Any effort to ‘Making America Great Again’ must involve wealth redistribution, the exact opposite of what rich Americans want

Between 2016 and 2019 the total share of income going to the richest Americans increased by 17 percent. That statistic shows Donald Trump’s first attempt to ‘Make America Great Again’ focused on tax breaks for the rich. If making America great again involves a dramatic increase in inequality, then Trump’s presidency was a resounding success. There’s just a slight issue with this vision of a ‘great America’; increasing inequality is tearing the country apart.

The Trump administration is by no means the first that has sought reforms to cut taxes for the richest. Such policies have been in vogue since Ronald Reagan came to power in 1980 lionising the powers of free markets through a certain ideology — neoliberalism.

At the heart of neoliberalism lies an assumption — markets are good and will produce efficient and fair social outcomes. That’s if they are left alone by the Government, which is bad and produces inefficient and unfair social outcomes.

To put it another way, neoliberalism unleashes the individual from the ‘shackles’ of government regulation. Work hard, show resilience, be persistent, and the market will reward you fairly.

This assumption is important as it creates the justification for reducing taxes on the rich. The idea centres on the trickle-down effect.

When you reduce taxes on the richest and largest companies it has two effects. On one hand, it reduces government revenue, meaning the government has less money to spend, and thus fewer opportunities to meddle in society.

On the other hand, it increases the wealth of individuals. Now, that wealth isn’t used for them to live in decadent splendour. No, no, no. The idea is that they’ll channel tax savings back into the market through wise investments. Such investments from the people who know the business of business will help to stimulate the economy and ultimately lead to economic growth.

A growing economy leads to increasing incomes — hence the idea of a ‘trickle-down effect’. Tax cuts for the rich are good for everyone then, because if people have more money in their pockets, they’ll be happier as they can consume more — that is another assumption conventional economics makes, anyway.

A flawed assumption

The problem with this belief — and it is a rather inconvenient one — is that taxing the rich less benefits the rich, while leaving everyone else worse off. This is because it allows the richest to take a disproportionate amount of wealth generated through economic growth.

After the 2008 financial crisis, the richest 1% in America captured 95% of post-financial crisis growth. This didn’t happen by chance. Nor did the bottom 90% become poorer through bad luck.

Runaway increases in executive pay reinforce the problem of widening gaps in income inequality. In 1965, the average CEO of the largest US corporations made around 24 times a typical worker’s earnings. By 2007, CEO’s were being paid, on average, three hundred times the earnings of an average worker. In 2021, Apple’s CEO, Tim Cook, earned nearly $100 million, over 1,465 times the median pay for Apple employees of $68,254.

Economists argue workers are paid in proportion to the value of their productive contributions. If CEOs are being paid so much more, it must be because their productivity has increased.

While it feels reasonable that a CEO earns more than an average employee, it would take a leap of the imagination to imagine a CEO has become 1,400 times more productive than an employee.

It’s in the interests of CEOs to reward themselves highly while keeping employee wages low. Lower employee wages increase margins, helping to increase profits. Higher profits increase share prices, resulting in larger bonuses for them and higher value for stock options.

And with the demise of trade unions, employee rights have dwindled while the power of corporations over workers has increased. Now, by and large, corporations dictate the terms that employees have little option but to accept.

As a result, productivity increases and growth in output have not translated into a proportional rise in workers’ earnings. In Winner-Take-All-Politics, Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson argue that in the US, “between 1973 and 2014 net productivity grew by 72.2 percent, yet inflation adjusted hourly pay for the median worker rose by just 8.7 percent.”

America is producing more than ever before, but the increased prosperity is being filtered into the hands of a tiny minority.

In The Conscience of a Liberal, the economist Paul Krugman explains how apologists for rising inequality argue it “is mainly caused by a rising demand for skilled labour, which in turn is driven largely by technological change.”

Based on this argument, rising inequality is the effect of technological change driven by the invisible hand of the market. If this were true, massive increases in income wouldn’t have gone to a select group of highly well-paid individuals, but to a broad group of well-paid workers.

