The vault stores that which matters most

Deep in the Arctic Circle on an island just off the coast of Norway, lies a vault that just might save humanity from extinction. In the vault, you’ll find no oil, coal, or natural gas. You’ll find no cars, trains, or planes. You’ll find no smartphones, laptops, or TV’s. What you’ll find are seeds. Millions and millions of varieties of seeds.

These seeds are stored in the Global Seed Vault on Spitsbergen, part of Norway’s Svalbard archipelago. The vault highlights that food (and freshwater) is the only thing that matters to survival.

Now, we need far more than food to live prosperous lives. Culture is what gives us our identity, it enriches our experiences, leads to conforming behaviour and creates an unquestioned ‘truth’ about the world and our role in it.

Culture is fundamental to humanity, but the bottom line is that it matters little compared to food. Without food, people die.

It’s been dubbed the “doomsday” vault. The fact such a vault feels necessary tells you everything you need to know about where we are as a civilisation.

We are on the cusp of aggressive and unprecedented climate change that could see global temperatures increase by 4°C by the end of the century. We are in the midst of biodiversity collapse, which is triggering the sixth mass extinction event. We are wreaking havoc on the world’s precious ecosystems. Having deforested 17 per cent of the Amazon Rainforest in the last fifty years, it’s at risk of turning into a savannah.

When combined, we have triggered an ecological crisis that leaves us facing a future of profound unrest, suffering and chaos.

A future where the collapse of our hyper-connected globalised world economy, becomes a distinct possibility. Collapse may well precipitate the extinction of our species altogether — a risk that is dangerously unexplored.

So why on earth does humanity find itself on the brink of global collapse?

We’ve never had it so good

The problem centres on that which matters most, food.

Before the Second World War, chronic malnutrition was the norm, and life revolved around the great economic problem that has blighted humanity — getting enough food to eat.

Since the end of the Second World War, the combination of massive productivity gains organised and distributed through the free market, has triggered a take-off period in the economy that has come to be known as ‘The Great Acceleration’.

The agricultural sector illustrates how transformative the take-off period has been. A recent McKinsey report explains how advances in machinery have revolutionised the “scale, speed, and productivity of farm equipment, leading to more efficient cultivation of more land. Seed, irrigation, and fertilisers also have vastly improved, helping farmers increase yields.”

The Food and Agricultural Organization’s (FAO) data for the years 1961 to 2022 show production of four of the major grains has increased by an average of 267 per cent. Maize output increased from just over 205 million tonnes in 1961 to over 1.1 billion in 2022.

These productivity gains have transformed the world from one of scarcity to abundance.

In a world of scarcity, the economist Robert Fogel points out that families in the UK and France spent between 50 and 75 per cent of their wages on food well into the nineteenth century.

