The risk of climate and societal breakdown is finely balanced against the opportunity to redesign society from the ashes.

The most dangerous thing about climate change is that we decided to refer to it as climate change. It doesn’t create a sense of urgency — there doesn’t seem to be any danger from some ‘changes’. Change is, after all, a constant in life. Look beneath the surface, however, and rapid climate change is a sign of imminent social collapse.

Inevitably, the spectre of collapse comes with some terrifying risks. But these are balanced against some tantalising opportunities.

We arrogantly assume that our technologically advanced civilisation is somehow different from those preceding it. In the Fate of Empires, John Bagot Glubb shows how history has followed a pattern over the last 4,000 years: virtually all previous civilisations have suffered collapse, regardless of their size or complexity. So, why is modern civilisation on the cusp of suffering a similar fate? And what can we learn from those that came (and went) before us?

Take-off

To understand we need to go back to pre-industrial society. At the time, a small population, most of whom were disfranchised peasants, worked in agriculture. People’s lives were confined to the village they were born into. Living standards were low and revolved around subsistence and a daily struggle to get enough food to eat. Limited industry meant there were fewer consumable goods.

Of the available goods and services, not many people had any disposable income to buy them. This all meant the material and energy inputs needed to provide for human needs were small relative to the large, but non-growing global ecosystem.

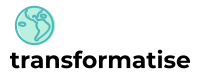

Pre-industrial society therefore existed in what’s known as ‘an empty world’. The image of an ‘empty world’ below shows the economy as a nested system within the natural world:

Earth is a closed system to matter, so no inputs enter the Earth and no outputs exit. Hence, why it’s referred to as ‘the finite global ecosystem’ because the material world around us is limited to what is on Earth. Earth however is an open system to energy, which it receives in abundance from the Sun as solar energy. Solar energy enters Earth and exits as heat.

The arrows moving into the economy in the image above represent sources of energy and resources used to make all the goods needed to sustain the population. The arrows moving out of the economy represent wastes exiting through sinks after they’ve been used. Some of the energy and resources from economic activity get recycled as inputs, but most is processed linearly.

The Industrial Revolution triggered a transformation in our relationship with the material world. In The Age of Revolution, the historian Eric Hobsbawm explains that for the first time in human history, “the shackles were taken off the productive power of human societies, which henceforth became capable of the constant, rapid…multiplication of men, goods and services”.

Economists refer to this moment as the ‘take-off into self-sustained growth’. This process went into overdrive after the end of the Second World War.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the global economy grew sixfold. Between 1950 and 2010, the human population nearly tripled. In 1950 the world produced 1 million tonnes of plastics; today we produce around 300 million tonnes. In that time, energy consumption tripled.

The quantities of nitrogen synthesised (mainly for fertilisers) rose from under 4 million tonnes to more than 120 million tonnes. The number of McDonald’s restaurants, an icon of globalisation, increased from one restaurant in America in 1954, to over 36,000 restaurants in over 100 countries by 2021.

Every conceivable thing has increased exponentially, from air travel to automobiles to telecommunications; the Great Acceleration (as it’s known) in human productivity has created an avalanche of consumable goods and services that have led to higher living standards.

