The human population presents a profound moral dilemma

Ever since you were born the human population has been increasing by a billion people every 15 years or so. It seems normal, but this explosion in the human population, which began with the baby boomers at the end of the second world war, is totally detached from the human experience.

Throughout history disease, war, and starvation have wreaked havoc on societies. The black death, for instance, is estimated to have killed up to 200 million people in the fourteenth century. A human experience defined by suffering explains why it took thousands of years for the population to hit one billion people. That milestone came at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

The next billion came around a hundred years later, in 1920. The next billion came forty years later, in 1960. That’s when the human population went into overdrive. Four billion came in 1974; and five billion just thirteen years later. By 1999, six billion people roamed the Earth. By 2011, there were seven billion people. In 2022, the eight billion milestone was hit.

While population growth is slowing down, the UN estimates the human population will hit eleven billion by 2100. We’re having trouble creating sustainable societies as it is, so is it possible for eleven billion people to live sustainably on Earth?

To get to grips with that dilemma we really ought to think, what is it we need to sustain? And for whom do we want to sustain it?

What we need to sustain are the environmental conditions that are conducive to supporting thriving societies. For the simple reason that we want to sustain society.

So what do we need to sustain functioning societies?

If we break needs down to mere survival, what we need to sustain ourselves is sustenance. The good news when it comes to food is that we already produce enough to feed ten billion people. But that’s ignoring how that amount of food is produced. Agriculture has an enormous environmental impact and has become increasingly dependent on fossil fuels (for example to make fertilisers) which have greatly enhanced yields.

The impacts of the food system mean that it can’t be sustained in its current guise if we want to reduce environmental impacts. To sustain a population of eleven billion people you can forget about that population eating meat, and many other elements of modern diets, like having tropical fruit year-round, that have become basic expectations. But that’s just part of the bad news.

The UN estimates that in 2021 828 million people suffered from malnourishment. That’s over ten percent of the human population. It seems like a wild stat when we produce food for two billion more mouths, but hunger is the result of a failure of distribution. Even if we can increase the food supply and overcome the food distribution problem, thriving prosperous societies depend on much more than having enough to eat.

So, what do people need to live fulfilling lives?

