The saying money makes the world go round, isn’t quite true. Behind the money are economists, who are some of the most influential people in modern society. They’re so influential because economics drives policy decisions that are crucial to how society functions. A key belief of modern economics is economic growth which has become a sacred goal. The issue is that this goal lies at the heart of why we are waltzing towards social collapse.

From big policy statements by governments, to taxes, to the price of a bag of pasta at your local supermarket, economics affects everything and everyone in ways few people understand.

John Maynard Keynes, one of the giants of economics, once said of his own field:

The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed, the world is ruled by little else. (The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, p. 383)

The purpose of the economy

More important than when economists are ‘right’, and ‘wrong’, is the underlying beliefs and assumptions they have. It is these beliefs and assumptions about how an economy should behave that feed policy-shaping society.

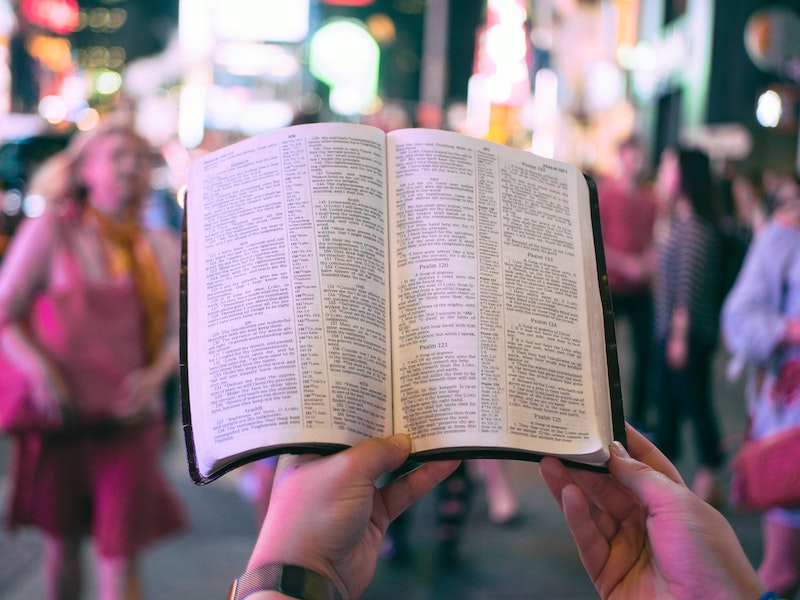

Economists all learn the same type of economics at university. As if they are attending a monastery. The idea is not to question what you are being taught but merely to absorb it to then go out into the world to preach.

Free-market capitalism is the economic doctrine all economists learn at university.

And the foundation of free-market capitalism is that economic growth brings social prosperity.

Economic growth is the purpose, the goal, the raison d’être of an economy. A truth as true as the idea we need air to breathe. It is a dogma, similar to a belief in god before it, that is so intertwined with the social structure we live within that if the belief were flawed, it would lead to social collapse.

There is virtually universal agreement amongst economists about the importance of growth in invigorating an economy. Growth translates into increased income for individuals in society. Increased incomes allow people to meet their needs and lead more fruitful, fulfilling lives.

Like a religion, all economists believe in the economic dogma that dominates — to question the economic doctrine would be to question the gospel.

So dominant is the ideology of free-market economics that there isn’t so much a field of economics with lots of differing opinions on how an economy should function. The argument is that the way we manage the economy is the only way it should be managed.

Economics as a science

What gives economists even more weight and influence is the idea economics is a science.

In 1968 the Nobel Prizes established the Prize in Economic Sciences. This was a symbolic moment because it placed economics in the same frame as the pure sciences of physics, biology and chemistry.

The implicit assumption is that economics is a science. But that is not the case. Economists may take a scientific approach to further understanding, but economics in itself is no science. The economy works off assumptions of how the economy should be. There is no ‘truth’ to how an economy should be structured in the same way that laws of science reveal truths about the natural world.

By classifying it as a science, the inherent assumption is that free-market capitalism is a ‘truth’. This is the way an economy should work. Any other economic system is an aberration that distorts the truth.

It’s as if we have ascended into some promised land— that this is as good as it is going to get.

Limits to growth

A slight problem with an economy that centres around growth is that indefinite growth on a finite planet is impossible. As (the economist) Kenneth Boulding put it, “anyone who believes that exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.”

The publication of The Limits to Growth (written by Donella Meadows, amongst others) in 1972 was groundbreaking as it questioned the possibility of growth on a finite planet for the first time.

The book predicted civilisation would collapse sometime in the 21st century as we come up against resource limits. The natural resources we depend on to sustain society being the limits to growth.

Economists attacked the book with ferocity as it questioned the dominant ideology of our time. Rather than have an open debate about whether growth on a finite planet is possible (when it clearly isn’t), they debunked the book.

Meadows questioning growth was like Galileo discovering the Earth did not lie at the centre of the universe.

