There’s hope that a window of opportunity remains open. The stats tell a different story.

In May, temperatures hit a national record-high of 52.3 degrees Celsius (126.1 Fahrenheit), in New Delhi, India. The brutal heatwave is another indicator that the climate crisis has begun. And the clock is ticking for us to do something about it. That there is a proverbial ‘ticking clock’, if you will, owes itself to the argument that there’s still time for us to reverse the worst impacts of climate change.

2030 is seen as a crucial date in the ‘save ourselves from the climate crisis’ calendar. This is because, should bold, transformative action take place in the next six years, there is a possibility that we can keep the global average temperature below 1.5 degrees Celsius (°C).

The 1.5°C target is a threshold set by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that must not be exceeded to avoid the catastrophic impacts of warming above 1.5°C. To give a sense of just how bad things could get, a recent paper predicts that should global warming hit 2°C, a billion people will die in the next century.

We are sleepwalking into a world of unfathomable levels of suffering. And yet, the fact the global average temperature has increased by 1.07°C above pre-industrial levels means there appears to be a window of opportunity to trigger a transformation so that we avoid such a future.

The budget

A ‘carbon budget’ gives a sense of what needs to be done by when.

The IPCC has calculated that to have a 50 per cent chance of restricting global warming to less than 1.5°C, the total cumulative CO2 emissions released into the atmosphere since 1850 must be kept below 2,900 billion tonnes.

Between 1850 and 2019, emissions totalled 2,400 billion tonnes — 42 per cent of that total occurred between 1990 and 2019. This means that from 2020, the maximum available ‘carbon budget’ remaining is 500 billion tonnes. The remaining budget increases to 1,150 billion tonnes for a 67 per cent chance of restricting warming to 2°C.

Given the potential deaths associated with a 2°C warmer world, it is alarming that such a budget has even been calculated, but there we are.

To achieve the goal governments, companies, and universities have committed to achieving net zero. Should net zero be achieved we will have arrived at a destination where emissions are low enough that they can be safely absorbed by the natural world (forests and the ocean absorb carbon dioxide naturally).

Achieve net zero by 2050, and we’ll remain below the 1.5°C target.

A bleak assessment

The carbon budget translates into dates that act as key milestones in a journey towards net zero by 2050.

To remain on track for the 1.5°C target, emissions need to peak by, at the latest, 2025, be cut by 43 per cent by 2030 and 84 per cent by 2050. To achieve the 2°C target, emissions need to decrease by 27 percent by 2030 and 63 percent by 2050.

2030 then, represents a key milestone in the journey towards net zero. But rather than galvanising humanity in efforts to rapidly decarbonise the global economy, it’s likely to represent the death knell of any hope of staying below the 1.5°C target.

The reason why is that we’re failing miserably to cut emissions.

In the Emissions Gap Report 2022, the UNFCCC shows that current pledges made by governments to cut emissions will translate into 1,044 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions between 2021–2050, and this figure excludes emissions from other sources.

If forests are close to tipping points (which many scientists believe to be the case), the Amazon could release 90 billion tonnes of CO2, and boreal forests a further 110 billion tonnes. This would wipe out any hopes of restricting global warming to 2°C.

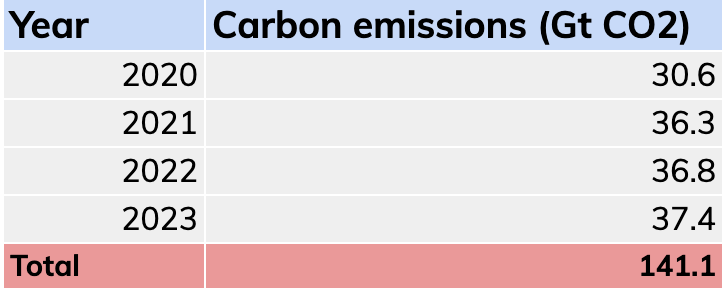

And the situation is only getting worse. As the table below shows, emissions have continued to rise, increasing to a record 37.4 billion tonnes in 2023 (in 2020, carbon emissions decreased not due to decarbonisation efforts but the COVID-19 pandemic).

In the last four years, we’ve blown through 28 per cent of the 500 billion tonne carbon budget. Should current emissions levels be maintained, we’ll exceed the 500 billion tonne carbon budget in 10 years.