Krugman argues rather than market forces, rising inequality is a product of changing norms and a concerted effort by governments to rig markets in favour of a small elite.

Markets don’t operate based on a set of natural laws, they are social constructions and conform to rules set by institutions and are regulated by governments. When inequality increases, it is a sign that the rules of the game are set up to favour the rich.

The cherry on top is the rich often take advantage of tax loopholes. In 2018, the average income of the top 20 hedge fund managers in the US was $515 million. Yes. Five hundred and fifteen million dollars. The richest, James Simons, took home $1.6 billion.

These wealthy individuals take advantage of the “carried interest” provision in the tax code that allows them to treat their income as capital gains — resulting in a tax rate of just 15 per cent for some of the most well-paid people in the world.

You would imagine the $600 million in campaign contributions the private equity market has made in the past decade, as well as the 200 lobbyists they have on their payroll, helps to derail efforts to close loopholes and increase their tax burden.

The benevolent billionaire

Billionaires are the most extreme example of income inequality. But rather than being viewed as a symbol of inequality, the media worshipped them as if they were deities. Understandable, seeing as becoming a billionaire is the goal of the American Dream.

Seeing as being a billionaire is considered the symbol of social success it’s little wonder that six in ten Americans strive to be mega-wealthy. With nearly 44% believing they can achieve billionaire status.

The likelihood of becoming a billionaire is remote, to say the least. Consider that there are 22 millionaires in America (6.6% of the population). Meanwhile, Forbes’s latest list of billionaires totals 735, which is 0.0002% of the American population of 333.3 million people.

Those individuals now control more wealth — 57 per cent more— than the 65 million households comprising the poorer half of the population.

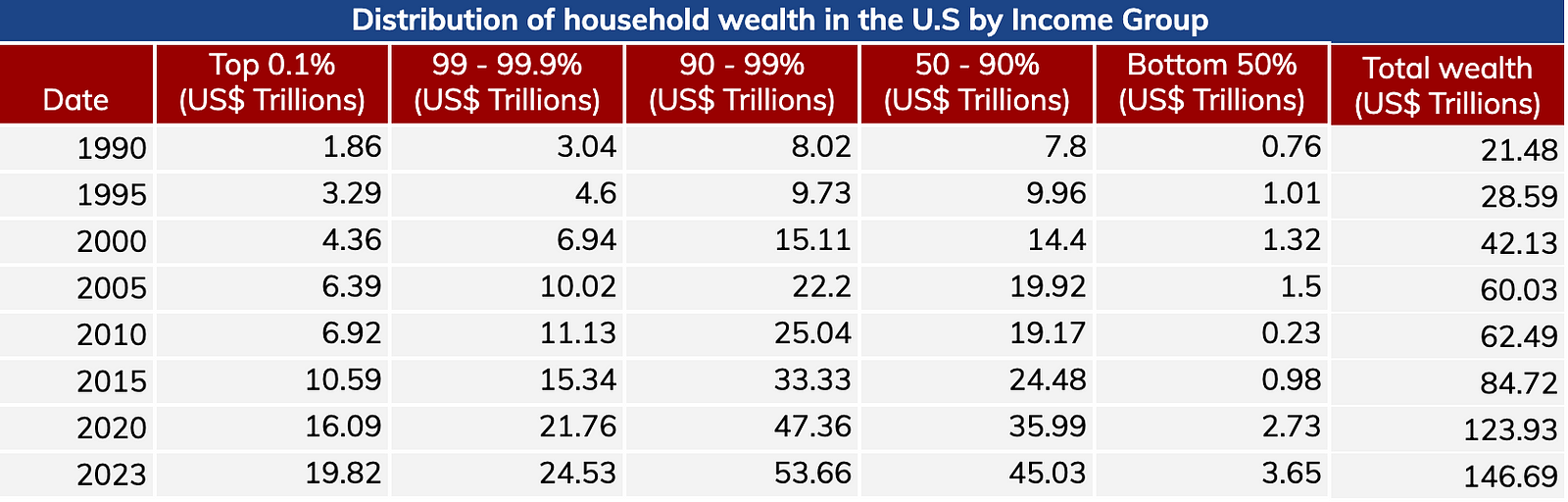

The federal reserves data on income distribution shows that wealth distribution in America has become increasingly concentrated since 1990.

