price of oil has a knock-on effect on everything else, so a cheap oil price is vital for price stability.

That the global economy depends on cheap oil is an unintended consequence of the evolution of modern society. Rapid increases in social development accompanying industrialisation wouldn’t have been possible without this energy-dense wonder fuel. As there is no ready-made alternative, a quick phase-out of oil is hardly sustainable when it would have disastrous economic ramifications.

The argument, while valid, is worryingly shortsighted when you consider short-term economic benefits are being prioritised over the long-term health of the environment. It’s also understandable when self-serving governments are motivated to remain in power, so they’re unlikely to push for a carbon tax when doing so would hinder economic growth, a surefire way to be booted out of office.

On top of this, some countries depend almost exclusively on fossil fuel revenues. So any concerted effort to introduce a carbon tax would not only receive fierce pushback from powerful oil companies but from countries rich in oil, coal and natural gas reserves.

Not fit for purpose

27 countries have implemented a carbon tax on a national level, including the European Union (comprising the 27 member states), Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and the UK, with varying levels of success. This is a step in the right direction, but the fact that carbon taxes have been implemented nationally reveals a fundamental flaw in our approach to dealing with the climate crisis.

The climate doesn’t have borders, but we’re trying to solve the problem by slicing it up into parts and leaving it to respective countries to deal with. Nation states aren’t in it for everyone; they are inherently self-interested and will always seek to do what’s in their own best interests. When it comes to reducing emissions, the optimal strategy would be to emit freely and free-ride on the carbon controls of other countries.

The nation-state is a system of governance that has worked for hundreds of years, but this organising principle starts to break down when dealing with global problems that require a coordinated, unified response. As argued in Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene, what’s needed is a “fundamental reorientation and restructuring of national and international institutions toward more effective governance at the Earth System level, with a much stronger emphasis on planetary concerns in economic governance, global trade, investments and finance, and technological development.”

With this in mind, a logical approach to deal with the climate crisis would be to mirror the Earth system and create a global government which establishes a vision of sustainability. We can then create a strategy that manoeuvres us towards that vision of success, with each region taking responsibility for implementing actions that move us towards the vision.

But as Dani Rodrik argues in The Globalisation Paradox, calls for a global government “is a fool’s errand, both because national governments are unlikely to cede significant control to transnational institutions and because harmonising rules would not benefit societies with diverse needs and preferences.”

There is also the small matter that love for one’s country, and the patriotism it inspires is encouraged. It provides people with identity and a sense of pride. It’s naive to imagine that governments would give up their autonomy or that citizens of those countries would accept any such decision. So the nation-state goes unquestioned, and we continue to deal with a problem we’re not set up to deal with.

Rather than creating the right incentives for innovation, we’ve commoditised the climate crisis and created opportunities to profit from the problem. These actions serve a vital purpose by helping to justify the continuation of business as usual. In that sense, current climate solutions do more harm than good. What’s required is an awareness that tangible climate solutions involve transformative social change.

Without a radical shift in perspective, acknowledgement of the need for such transformative change seems unlikely. What does seem likely is that people will continue to find opportunities to monetise the problem, emissions will continue to increase, and society will continue to hurtle towards a crisis of unimaginable proportions.