Earth’s chaotic equilibrium means everything will appear ok, until it’s not.

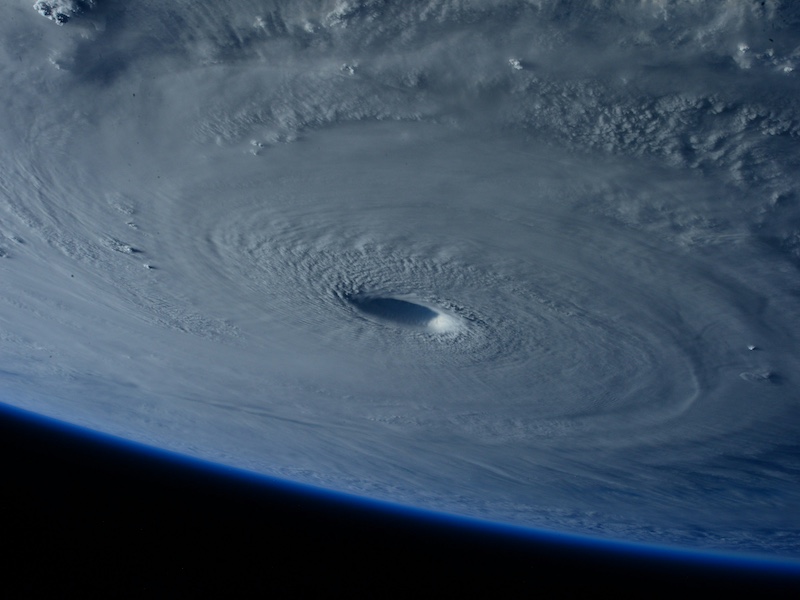

A spring day in England can be an unpredictable affair. Glorious morning sunshine one minute can be replaced by a torrential downpour the next. Five minutes after that, sunshine, ten minutes later, you’re being bombarded by a hail storm. It all feels a little chaotic. That’s because chaos is a key characteristic of the natural world that creates all kinds of problems when it comes to dealing with the climate crisis.

Earth is a complex non-linear system. Complex non-linear systems are defined by having no cause-and-effect relationships between different parts. This means a change in one part can impact lots of different parts in ways that can’t be foreseen.

Put simply, complex non-linear systems are unpredictable and chaotic.

A well-known metaphor for complex, non-linear systems is the butterfly effect, made famous by the idea that a flap of butterfly wings in China can lead to rain instead of sunshine in New York.

But if the flap of one butterfly’s wings can influence the weather on the other side of the planet, wouldn’t it be impossible to predict the weather?

Well, when the meteorologist Ed Lorenz developed the metaphor, it wasn’t to argue that it’s impossible to predict the weather in New York without accounting for the flap of every butterfly wing in China.

He argued that slight differences in the initial conditions can produce vastly different outcomes. To accurately predict the weather next week, you need to know more about the weather today. But due to the vast complexity of the Earth system, even if you could account for the flap of every butterfly’s wings all around the globe, there is a limit to how far into the future the weather can be predicted. That limit is around two weeks.

Chaotic equilibrium

Now, when we say chaotic, we are not saying things are changing every other minute. If that were the case, societies couldn’t be maintained, and we would struggle to coexist with a natural world that in in a state of never-ending transformation.

What we are referring to is unpredictability within a resilient system.

The Earth (as we all know from living on it), is a remarkably stable system. By ‘system’, Earth comprises various ‘spheres’; atmosphere, biosphere, hydrosphere, and geosphere. Each sphere is a system made up of countless sub-systems.

In its Global Environment Outlook, the UNEP points out that these spheres combine to create the “environmental processes that regulate the functioning of the Earth, such as the climate system, the ecological services generated by the living biosphere, including food production, and natural resources like fossil fuels and minerals.”