In 2023, the share of wealth held by the richest 0.1% totalled $19.82 trillion. This richest of rich clubs comprises 130,000 households, that have at least $38 million in wealth. The top 0.1% earn on average $3.3 million in income each year. Since 1990, their total share of wealth has grown from 9% to 14% in 2023 — the biggest jump across all wealth brackets.

Contrast this with the bottom 50%. Total wealth in the bottom half of the population totals $3.65 trillion, or 2.4% of total wealth. When you consider that wealth is shared by 166.6 million people, it works out to $22,682 of wealth per individual.

Corrosive impacts

In The Spirit Level, Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson show that less equal societies lack social cohesion as there is less trust between people. They also have higher crime rates, ill health, obesity and a host of social problems when compared to more equal societies.

You would expect wealthier societies to have higher life expectancies. But, in 2019 Costa Rica, with an annual gross national product (GNP) of $12,669, had a life expectancy of 80; in the USA, meanwhile, with a GNP of $65,279, life expectancy was 78.

What determines success in a society is not how rich that society is but how wealth is distributed.

Pickett and Wilkinson argue studies in the USA often report a “28-year difference in life expectancy at age 16 between blacks and whites living in some of the poorest and some of the richest areas.” That’s the difference between living to 60 and 88.

The point is that as inequality increases the bonds that tie society together start to rip apart.

It’s estimated that 78 per cent of Americans live paycheck to paycheck. So three in four Americans struggle to save or invest after paying their monthly expenses. Many depend on credit cards to make ends meet, with the Federal Reserve of New York estimating credit card debt now stands at $1.13 trillion.

Plenty of others are being forced onto the streets. The US census estimates that on a single night in 2023, over 650,000 people in the U.S. experienced homelessness, up 12 per cent from 2022.

After a 44-year campaign to distribute wealth upwards, widening inequalities are creating all kinds of stress points. Inevitably, when things start to go bad in society, views tend to become more polarised about who is to blame, and what can be done about a host of social problems that continue getting worse.

Combined with nationalist fervour, a deep distrust of government, and extreme differences over cultural issues, including LGBTQ+ rights, reproductive rights, and religious freedoms; America is a country divided. The melting pot of discontent has created an “us vs. them” mentality, where people point the finger of blame at one another.

Redistribution, redistribution, redistribution

America’s problems can be attributed, in one way or another, to increasing levels of income inequality.

The rich elite has created an economy where the fruits of everyone else’s labour filter up. The problem is their greed has blinded them to the repercussions of the trickle-up effect.

Decreasing income inequality is fundamental to bringing America back together again. In creating a unified dream where people start working for one another, not working as isolated islands where everyone is competing or somehow out to get you.

There are plenty of reforms that would reduce inequality. The government could close tax loopholes for the rich. It could implement a maximum wealth tax, where any wealth over a certain threshold of say, $100 million, is taxed at 100%. It could implement a maximum wage that is proportionate to a minimum wage, for example, the best-paid person in a company can only earn twenty times as much as the lowest-paid person.

The government could implement so many regulations that help to control the market and ensure the fruits of economic growth are distributed evenly through society.

The fundamental challenge to doing so is that it would undermine the belief in the power of free markets. A belief that has become gospel.

The thing is, people can only be pushed so far. After a 44-year campaign, America finds itself at breaking point. The fear is that victims of this campaign, (essentially anyone outside of the top 10%), are pointing the finger of blame at one another, not at that rich elite that continues to get away with robbing its citizens of their wealth.

Eventually, when the system is at breaking point, the idea that the government has a responsibility to redistribute wealth will gain support, it has to because this state of affairs simply can’t continue for much longer.

Only when the government starts to take back control, only when America is purged of corrupt politicians who only seek to serve the interests of the rich elite, only when policies are designed for the many, not the few. It’s then that the toxicity which is at boiling point will begin to subside. It’s then that America will become great again. Until then, it will continue to tear itself apart.