Backcasting could support the transformation of society onto a sustainable path

Our behaviour is triggering some pretty horrifying environmental changes. Changes that have, for example, induced a climate crisis that risks transforming the natural world into a hostile state. If we don’t sustain the environment, we can’t sustain society. No one wants that to happen, which is why there is such an urgent need for social transformation.

A challenge we face in triggering such a transformation is how we see the problem. When solving problems we tend to adopt a ‘forecast’ approach. That is, we make predictions about what the future will look like. We then look to make changes that will help to achieve or avoid that future scenario.

Climate models help us predict the future climate. Those models reveal the urgent need to reduce emissions, hence why ‘Net zero’ has become a globally recognised goal to avoid the worst impacts of the climate crisis.

Net zero means reducing emissions to the point where residual emissions can be safely absorbed and durably stored by nature. The question we must be asking about this goal is, if we achieve net zero by 2050, will it create a sustainable society?

It might, it might not.

No one has bothered to ask the question because no one knows what a sustainable society looks like.

That’s why backcasting, if utilised, would be such a powerful tool when it comes to helping us move to a sustainable society. Backcasting is all about envisioning a future state that is unencumbered by the present.

Once the future is envisioned, you can then look to assess the current reality and design a strategy that moves you from where you are to where you need to be.

The first step in backcasting is to create a vision of success. So what exactly does a sustainable society look like?

Where we need to be

When we say sustainability, we are referring to a destination where society creates prosperity for all in ways that don’t harm the environment.

To achieve such a state we need to think about what a safe and just space for humanity looks like.

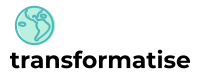

The Doughnut is a term coined by the economist Kate Raworth to define such a space.

The inner ring of the Doughnut, as shown in the image, comprises twelve foundations each person needs to live a fruitful, fulfilling, prosperous life. Below the social foundations lie shortfalls in human well-being. Should a shortfall exist it means sections of society are lacking one of the essential ingredients needed to live a fulfilling life.

Creating a just space for humanity involves meeting the social foundations for each person.

The outer ring of the Doughnut comprises nine planetary boundaries. These nine boundaries — or biological processes — are critical to maintaining the stability and resilience of the Earth system.

The safe operating space defines a space we must operate within to maintain the conditions we depend on for our survival.

Should we overshoot the ecological ceiling it means we are placing pressure on one of these critical processes that risks triggering irrevocable and catastrophic changes.

Creating a safe space for humanity involves making sure the ecological ceiling isn’t breached.

Combining the inner social foundations, and the outer ecological ceiling translates into a vision of sustainability. That vision can act as a compass, a destination if you will, that can guide decision-making.

We have a destination. The next step in backcasting is to determine the current reality to assess how far away we are from creating that safe and just space for humanity.