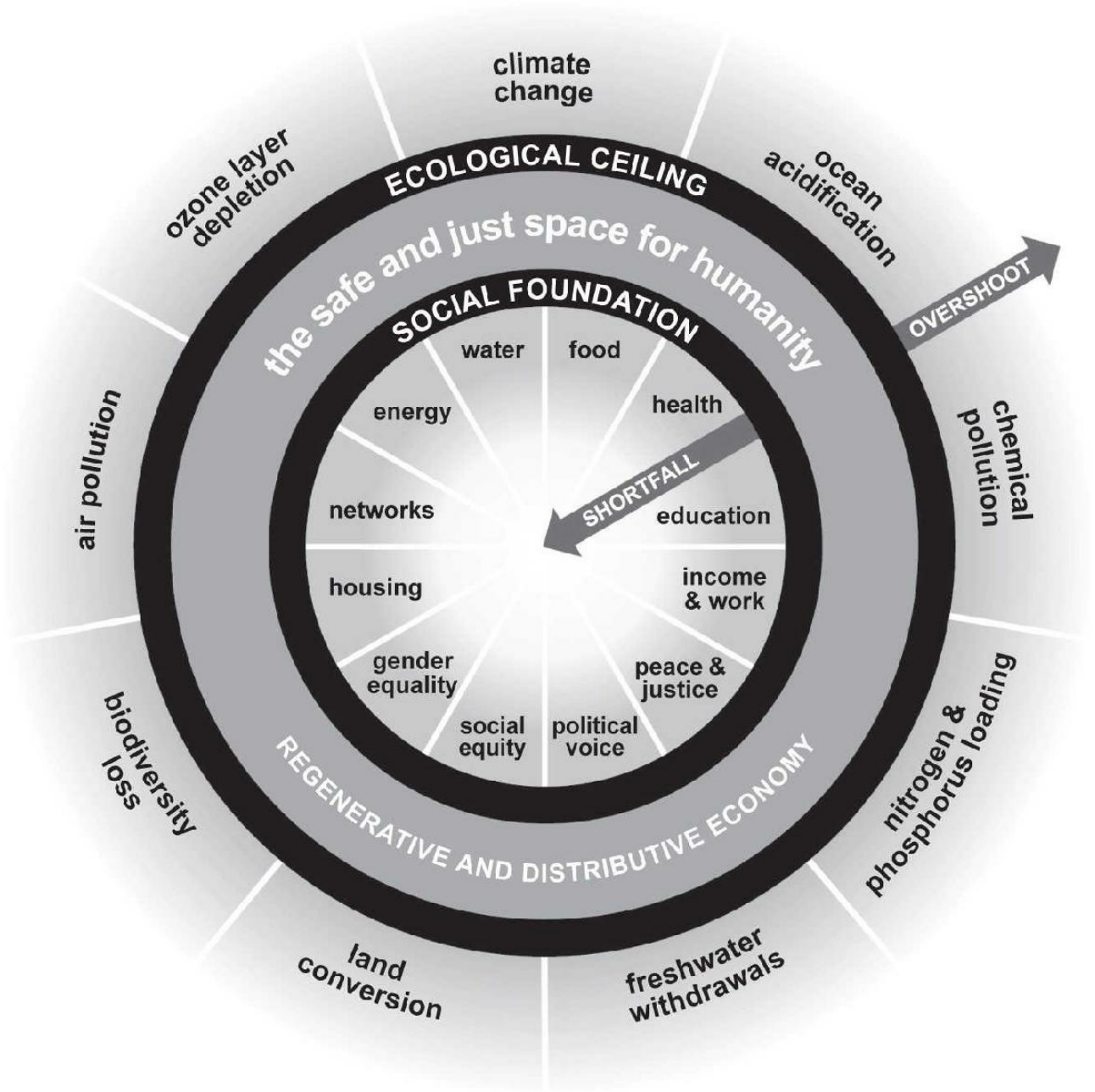

That’s exactly what the economist Kate Raworth has attempted to envision by designing the Doughnut. The inner ring of the Doughnut, as shown in the image, comprises twelve essential ingredients each person needs to live fruitful, fulfilling, prosperous lives.

The twelve social foundations include “sufficient food; clean water and decent sanitation; access to energy and clean cooking facilities; access to education and to healthcare; decent housing; a minimum income and decent work; and access to networks of information and to networks of social support.”

Creating a just space for humanity involves meeting the social foundations of each person. But we can’t create a just space without a safe environment.

The outer ring comprises nine earth system processes that are vital to maintaining the integrity of the natural world in its current state. Human activity influences processes in ways that lead to negative changes. The more pressure we place on a process the greater the risk that it crosses a boundary. The further the process is driven from the boundary, the greater the risk of triggering tipping points that move a process into a new unknown state.

The Doughnut provides a compelling vision of what a sustainable society living within the Earth’s carrying capacity looks like. It also shows us how far away we are from achieving it.