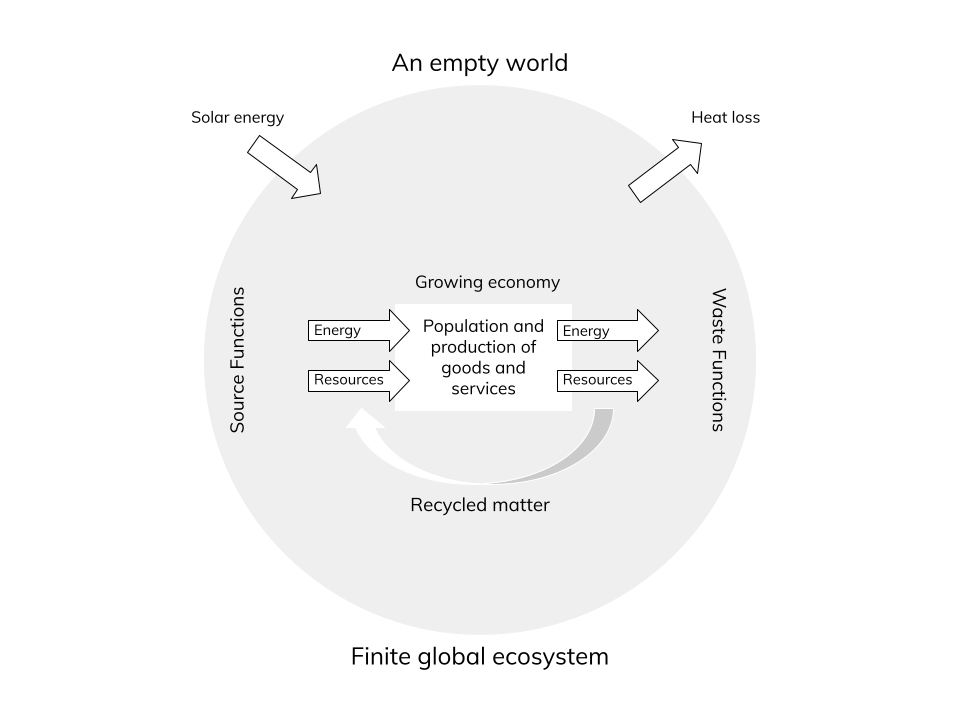

This explosion of human activity, fed by rapid economic growth, means that post-industrial society has now created a ‘full’ world.

In a full world, a larger population needs greater amounts of energy and material inputs to support human needs. Now, the economy is large (and still growing) relative to the non-growing global ecosystem.

Limits to growth

The upside of economic growth is that it led to miraculous increases in living standards. But there was always a downside to be paid. That downside is that growth requires ever-increasing throughputs of energy and resources. In Beyond Growth, Herman Daly explains that while it was reasonable to ignore throughputs in an ‘empty’ world, in a ‘full’ world, it’s “highly unreasonable to continue omitting the concept of throughput” because it’s becoming increasingly apparent that throughputs are limited.

Take oil production. There’s been speculation about when world oil production would peak since the mid-1800s. It now appears that time isn’t far off.

In The inevitable peaking of world oil production, the physicist Robert Hirsch points out that since 2005 oil production has declined in 33 of the world’s 48 largest oil-producing countries. He argues that as peaking approaches, oil prices and “price volatility will increase dramatically, and, without timely mitigation, the economic, social, and political costs will be unprecedented.”

The decade following peaking will see “dramatic increases in inflation, long-term recession, high unemployment, and declining living standards.” The issue with oil is an issue with the economy writ large. The material world is finite; when you combine that fact with the rules governing energy, the inescapable conclusion is that never-ending growth on a finite planet can’t be sustained.

This rather large elephant reared its head with the publication of The Limits to Growth in 1972. The book argued that if population, resource use, and pollution kept increasing on our finite planet, eventually, economies would face environmental limits to growth, precipitating collapse sometime in the twenty-first century.

The most graphic symbol of limits to growth is ecological overshoot. Overshoot is where humanity’s demands on the natural world exceed what it can renew in a year. And we’ve been in such a state since the 1970s.

In its Living Planet Report, the World Wildlife Fund argues overshoot remains possible — for now — because “we can cut trees faster than they mature, harvest more fish than the oceans can replenish, or emit more carbon into the atmosphere than the forests and oceans can absorb.”

The inevitable result is that inputs of energy and resources are becoming scarcer, and wastes (like carbon emissions) are having increasing environmental impacts. As Rachael Beddoe argues in Overcoming Systemic Roadblocks to Sustainability, the climate is changing because an ecosystem service is “being consumed at a rate unsustainable by the surrounding ecosystem — Earth.”

Rather than being a ‘problem’ that must be ‘solved’, the climate crisis is a symptom of this system. The cause is how we conceive of social development; the cause is consumerism and how we define social success; the cause is a belief in never-ending economic growth.

These aspects of our social construct drive behaviour that leads to overshoot. It seems obvious that solving the problem involves focusing on the causes of the disease rather than the symptoms.

And that’s where we have a massive problem.

The terrifying risks of economic growth

Whatever way you look at it, economic growth can’t be sustained if we want to maintain a healthy ecosystem. But it must be maintained if we want to maintain a healthy social system. This tension is the reason we’re on the cusp of imminent collapse.

As we progress into the twenty-first century it’s going to become harder to maintain growth for two fundamental reasons.