Where we are environmentally

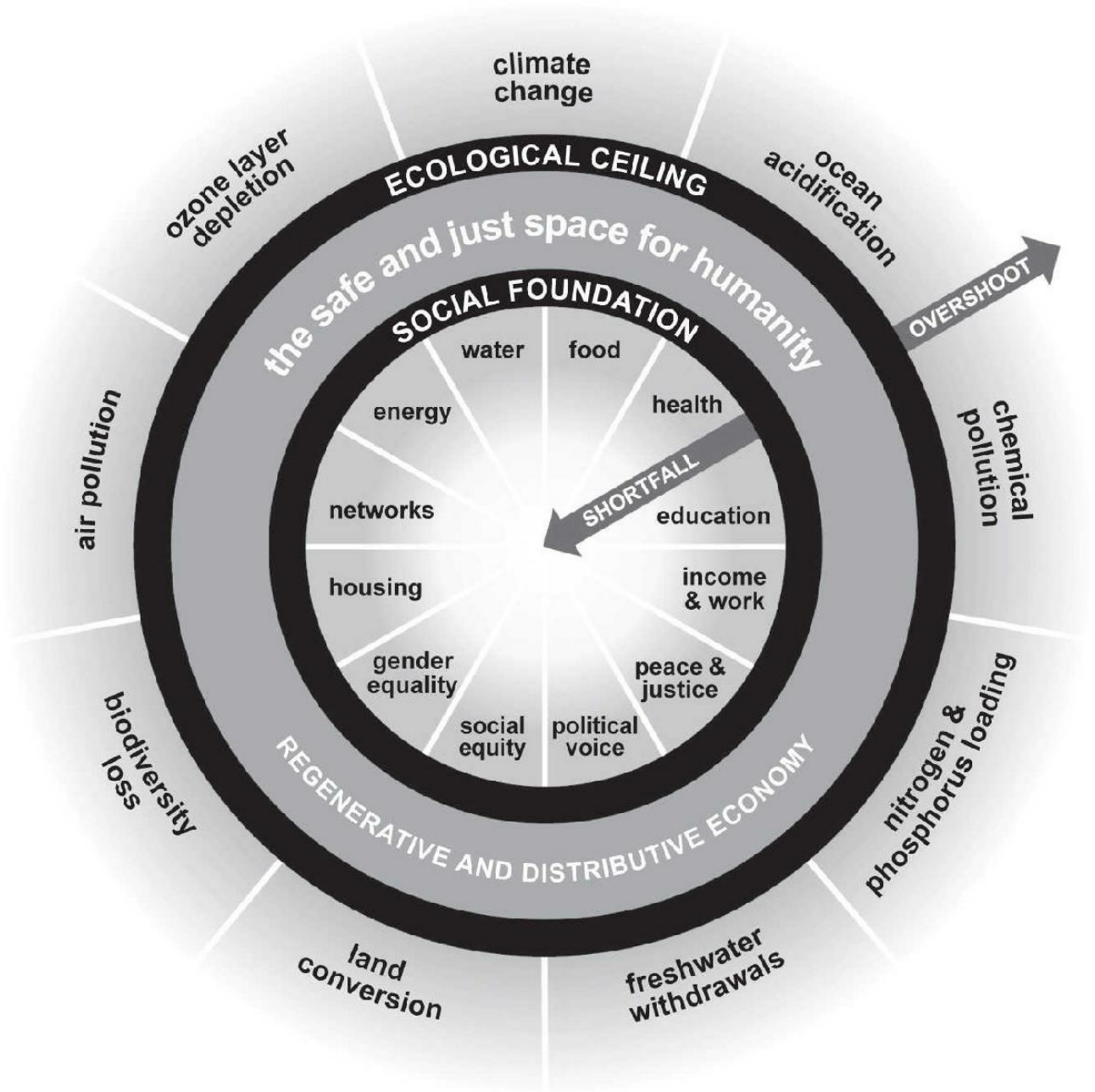

When it comes to creating a safe environment, the image of the nine planetary boundaries shows the ‘safe operating space’ in the middle — this is where each biophysical process must remain to maintain a stable environment.

The ‘boundary’ marks a point between the safe operating space and a zone of increasing risk. Our behaviour is unsustainable because we produce (and consume) goods and services in ways that are pushing these processes into the zone of increasing risk.

And the longer this unsustainable behaviour continues, the further the process moves away from the safe operating space. That’s why it’s called the zone of increasing risk. The further a process is driven away from the boundary, the greater the risk of triggering tipping points.

Tipping points occur when a critical threshold is breached. As soon as it is, it leads to change. We don’t know how much pressure a process can be placed under before it hits that critical point of no return. We also don’t know how triggering a tipping point could impact the integrity of the Earth system. So changes are impossible to predict, but when changes happen, they tend to be abrupt and irrevocable.

What we do know is that sustaining a global economy of this size requires massive inputs of energy and resources. As a result, our influence on the nine critical processes has become enormous. This has led to six processes — climate change, land-system change, biosphere integrity, biogeochemical flows, novel entities and freshwater change — breaching boundaries and entering the zone of increasing risk.

While useful in visualising how our actions are translating into an environmental catastrophe, the framework also determines what needs to be done to either move a process back into the safe operating space or to make sure it stays there.

For example, looking at the CO2 concentrations part of the climate change boundary, to move CO2 concentrations back within the safe operating space, atmospheric concentrations of CO2 must reduce from their current levels of 422 parts per million (ppm) to below 350 ppm.