The various interconnected environmental processes are known as Earth system services. The processes in this interconnected system interact in countless different ways. As the World Wildlife Fund explains in its Living Planet Report;

“Ocean currents bring nutrients from the deep to support productive marine ecosystems. Glaciers act as giant water-storage facilities, while glacial action creates fertile soils. Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is dissolved and stored in the oceans, helping to keep the climate stable. Nitrogen and phosphorus cycles provide essential nutrients for plants to grow, chemical reactions in the atmosphere form protective ozone, and large polar ice sheets help regulate global temperature.”

Over the last 10,000 years, these processes have interacted to form a geological period known as the Holocene — where stable and predictable environmental conditions have prevailed.

Scientists suggest that if left undisturbed, the idyllic conditions created by the Holocene would likely continue for another 50,000 years due to the unusually circular orbit that Earth is currently making of the sun.

‘If left undisturbed’ — that’s got to be the mother of all ifs.

Disturbance

When it comes to disturbance, since 1750 (when the Industrial Revolution roared into life), we’ve spewed 1.5 trillion tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Around 25% of all emissions are absorbed by the oceans, which have become 30% more acidic as a result.

In the last one hundred years, we’ve deforested an area the size of the United States. Oh, and let’s not forget the triggering of the sixth mass extinction event (the first time any such event has been triggered by a species).

The problem with disturbing such a resilient system has to do with the chaos interwoven with it. If the Earth system is too complex to predict weather forecasts accurately beyond a two-week limit, then we can’t say with any certainty how these enormous environmental changes will translate in the real world.

Take climate change — we have highly sophisticated climate models that seek to predict the climate in decades to come. While climate models are useful in giving us the foresight to know our actions are destabilising the climate, they are limited in their accuracy.

This could mean climate targets are way off the mark. The IPCC argues that by keeping the global average temperature below 1.5°C we’ll avert the worst risks of extreme weather changes. But the preeminent climate scientist James Hansen disagrees. He has written extensively on this subject arguing in A Slippery Slope that “global warming of more than 1°C…would likely constitute “dangerous anthropogenic interference” with climate.”

The point is that there is no way of knowing how much we can push the Earth’s limits before its resilience begins to break down. That’s highly concerning, but the limited powers of climate models are the tip of the iceberg.

The great unknown

Lying underneath the surface is the terrifying risk posed by tipping points.

Tipping points occur when a critical threshold is breached in the Earth system. As soon as it is, it leads to change. Put another way, a tipping point is a point of no return.

An example is the Arctic, which is warming at four times the global average. Warmer temperatures mean a larger proportion of sea ice melts in the summer. White sea ice reflects up to 80 per cent of the sun’s heat away from Earth, but as it melts, it’s replaced by dark ocean water that absorbs 90 per cent of the heat.

The albedo effect, as it’s known, amplifies warming and creates a positive feedback loop, where warmer temperatures lead to more sea ice melting, which leads to more sea ice being replaced by the ocean, which leads to more melting, and so on. This warming effect means it’s a matter of when, not if, the Arctic becomes ice-free in the summer. In other words, the region has crossed a tipping point.

What’s so concerning about tipping points is that given the Earth comprises various interconnected systems, once one is crossed, it could create a domino effect that will set in motion radical environmental changes.

Seeing as it’s impossible to model and forecast the impacts of tipping points, they aren’t integrated into climate models. This explains why many climate scientists believe climate models are gravely underestimating future environmental conditions.

What is known with a high level of confidence is that the risk of breaching tipping points increases as global temperatures increase. And mounting evidence shows current levels of warming (at just under 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels) have already led to several critical systems breaching tipping points.

Devastating risks

When we talk about debilitating changes to the climate, we aren’t referring to some future state. Between 2000–2020, almost 7,500 extreme weather events were recorded, claiming 1.23 million lives, affecting 4.2 billion people and causing $2.97 trillion in economic losses.

In 2022, 55 states were affected by violent conflict, also the highest level since World War II. The human costs of conflict are high and rising with women and children affected the most. It is estimated that 20–30% of women in conflict settings experience sexual violence. In 2022, conflict and insecurity were the most significant drivers of high levels of acute food insecurity for around 117 million people in 19 countries and territories.

