Incrementalism or paradigm shift —two distinctive camps at the forefront of transformation

It’s widely acknowledged that transformation is required to move to a sustainable future. But what exactly does transformation mean? Does it mean redesigning our economic system so that it produces goods and services differently? Does it mean redefining social success? Does it mean making changes to how businesses operate? None of this is made clear by saying we need transformation. But out of the haze of confusion, two distinctive camps have developed. These camps have very different views of the kind of transformation that’s required to move to a sustainable future.

The Incrementalists — there are plenty of governments and businesses that argue a sustainable future can be achieved through incrementalism. This is the idea that transformation is all about making slight tweaks to how we do things. Net zero is the most well-known of these incremental changes. The focus is on decarbonising economies and creating energy efficiencies. The underlying argument is that it’s not necessary to rock the boat (the boat being society and the economy) because while there are issues with the said boat, these issues aren’t systemic. We just need to make gradual changes to get rid of the bad bits that lead to undesired outcomes until we reach a point where the global economy and society have a minimal impact on the environment. Once achieved, we’ll have reached destination sustainability.

The paradigm shifters — in the other camp, there are plenty of climate scientists, ecological economists and environmental activists who argue a paradigm shift is required. A paradigm shift is also known as systems change, a regime shift or its most well-known synonym, a revolution. Calls for radical change centre on the fact that the global economy is too large and is the cause of catastrophic environmental impacts. The underlying argument is that it is the boat itself that is the problem. The issues caused by the boat are systemic and require nothing less than a total redesign of said boat. Only with a redesign of the economy and society can we reach destination sustainability.

So who is correct? To have a chance of answering what type of transformation is required we need to think about two questions. What is a society, and what is it about our societies that are unsustainable?

What is a society?

This may seem like an odd question to ask but society is what we want to sustain. So it seems reasonable that to determine what kind of transformation is needed, we need to understand exactly what a society is.

The thing about societies is they all have a series of shared characteristics. The most influential of these characteristics is culture. Culture is “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits.” Culture forms a rule system that governs behaviour and creates a shared understanding of the lived environment. Every society also has a language which is the communication system that allows us to talk. Language forms the basis of culture as it’s through talking and writing that we learn about the past, present and future. As well as culture and language, in Human Institutions, the sociologist Jonathan Turner argues all societies have an institutional core. This core includes;

- The economy — the organising principle used by society to provide the goods and services needed to fulfil human needs.

- Polity — a form of government that allows society to “function both internally (as a set of interacting subgroups) and externally (to interact with other groups), and to administer conflict (within the group and with other groups).”

- Religion — a belief system that seeks to explain and justify the relationship between individuals, the groups they belong to, the universe and our place in it.

- Kinship — a “set of norms specifying relationships among those related by blood…and those who are related by marriage.” In modern society, kinship revolves around the nuclear family that forms the household.

- Education — teaches us how to conform to social rules as well as learn skills that enable us to become functioning members of society.

- Laws — a rule system each member of society must conform to in order to remain a functioning member of society.

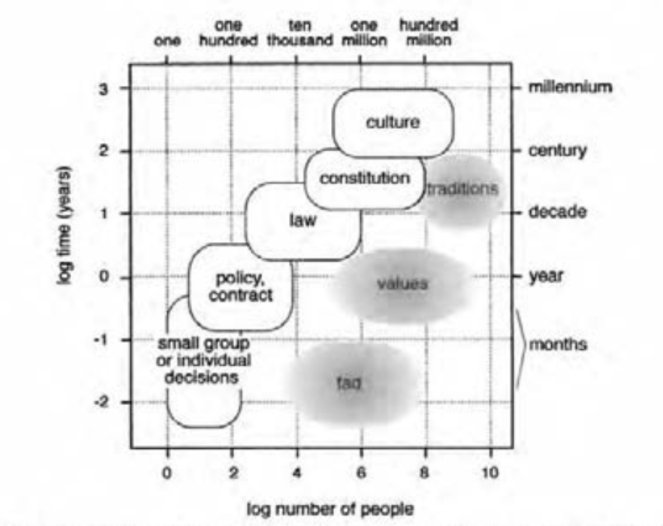

Each characteristic of society is universal, but how they’re expressed is wildly different. Take language, it forms the basis of culture, but there are nearly 7,000 languages in use. The shared characteristics of society combine to form a complex construct. Some scientists call this construct a ‘panarchy’. As shown in the image the social panarchy is a set of systems within systems with varying degrees of influence over the integrity of the construct. It’s this construct that creates an all-encompassing reality that makes up our day-to-day lives. The construct comprises larger systems on the top right which are formed slowly and have a greater influence over society.

Ideology is a vital component of the largest system, culture. It’s used to “justify and explain (to its own members, as well as outsiders) the characteristics of the society — its social structure (society), laws, delegation of authority (polity), division of labour, production, distribution and exchange of resources (economy), and its attitude to nature (religion, epistemology).”

The image of the social panarchy shows blocks of systems, but in reality, every system comprises multiple layers. Culture isn’t a blob on a map. It is a highly complex amalgamation of various systems that coalesce to create an agreed way of seeing the world. Every other ‘blob’ is a nested institution that works in service of the overarching ideology. Institutions are broadly defined as a culture’s norms and rules. Each institution performs “diverse and overlapping functions for their individual members and…are organized as relatively specific and semi-autonomous entities.” While institutions may appear semi-autonomous, every institution is interconnected.