Where we are socially

When it comes to social sustainability, things aren’t looking much better. As Raworth points out in Doughnut Economics;

“Worldwide, one person in nine does not have enough to eat. One in four lives on less than $3 a day and one in eight young people cannot find work. One person in three still has no access to a toilet…one child in six aged 12–15 is not in school, the vast majority of them girls. Almost 40 percent of people live in countries in which income is distributed highly unequally. And more than half of the world’s population live in countries in which people severely lack political voice.”

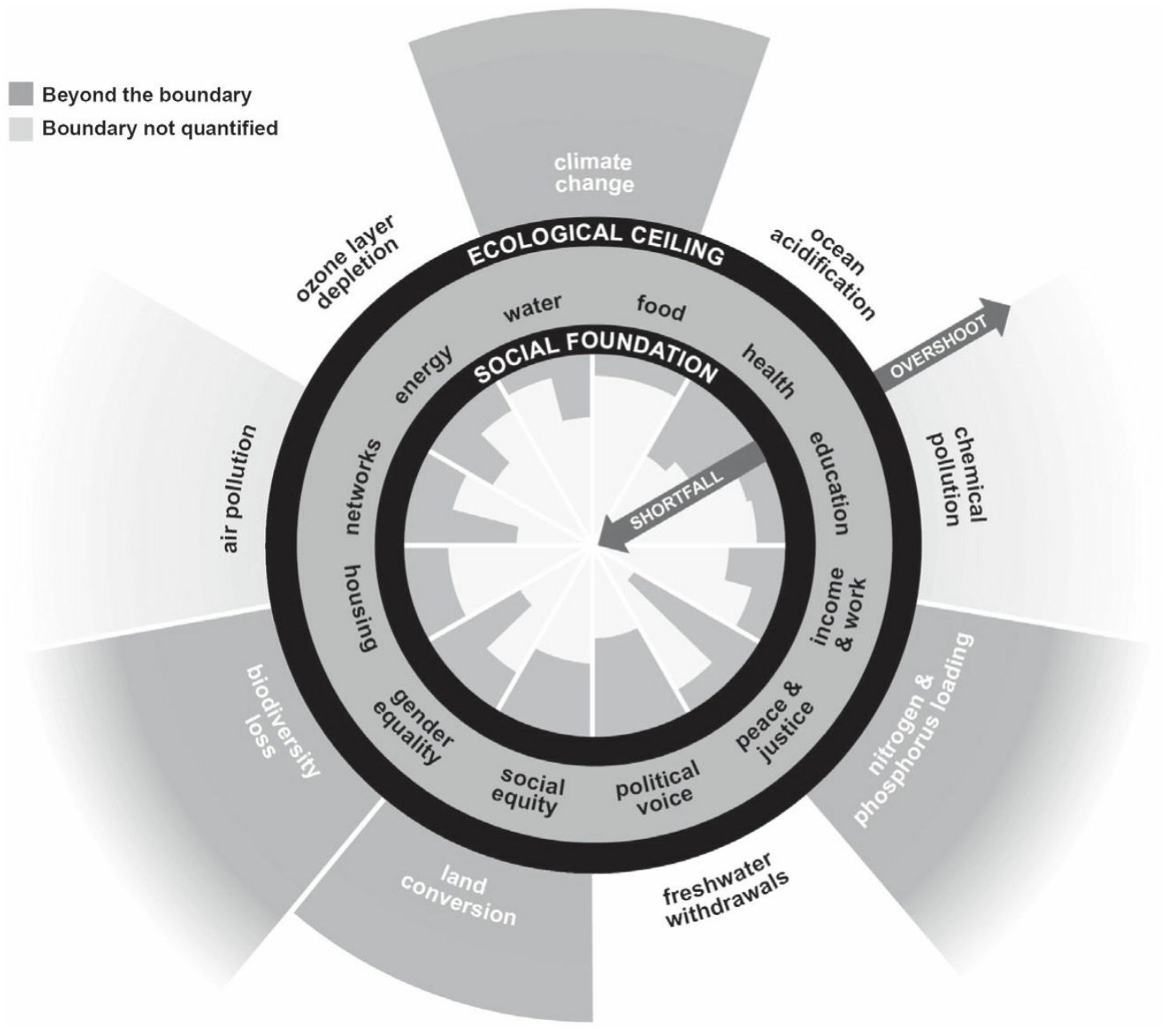

What this all means is that all twelve social foundations are experiencing a shortfall. In the image, each foundation has a wedge protruding from it. The further away the wedge extends from the foundation, the more people are experiencing a shortfall.