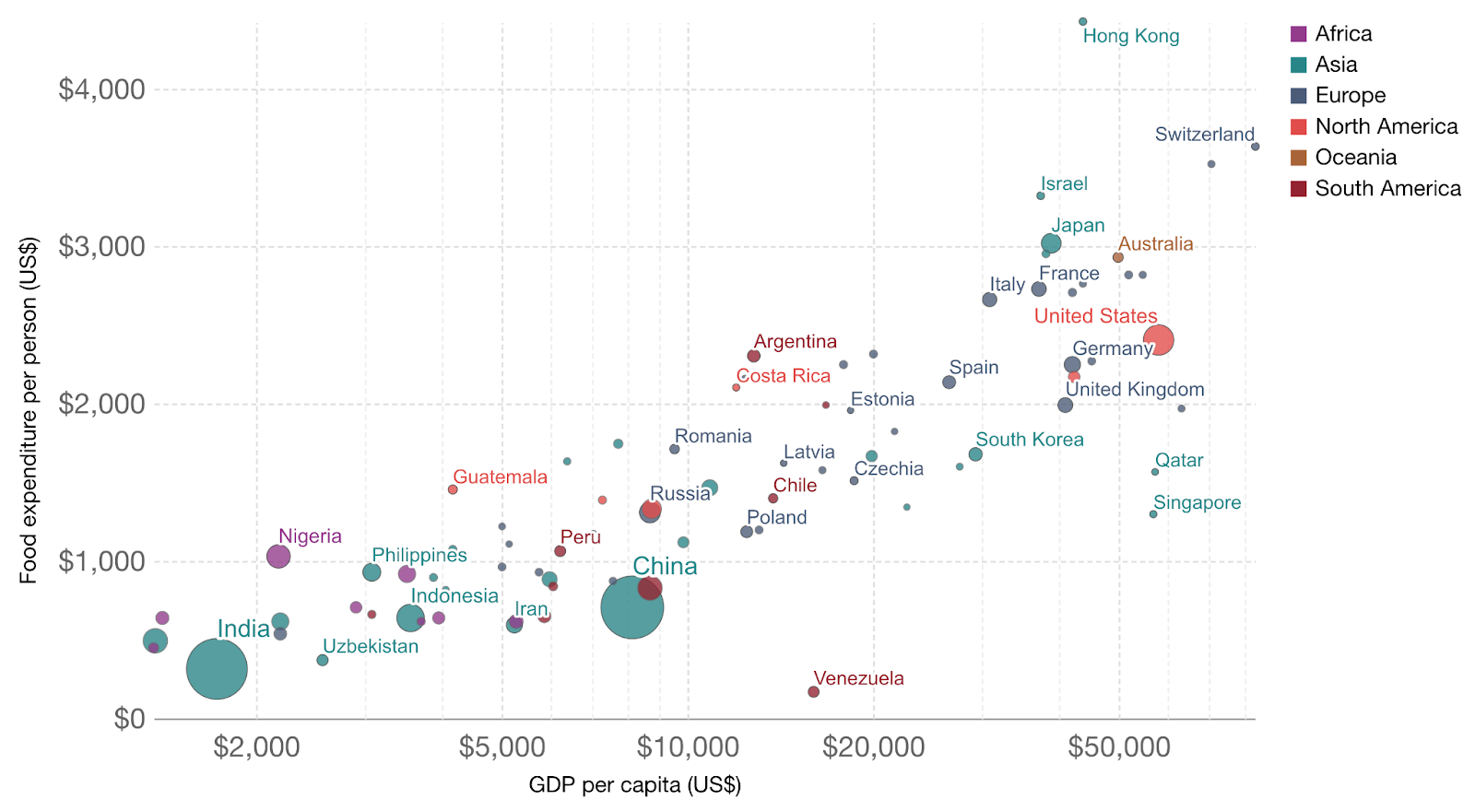

In a world of abundance, food prices have plummeted. The graph shows the average cost of food per person compared to gross domestic product per person (the average wage in a country in a year) for 2016.

In the UK, the cost of food eaten at home made up 4.9 per cent of wages; in Switzerland, the figure was just 2.3 per cent. While food prices remain high relative to wages in some countries (revealing massive differences in living standards), the general trend is that food makes up a far smaller proportion of wages.

As a result, within a few generations, a malnourishment epidemic has been replaced with a global obesity epidemic. There are now more people who are obese than underweight. In the US alone, one in three people is obese.

A culture of consumption

In Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren, John Maynard Keynes argued that once the economic problem is solved, “mankind will be deprived of its traditional purpose.” In a world of abundance, that purpose has been replaced with a culture of consumption.

In a world of scarcity where everyone struggled to meet their basic needs, life was defined by a common struggle to meet those needs. Over 90 per cent of human existence has been within egalitarian societies. Food sharing and reciprocal gift exchange were the foundations of social cohesion.

In a world of abundance, the barometer used to measure success is how rich we are. In The High Price of Materialism, psychologist Tim Kasser argues judgements aren’t based on someone’s “apparent wisdom, kindness, or community contributions, but in terms of whether they possess the right clothes, the right car, and more generally, the right “stuff.””

People’s sense of identity used to be embedded within the community they belonged to. Today, in the anonymity of mass society, self-esteem, feelings of status and self-worth are, as Kasser argues, determined by how your “pile of money and possessions compares with that of others.” The aim then isn’t about having ‘enough’ but having more than everyone else.

In a world of scarcity, the daily struggle to meet the basic needs of food, water and shelter was, as you can imagine, no fun at all. It’s no surprise, then, that those with higher incomes are, on average, happier than those with lower incomes. But beyond the point of meeting the basic needs of food, water and shelter, Kasser points out that increases in wealth, “do little to improve people’s well-being and happiness.”

The economic system is fed from an assumption that increasing incomes make people happier. The fact the evidence suggests otherwise should make us question how we organise the economy. But what makes it truly suicidal are the consequences of development and higher living standards.

Wicked consequences

To produce all of the stuff that feeds consumerism requires inputs of natural resources and energy. Fossil fuels — including coal, oil, and natural gas — supply about 80 per cent of the world’s energy. It’s our increased ability to extract energy from fossil fuels that have created the civilisation we find ourselves in.