That’s why the UNFCCC argues that there is no credible pathway to achieving the 1.5°C target and climate disaster can only be avoided by an urgent system-wide transformation.

The desired transformation

The need for a global transformation raises a different problem altogether. What kind of transformation is needed to save ourselves from climate disaster?

We still need to maintain goods and services that provide for human needs — we can’t maintain functioning societies without them. But what’s required is a rapid decarbonisation of the economy. This involves decoupling any emissions, as well as other environmental costs, from the production of goods and services.

Simultaneously, we must enhance the ability of carbon sinks (those natural ecosystems like forests and oceans) to absorb greenhouse gases. The desired outcome is to reach a point where goods and services are produced in ways where more greenhouse gases are removed through sinks than released through emissions.

This will gradually decrease the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere from their current level of 424 parts per million (ppm), to where they need to be to maintain a stable climate, which is under 350 ppm.

Countless governments, companies, NGOs, Think Tanks, charities and individuals are making efforts to reduce emissions. So why do they keep on increasing?

The reality

Emissions keep on increasing due to the core belief of modern society — economic growth.

The problem with growth as an economic goal is that to achieve it, you must increase output. This involves producing (and consuming) more than you did last year. Making more stuff requires two essential inputs into the economy — energy and resources.

To produce more goods and services, you need more energy and resource inputs. There’s no getting around that fact. Currently, 80 per cent of our energy needs come from fossil fuels. So the bigger the economy gets, the more energy it needs, and the more emissions we produce.

Arguably the crisis we face now began in the 1970’s. That’s when we hit ecological overshoot. A situation where our demands on the natural world have exceeded what the Earth can renew in a year.

It was at that point that concentrations of carbon in the atmosphere went out of control.

In 1950, the concentration of carbon dioxide above Mauna Loa, Hawaii, home to the oldest continuous CO2 measurement station in the world, was 310 ppm. So in over 200 years, the concentration of CO2 increased by 33 ppm (from a starting point of 270 ppm in 1750).

In 1970 concentrations of carbon dioxide had increased to 325 ppm. As of June 2024, they’re at a record high of 426 ppm. So in the last 54 years concentrations of CO2 increased by 101 ppm.

The rapid increase is due to ecological overshoot. We have essentially overwhelmed the capacity of the Earth’s system to deal with the enormous influx of emissions that are associated with economic growth.

The fact economic growth is essential to maintain healthy societies highlights how detached economic thinking and social priorities are from the environmental reality we exist within.

Economic growth as the goal of modern society can’t continue. We either recognise that fact, and start reducing production, or the environment will do it for us.

A paradigm shift

So what’s required to move concentrations of CO2 back below 350ppm?

To reduce emissions, we must focus on the cause of the problem. That cause centres on a growing economy that demands never-ending increases in production.

That’s why the required transformation is a transformation away from economic growth as the foundation of the economy, towards a degrowth economy — an economy where the throughput of energy and resources used to make goods and services decreases, while simultaneously increasing human well-being.

It’s a transformation away from a system that celebrates inequality and towards one where the economy is regulated in such a way that it guarantees each person can live a life of decency and prosperity.

It’s a transformation away from individualism and decadent consumerism towards one where humans find radically new forms of meaning and well-being.

The problem is that society is a construct that is highly resilient to transformative change. Whenever transformative change has happened in the past, it has been through revolution.

What this means is that while there is a desperate need for transformation, that need won’t, in itself, lead to transformation.

We’re locked into a system that can’t question the very thing that leads to increasing emissions. But climate change will eventually pull the brakes on growth because as the effects of climate change become more violent it will make it harder to maintain production.

Decreasing production will lead to scarcity, protectionism and price shocks. The mechanisms needed for a globalised world economy to maintain itself will break down. Rapid increases in prices will see dramatic decreases in living standards.

As scarcity forces us into an auspicious new normal, countries will go to war over scarce resources. Internally, there will be an increase in radicalisation as it becomes clear that a return to the prosperity enjoyed during a time of rampant consumerism is never going to happen.

Instability, unrest, chaos. That will be the order of the day. While hardly desirable, it’s in those types of conditions where revolution becomes a distinct possibility. Maybe amid chaos, we’ll be able to forge the system-wide transformation that’s so desperately needed. Either way, the climate crisis is not a future we can save ourselves from. It’s a future that began some time ago.

Good perspective. Things are, indeed, more or less, like that.