Creating a safe and just space for humanity involves decreasing each shortfall so that every person has their social foundations met. Simultaneously, the six planetary boundaries must be moved back into the safe operating space while ensuring the other boundaries remain there.

That challenge would be monumental in itself, but add into the mix the fact that the global population is expected to increase to nearly ten billion people by 2050 and over 11 billion by 2100 and this is, by a long shot, the greatest challenge humanity has ever faced.

A profound dilemma

The fundamental problem at present is that social development (as we currently conceive of it) means reducing the social foundations will increase overshoot. Expected growth rates of the global middle class highlight the conflict of interest.

It should be a cause for celebration that the global middle class — defined as those spending between $10 and $100 a day — is set to increase from two billion people today to over five billion people by 2030. More income will mean each person has a greater ability to meet their needs, helping to reduce some of the social shortfalls. But with increasing incomes comes a greater ability to consume more.

The growing middle class will want to travel, they’ll want to buy electronics, they may want to eat meat — and they have every right to do so. The problem is that with a greater ability to consume comes the increasing energy intensity of lifestyles.

In Prosperity without Growth, Tim Jackson gives a sense of just how problematic the current development path is. He imagines a scenario where creating a just world is taken seriously, and global incomes converge by 2050.

For that to happen, if rich countries grow at two percent each year, middle-income countries would need to grow around 7.6 percent each year, and low-income countries by almost 12 percent. In this hypothetical world, that would mean that by 2050 the global economy will be 11 times bigger than in 2016. Beyond 2050, if incomes continue increasing by two percent each year, the economy will be 30 times larger by the end of the century.

We are already in a state of overshoot — hence why six of the planetary boundaries are in the zone of uncertainty. In fact, we require 1.7 Earths to provide for the needs of society now, so what would overshoot look like if the economy is 30 times larger?

An economy 30 times larger than today is self-evidently impossible because resource and energy inputs will have to increase enormously, exacerbating overshoot.

Ecological processes will be driven further away from the safe operating space, increasing the risk of triggering tipping points that will transform the natural world into an unforgiving new state.

This will create profound stresses on our ability to continue to provide the social foundations for those who currently have them met, let alone reduce shortfalls for those who don’t.

If this future hypothetical world sounds far-fetched, consider that global economic output is expected to grow by three per cent per year until 2050.

Sustainable Development

We now have a vision of sustainability. We also have an awareness of our current reality. The next step is to create a strategy that will take us from where we are, to where we need to be.

The question that is central to achieving that goal is how can we reduce the social foundations while also reducing overshoot so that each biophysical process moves back into the safe operating space?

That question is where we hit a giant obstacle on the road to destination sustainability.

Social development creates a profound dilemma because what’s clear from the connection between living standards and environmental impacts is that how we conceive of development reinforces overshoot. That’s why the climate crisis is proving so controversial.

It’s not so much that the climate is changing, which is obvious for all to see. But what drives climate change is high and rising living standards. The implication is that to reduce overshoot and bring the nine processes below the ecological ceiling living standards must be questioned.

Those enjoying high living standards aren’t going to do that, because they have everything to lose should the connection be made to living standards and environmental impacts.

What makes the current state of affairs so morally questionable is that the more people who achieve high living standards, the worse the environmental situation becomes.

What becomes apparent looking at the inherent tensions in society is that to move to where we need to be requires revolutionary change.

What’s needed is a redesign of society. A redesign of the economy. A redesign of how we come to view social success. What’s needed is nothing short of the greatest social and economic transformation the world has ever seen.

There are plenty of people who will resist such a transformation because they are the winners in the status quo. But the reality of overshoot means our fate is sealed. Catastrophic environmental changes are on the horizon. Those changes will translate into wave after wave of social crisis. Which could be exactly what’s needed to create conditions where the required transformation becomes possible.

What should bring hope in a time of despair is that we have the technological ability to achieve such a sustainable future. We also have an army of environmentalists who are highly motivated to support such a transformation. A sustainable future is on the horizon, but it would be naive to imagine the journey to get there will be plain sailing. We are in for a brutally rocky ride, but should we reach destination sustainability, let us hope the ride was worth it.