When it comes to how weather extremes will translate into social tensions, food insecurity is right at the top of the list. Shifting weather patterns will likely lead to increased risks of droughts. Droughts will see an increased risk of crop failure, which leads to increased risks of shortages. With a growing population, this will see price spikes and inflation spiralling out of control.

As the impacts of the climate crisis become more aggressive, shortages could mean the benefits of selling products and produce at higher prices in the market are outweighed by the need to maintain law and order at home.

Should countries become more protectionist — which historically tends to happen with food shortages — it would lead to a breakdown of the mechanisms needed for free trade.

In its Climate Change Risk Assessment, Chatham House argue that with chronic shortages, “a societal consensus could emerge that the free market economic model is unsustainable, and governments could move towards constraining people’s consumption…this could lead to macro-economic discontinuities with far-reaching consequences for inflation rates, asset prices, jobs and livelihoods.”

Our lives have always been defined by a basic social expectation of the freedom to choose what we do, say and buy. Governments encourage increasing consumption because it’s so important for a thriving economy, and companies depend on it to maintain profit margins.

The idea that our consumption habits would need to be constrained will feel like a draconian measure, particularly when having more money and possessions than others is considered the epitome of social success. Governments will be aware such extreme measures will be deeply unpopular and are likely to trigger social unrest, but they’ll be faced with no other choice.

Consumerism is likely to end not because of a global epiphany that chasing material success leads to mutual unhappiness, but because the avalanche of consumable goods will run dry. Even if people want to continue ‘living their best lives’, as the venerable saying of our time goes, they won’t be able to.

The risk of food shortages is coupled with the risk of water scarcity, climate refugees, a breakdown of cooperation in the market, economic shocks, and inflation. In On The Threshold, Thomas Homer-Dixon argues that when you combine the risks, the impacts of environmental changes are set to increase “the level of stress within national and international society, thus increasing the likelihood of many different kinds of conflict and impeding the development of cooperative solutions.”

Inevitably, the risk of war, including nuclear war, will increase as countries seek to gain control of critical resources.

Homer-Dixon predicts that environmental changes could “cause the gradual impoverishment of societies…which could aggravate class and ethnic cleavages, undermine liberal regimes, and spawn insurgencies.” This is the ultimate risk of a changing climate.

Blinded by arrogance

There is an arrogant assumption that because we can mould the world to suit our purposes we are in control. If you can’t predict the changes you’re making to a system, then you’re hardly in control, are you?

So how can we ever manage the complexity and chaos inherent in the Earth system? A logical starting point is to acknowledge that we are not in control. Once this is generally understood the need to embrace the precautionary principle becomes clear.

As the International Institute for Sustainable Development argues, the precautionary principle is an “attempt to give the notion of precaution — understood as a form of addressing risk — legal status. Its core elements are the need for environmental protection; the presence of threat or risk of serious damage; and the fact that a lack of scientific certainty should not be used to avoid taking action to prevent that damage.”

In other words, it is safer to assume the worst, and plan accordingly, than to assume that we can continue with business as usual and that a silver bullet (in the form of a technological breakthrough) will somehow save the day. Because the risk of assuming everything will be okay is social collapse. The risk of precaution is that we move towards a sustainable path at a more aggressive rate.

It is a no-brainer, and yet, the reason we are ignoring the enormous risks we face is the same reason climate denial is alive and well. There are powerful vested interests who have everything to lose if we do start to make teh necessary transformation of the economy and society that is required.

There also happens to be a psychological element. Being precautious flies in the face of a culture driven by exceeding boundaries. By going faster, flying higher, growing quicker. For the last few hundred years we have been driven by progress, not by being precuatious.

We are veering towards catastrophe at a rapid rate of knots but the chaotic unpredictability of the Earth works like a bubble wrap that justifies the continued celebration of suicidal behaviour. The problem with living on a chaotic planet is that Earth’s chaotic complexity makes it impossible to say when it has become a matter of time before the bubble wrap pops. And social chaos will be no fun, no fun at all.