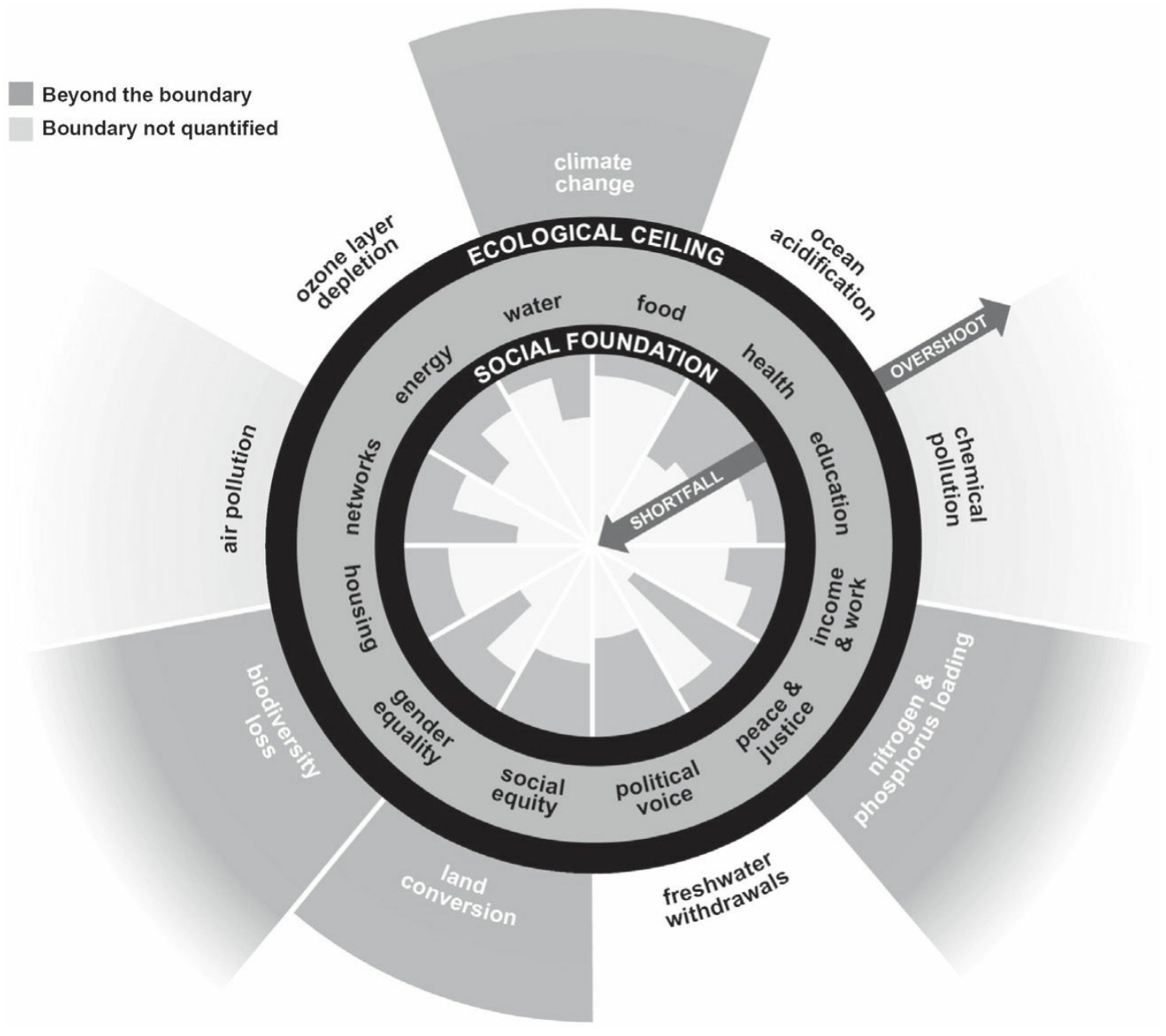

The image below shows that six of the nine planetary boundaries have been breached, increasing the risk the Earth system will tip into a new unknown state. On the social side, things don’t look much better. As Raworth points out;

“worldwide, one person in nine does not have enough to eat. One in four lives on less than $3 a day and one in eight young people cannot find work. One person in three still has no access to a toilet…one child in six aged 12–15 is not in school, the vast majority of them girls. Almost 40 percent of people live in countries in which income is distributed highly unequally. And more than half of the world’s population live in countries in which people severely lack political voice.”

What this all means is that all twelve social foundations are experiencing a shortfall. In the image, each foundation has a wedge protruding from it. The further away the wedge extends from the foundation, the more people are experiencing a shortfall.

Creating a safe and just space for humanity involves decreasing each shortfall so that every person has their social foundations met. Simultaneously, the six planetary boundaries must be moved back into the safe operating space while ensuring the other boundaries remain there.

That challenge would be monumental in itself, but add into the mix the a growing population and this is, by a long shot, the greatest challenge humanity has ever faced.

So why is a growing population so problematic?

Social development as we currently conceive of it means creating a just space involves undermining the ability to create a safe space. Expected growth rates of the global middle class highlight the conflict of interest.

It should be a cause for celebration that the global middle class — defined as those spending between $10 and $100 a day — is set to increase from two billion people today to over five billion people by 2030. More income will mean each person has a greater ability to meet their needs, helping to reduce some of the social shortfalls. But with increasing incomes comes a greater ability to consume more.

The growing middle class will want to travel, they’ll want to buy electronics, they may want to eat meat — and they have every right to do so. The problem is that with a greater ability to consume comes the increasing energy intensity of lifestyles.

In Prosperity without Growth Tim Jackson gives a sense of just how problematic the current development path is. He imagines a scenario where creating a just world is taken seriously, and global incomes converge by 2050. For that to happen, if rich countries grow at two percent each year, middle-income countries would need to grow around 7.6 percent each year, and low-income countries by almost 12 percent. In this hypothetical world, that would mean that by 2050 the global economy will be 11 times bigger than in 2016. Beyond 2050, if incomes continue increasing by two percent each year, the economy will be 30 times larger by 2100.