1. Resource scarcity

Limits to growth will eventually come in the form of resource scarcity — we will run out of inputs used to create goods and services. If we hit resource limits, it will lead to a downturn in economic activity

Should GDP (the metric used to measure whether the economy has grown) decrease it will lead to recession.

Recession often means bankruptcies and fewer businesses. Fewer businesses mean more redundancies and fewer jobs. Fewer jobs mean less money in people’s pockets. Recessions tend to be accompanied by inflation and higher interest rates, driving the cost of living up. Should GDP continue to decrease it will ultimately lead to depression, leading to dramatic decreases in living standards.

Depression will see government revenue plummet, making it harder to maintain critical services — as well as finance national debts. As of 2022, the IMF shows the UK’s debt stood at 100% of GDP, in the US, debt was 110%, in Japan, staggeringly, debt as a percentage of GDP stood at 214%.

These debts can only be financed through increasing economic growth. In the event of a long-term downturn in the economy, countries will be unable to meet payments and will go bankrupt, sending the global economy into a devastating death cycle.

2. The ecological crisis

If resource scarcity doesn’t hit first then the climate crisis will put the brakes on growth. The climate crisis will translate into wave after wave of weather extremes that will create scarcity, price shocks and decreasing living standards.

In short, they’ll destabilise the world economy, making it harder to maintain growth — setting in a similar set of events as resource scarcity.

Should we continue to pursue growth and undermine the resilience of the natural world we could trigger tipping points that will transform the environment into a new unknown state. One that may not be conducive to providing the conditions we depend on for our survival.

The ultimate risk of a transformation of the natural world is human extinction — a risk that is dangerously unexplored but is an eventuality that has become distinctly possible.

Whatever way you look at it, it’s going to become harder to maintain economic growth. If growth can’t be sustained then our social system is going to collapse.

Locked in

The only road ahead is to recognise growth as a development path is unsustainable. What’s required is a shift to a post-growth economy, that seeks to provide for human needs within environmental limits. Those are, after all, the planetary limits we live within, whether we like it or not.

The challenge in doing so is that economic growth has become the secular religion of modern society.

We all come to learn how to conform to this religion through our socialisation. The process of socialisation means we come to see the world the way it is as an unquestioned truth, the only way it could possibly be. This forms the foundations of the social construct and translates into the norms, values and conventions that drive our behaviour.

That the majority conform to an all-consuming belief system creates the resilience societies are built on. But that strength becomes a debilitating weakness if (like us) society is changing the environmental conditions it depends on. It also compels maladaptive behaviour that may work to prevent the required adaptations and reinforce the problem trying to be solved.

As the anthropologist Norman Yoffee puts it, “cultures become too specifically adapted to contend with the invariably independent variable of environmental change and succumb. Thus, cultures develop internally, but they collapse from some external condition.”

In other words, societies collapse because they try to stay the same in the face of changing environmental conditions.

The tantalising opportunity of collapse

What, then of the opportunities referred to in the title of this article?

We must move to a post-growth economy, there is no alternative. Doing so will transform society in ways that are difficult to comprehend. A post-growth society will create radically new forms of meaning, and radically different ways of interacting with one another and the natural world.

Moving to a post-growth economy will be chaotic because every element of our reality is fed by or depends on growth. It simply can’t be done without massive upheaval. And that’s why collapse creates a tantalising opportunity.

Once we hit limits to growth, economic collapse will wreak havoc on the global economy. Chronic shortages and rampant inflation will see dramatic decreases in living standards. Inevitably, wars will break out as countries fight over critical resources. If wars between countries don’t break out, civil wars will as governments become incapacitated by crisis after crisis.

In short, limits to growth will lead to economic and social meltdown. It’s in that context — where growth demonstrably fails as a belief system — that the need to shift to a post-growth economy will become self-evident. And that’s why breakdown creates a tantalising opportunity. It will create the required conditions where a new vision of society becomes necessary. It will also create the conditions where revolutionary groups can take the reins of power and implement such ideas.

It may well be a political expression that the darkest part of the night comes just before dawn. Well, we are moving into darkness, and while limits to growth will create profound suffering there is also that hope in the distance. The hope of reforging the economy and society so that it works for everyone. Now that’s a dawn worth fighting for.