When you burn these fuels you extract usable energy, but also the carbon dioxide stored within them.

In How Bad Are Bananas?, Mike Berners Lee calculates how much carbon is released by products we buy or things we do, from a text message (releasing under 10 grams of carbon dioxide (CO2)) to buying 12 eggs (releasing 3.6 kg of CO2), to buying a new car (releasing 6 tonnes of CO2).

The point is that emissions are intertwined with consumption; the more we consume, the more energy-intensive (and unsustainable) our lifestyles are, and the higher our carbon footprint. On an individual level, this means the richest individuals contribute most to increasing emissions. On a national level, this means the richest nations are mainly responsible for historical greenhouse gas emissions.

More people joining the consumer society requires us to produce more goods and services, which results in economic growth. This has led to the global world economy becoming enormous in scale. It’s now so big that we’re in a state of ecological overshoot.

Earth Overshoot Day, as it’s been dubbed, marks the date when humanity’s demand for ecological resources and services in a given year exceeds what Earth can regenerate in that year. In 2023, that ominous date was 2 August. But that date is deceptive. Not every country is complicit in creating overshoot.

The visual shows the date overshoot would land if everyone lived like the people in that country. If we all lived like Indonesians, Earth Overshoot Day would land on November 24 — meaning we’d still be overshooting but would be much closer to living within Earth’s regenerative capacity.

On the other hand, if everyone lived the same way as people in Qatar, we would exceed Earth’s carrying capacity on 11 February — a terrifying prospect.

What’s clear from the visual is that humanity is out of balance. Some countries consume far too much, and others don’t consume enough. What it doesn’t reveal, though, is that consumption is highly unequal and correlates with levels of inequality.

Since 1990, the richest 10 per cent of the world’s population has been responsible for 52 per cent of carbon emissions, while consuming 20 times as much energy as the poorest 10 per cent. Energy consumption varies widely between and within countries. The poorest 20 per cent of the citizens in the UK consume over five times more energy per person than the poorest 84 per cent of people in India.

Another thing is that many developing nations don’t appear in the visual at all. This isn’t because they live in sustainable societies where individual needs are met within environmental limits, but rather the opposite; lots of people’s basic needs aren’t being met.

It should be a cause for celebration then that the global middle class is estimated to reach 5.3 billion people by 2030. But this celebration is tainted by the fact it will lead to increasing consumption and with it increasing dependence on the environment for more throughputs of energy and resources.

From the perspective of social development, more people with more disposable income is a good thing. But from the perspective of the environment, more people joining the consumer class means we exacerbate ecological overshoot.

Social development, as we conceive of it, is incompatible with creating a sustainable society because development is the very thing that leads to unsustainable outcomes.

The high and rising average living standards many now view as a basic expectation would be the envy of previous generations. But, these lifestyles come with disastrous costs — consumer society can’t sustain itself within environmental limits.

In other words, as argued in Underestimating the Challenges of Avoiding a Ghastly Future, humanity is “running an ecological Ponzi scheme in which society robs nature and future generations to pay for boosting incomes in the short term.”

If we continue to pursue economic growth, the economy will continue to grow, overshoot will continue to increase, and the Ponzi scheme will continue getting bigger. It doesn’t seem to add up; something will eventually have to give. That something appears to be the environmental conditions we depend on to maintain thriving societies.

Back to basics

George Carlin once said, “we buy shit we don’t need, with money we don’t have, to impress people we don’t like.” Abundance has made it all happen.

We are behaving in ways that offer us little meaningful rewards. And we’re working ourselves to the bone to do it. When you consider this rat race, this desperate attempt at social validation doesn’t make us happy; and then you consider the fact we’re destroying the environmental conditions we depend on to feed the consumer machine; then our civilisation is eating itself alive. This is psychotic.

Our technological sophistication has made us arrogant in our belief we’re in control. Sure, we can continue to achieve increases in output, but this ability means we have lost sight and perspective.

What’s required is to strip society back. It’s to get back to basics and focus on that which matters most. But no one will ever accept that our lifestyles are the problem. No one will ever acknowledge the need to give them all of the stuff up because the stuff we own, now owns us.

When looking at the risks it’s not a stretch to imagine a day, in the not-too-distant future, where we become reliant on that seed vault to protect our species from extinction. If we do, if the world around us is burning, the brutal reality will become clear. All of that stuff muddled us as a species. It led us down a path of oblivion. And none of it made us happier. That’s the saddest part of all of this. It’s only when billions of people are going hungry, that we’ll come to appreciate that which matters most.