We already require 1.7 Earths to provide for the needs of society now. This means we’re living well outside the regenerative capacity of the Earth — a situation referred to as ecological overshoot. Overshoot translates into ocean acidification; it translates into the destruction (and extinction) of wildlife; it translates into the poisoning of soils.

Overshoot is the reason we have a climate crisis.

If we can’t provide the needs of eight billion people, what would overshoot look like if the economy is 30 times larger? Without decoupling economic growth from environmental impacts (a challenge that appears unfeasible), an economy 30 times larger than today is self-evidently impossible, because our resource and energy inputs will have to increase enormously which will exacerbate overshoot.

Ecological processes will be driven further away from the safe operating space, increasing the risk of triggering tipping points that will transform the natural world into an unforgiving new state. This will create profound stresses on our ability to continue to provide the social foundations for those who currently have them met, let alone reduce shortfalls for those who don’t. If this future hypothetical world sounds far-fetched, consider that global economic output is expected to grow by three percent per year until 2050.

So, getting back to that question. Can eleven billion people live sustainably on Earth? That really isn’t the question. The question behind the question is — what do the living standards of those eleven billion people look like? Or, to put it another way, can eleven billion people live sustainably on Earth while maintaining high living standards as enjoyed in the West? Those statistics wrapped up in never-ending increases in income reveal the answer is a categorical no.

Creating sustainable societies involves dramatically reducing our collective impacts on the natural world. And the finger of responsibility lies with the richest. Since 1990, the richest 10 per cent of the world’s population has been responsible for 52 per cent of carbon emissions, while consuming 20 times as much energy as the poorest 10 per cent. It all comes down to consumption habits that can’t be sustained. There is simply no getting around it. But, there’s also simply no way anyone is going to sacrifice their living standards for the common good.

In a society defined by have’s and have-nots, the aim of the game for the have’s is to remain have’s. And for the have-nots, it’s to join the haves. But the good life can only be sustained for the haves — for now, anyway — if the have-nots remain have-nots. That’s a morally outrageous state of affairs, but it’s one high-income countries feel entirely comfortable with.

As we progress into the twenty-first century the number of have-nots will likely swell. Why? As weather extremes become more aggressive it will lead to shortages, economic shocks and rampant inflation. How these impacts will be felt in daily life is through rising prices. That’s fine for the rich, but the global middle class will increasingly feel the pinch. For those just joining the middle class, it’s unlikely they’ll remain there for long.

Something is going to give in the end. That something will be the environmental conditions we depend on. The latter part of the twenty-first century will be plagued by hunger, mass migration and war. We’re going full circle and are set to return to the life of suffering that defined the human experience before the twentieth century. If we do, catastrophic losses to human life look set to follow in its wake.

More neoMalthusian nonsense, a diversion from the prime driver of an unsustainable future, fossil capitalism. There are two plausible scenarios: either climate hell kicks in because fossil fuels are not terminated in the near future, resulting in mass death with a global population crash, or the eco socialist alternative we are fighting for, the other world that is still possible with stabilization of global population. Population levels stabilize when women have power in society and poverty is abolished (see e.g., Kerala, India).

Animal agriculture is the leading driver of most areas of overshoot, making it imperative that we phase out fossil fuels and reform agriculture as soon as possible.

With switching to plant based diets and with reforesting pastures we could sequester decades of recent fossil fuel emissions [0], let the biodiversity rebound, repair water cycle, stop droughts, overfishing, while comfortably feeding 10 billion. [1]

Our soils are severely depleted. By rebuilding the soils with truly regenerative techniques, we could remove almost a decade’s worth of emissions with every 1% increase in carbon sequestration [2]. Techniques like syntropic or natural farming not only eliminate the need for external inputs but also achieve similar yields to industrial agriculture without using poisons and fertilizers. They work in harmony with biodiversity, rather than against it.

[0] https://journals.plos.org/climate/article?id=10.1371/journal.pclm.0000010#pclm.0000010.ref021

…eliminating animal agriculture has the potential to reduce net emissions by the equivalent of around 1,350 Gt CO2 this century. To put this number in perspective, total anthropogenic CO2 emissions since industrialization are estimated to be around 1,650 Gt.

[1] https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/917471

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jul/04/improving-farming-soil-carbon-store-global-heating-target