It was to question the basic foundation’s economics is built on. To even engage in a debate would be to acknowledge that the study may have been correct. For those who believe their field is a science offering truths about the world, that is a can of worms they would rather leave unopened.

While economists savaged the report and its findings, nearly fifty years on the study is proving to be accurate. Our reliance on more means we’re starting to come up against limits.

And that can of worms is starting to bulge as it gets bigger and bigger.

A revolution of ideas

But economics hasn’t always been the dominant institution in society. For it to become so, it had to replace the church because, until the end of the eighteenth century, the church was the dominant institution — with the same power and authority as economics today.

What this shows is that societies and the beliefs underpinning them do change.

It was during The Enlightenment that the authority of the church began to be questioned. Many enlightenment thinkers argued religion was irrational and hampering the development of society.

Great thinkers like Adam Smith, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Locke were at the forefront of questioning the status quo. But while they questioned the current order of things, these men were not revolutionaries.

At the time, their ideas were just ideas. It was inconceivable to imagine these ideas would become dominant in society because if they did start to have social relevance, they would undermine the church’s dominance.

But then the French Revolution happened.

The French Revolution is arguably the most important event in human history because it destroyed the old order and the church’s place in society as the dominant institution. With the foundations of the old order crumbling, it made way for the ideas of the enlightenment thinkers to flourish.

It was only through the collapse of an old order, structured around specific ideas, that new ideas could spring forth. And it is those ideas that now lie at the heart of our social structure.

Heretics

We are now in a similar situation to the one those great enlightenment thinkers experienced. Economic thinking is far too rigid. In viewing itself as the truth, it believes it can not possibly be wrong.

When a fundamental of our economic system is wrong, we have ourselves a rather large problem.

Earth Overshoot Day is the symbol of how large the problem is. “Earth Overshoot Day marks the date when humanity’s demand for ecological resources and services in a given year exceeds what Earth can regenerate in that year.” Leading to an ecological debt we can’t pay back.

This year Overshoot Day landed on 29 July. That means we require 1.6 Earths to support the demands of humanity.

These demands will only get greater as the economic growth machine its never-ending pursuit of more.

What we need is an alternative that questions the integrity of free-market capitalism and, with it, the idea that an economy can keep on growing on a finite planet.

Herman Daly’s steady-state economics, Kate Raworth’s Doughnut economics and Tim Jackson’s prosperity without growth are just some of the ideas that question the model of growth. Each offers a different vision of what an economy without growth could look like.

Like the enlightenment thinkers before them, they are not revolutionaries, but their ideas are revolutionary.

They are heretics because they question the dominant ideology of our time. The issue is that we can only ever know if their ideas work if they replace free-market capitalism.

They won’t let go

That’s not an argument for maintaining the status quo, but merely reflects a larger issue in that for any new economic system to start to influence society it must replace teh current economic system.

The only way that the current economic system could be replaced is that it either breaks down and is replaced by another, or there is a social revolution, and the revolutionaries implement a new economic model.

Let’s think about the latter first.

For any new system to replace the current free-market ideology, it would require revolution on a scale that would make the French Revolution seem small fry. That’s because free-market capitalism has become the dominant way of doing things around the world. So it would need a revolution on a global scale, and each country would need to agree to adopt the same new economic mantra.

That seems unlikely.

Another scenario is that one of the key players, like the USA, has a social revolution that leads to a new economic system. And once it has, the new ideas then spread around the world — similar to how free-market capitalism became dominant in the first place.

That also seems unlikely.

Firstly, because it would require instability in a country, and if free-market capitalism was under threat in a superpower like the USA, other countries assist it to make sure the status quo remains.

Secondly, it would require a mass movement that is united behind a common ideology. This perhaps is the biggest obstacle because while there are alternative ideas for managing an economy, none has gained popularity in society.

Not many people will have heard of a steady-state economy in the same way they would know about socialism or communism, for example.

Implosion

The most likely scenario is that because we are in a trap of our own making, the system itself will break down.

If we imagine society as a car— the car only has one road to drive down (the path created by our economic beliefs). And for the car to keep functioning, it must continue to go faster. The problem is that in the distance, there is a giant wall blocking the road.

That wall is the limits to growth.

To avoid hitting the wall we need to transform the economy away from one that grows. There needs to be global recognition that growth on a finite planet can’t be sustained.

But because economists are blinded by the dogma of growth, they will never accept that growth can’t be sustained. We’re now too far down the road to turn back, and the economy has become far too embedded in this way of thinking.

To accept growth can’t be sustained would be to proclaim that a foundation of society is flawed. And so, rather than slow down, our foot remains firmly on the accelerator.

A globalised world can only work when all countries are singing from the same hymn sheet. While it would undoubtedly be painful to give up growth, the collapse of civilisation will be far more painful. Because economic thinking has become entrenched in a belief in growth at all costs, it looks like the only way anything will change is when we hit that wall.