Ideology informs the “structure of institutions, the nature of social cooperation and conflict, and the attitudes and predispositions of the population. All social relations are at the same time ideological relations, and all explicit ideological discourse is a form of social action.” Institutions, then, are designed in service of ideology and are mutually interdependent and reinforcing. Put simply, ideology acts like an invisible glue that binds each layer of society together.

Obviously, the world we see with our eyes doesn’t look like a set of systems within systems. We are all born with a natural capacity to learn culture, which we do through our socialisation. The process of socialisation and the fact it creates conformity to an ideology is crucial “to understanding resilience in social systems. Routines and even resources may suffer a loss of resilience, but as long as the structures of signification stay in place, the whole system will not transform radically, but rather will return to a previous equilibrium.”

Culture is what provides the overall system stability. For this reason, culture tends to be conservative and doesn’t change easily. This resilience to change is important because a “system of rules that changed at the whim of any individual would lose its effectiveness in the regulation of social life.” Aspects of culture can and do change with time, but the structure of the panarchy means cultural change happens slowly.

What is it about society that is unsustainable?

Well, it just so happens that ideology plays a fundamental role in what makes society unsustainable. The dominant ideology of our time is an economic one — free market capitalism. The key belief of capitalism, which influences essentially every element of our lives, is economic growth.

So what’s the issue with economic growth? Well, first of all, growth plays such a vital role in society because as economies expand they create more wealth. More wealth leads to higher incomes, the underlying assumption being that as incomes increase, so does human well-being. The issue with the core belief of modern society is that never-ending economic growth requires over-production and therefore over-consumption. What this all means is that over time the global economy requires more inputs of energy and resources from the natural world to produce an ever-increasing supply of goods and services. As it gets bigger its influence on the natural world has increased.

The global economy is now so big that we’re in a state of ecological overshoot. Overshoot is where our demands on the natural world exceed its regenerative capacity. And it’s not as if we’ve overshot by a little bit. We’d need 1.7 Earths to make our consumption levels sustainable. Growth and increasing environmental impacts go hand in hand, so more growth translates into more emissions, more waste, more habitat destruction, etc. That’s why plenty of ecological economists argue that moving to a sustainable society involves moving away from a growth economy and embracing degrowth. The aim of a degrowth economy is to contract the size of the economy while maintaining (or increasing) well-being. The problem, of course, is that this would undermine the core belief of modern society, which is unfeasible when we account for the fact that ideology is the glue that binds society together.

So what kind of transformation is required?

The structure of society explains why incrementalism is such a popular approach with governments and businesses. An incremental approach doesn’t question the underlying ideology governing society. It merely seeks to make slight adaptations from within the system. The fundamental problem with this approach is that it doesn’t question the causes of unsustainable behaviour, but simply looks to ease the pain by placing sticky tape over the effects.

Paradigm shifters, on the other hand, recognise that what makes our global society unsustainable is the norms, values and beliefs that emanate from a global culture that revolves around capitalism — and its core belief in economic growth.

The inescapable, unpalatable and highly inconvenient reality is that the ideology governing our lives leads to behaviour that creates catastrophic environmental impacts. So incremental change isn’t going to cut the mustard. What’s required is nothing short of the redesign of society around a different economic ideology.

The fundamental problem is that the structure of society means what we need — a paradigm shift — isn’t what we’ll get — incrementalism. This is because the core strength of society is that it’s highly resilient to change. This strength is proving to be a debilitating weakness because it results in constraints that define possibilities and impossibilities. In other words, we are trapped within a system that is highly resilient to systems change and continues to compel the behaviour that works to only reinforce the problem trying to be solved.

The only way society has been redesigned in the past (think French Revolution and Russian Revolution) is when the panarchy breaks down altogether. This eventuality is caused when points of weakness appear at multiple layers of the panarchy simultaneously. These vulnerabilities lead to social breakdown which then creates conditions that are ripe for revolution.

This scenario is becoming ever more likely because as we progress into the twenty-first century, environmental impacts will start to translate into increasingly hostile weather extremes. These weather extremes will create wave upon wave of social crises that will overwhelm the capacity of governments to respond. Once we reach a point where the effects of the ecological crisis begin to destabilise societies it will result in points of vulnerability at various layers of the social construct. These points of weakness could culminate in the global system breaking down and a revolutionary fervour sweeping across the planet. It’s that scenario that could trigger the required transformation needed to move to a sustainable future. Until then, the resilience of the social construct means any calls for radical transformation will continue to fall on deaf ears.

Paul, you’ve succinctly captured the stark contrast between incrementalism and the paradigm shift essential for a sustainable future. The discussion on tweaking the existing versus revisiting the prevailing economic ideology unveils a deep-rooted societal conundrum. Neogenesys proposes a novel middle ground, terming the change as an upgrade. It champions the advent of Civilization 2.0 through a reconfiguration of societal frameworks, aligning economic, social, and environmental ambitions towards a harmonious, sustainable future. The focus is on a thorough revamp of existing systems, nurturing innovation, and adopting a new “operating system” for humanity, designed for enduring resilience and prosperity.