Each year Larry Fink — the CEO of BlackRock — writes a letter to the CEO’s of companies BlackRock invest in. BlackRock is the world’s largest asset management company, so the message in this letter is a big deal for those CEO’s.

His letter in 2018 focused on the need to align purpose with maximising stakeholder — not shareholder — value. The need to take accountability for social and environmental factors is becoming increasingly important to investors, and corporations must consider these factors when doing business.

Fink remained consistent with this message in his letter earlier this year — focusing on a need to align purpose with profit. Previously, where corporate behaviour has led to dire consequences to the natural or social systems, these have been dismissed as mere outcomes of ‘doing business’. Externalities for society and government to deal with.

The corporation’s function was to maximise profit. Full stop.

The landscape has shifted. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) are factors corporations need to consider if they are to remain an attractive investment to investors. This trend is welcome. Gone are the days where corporations can make decisions based solely on maximising returns without considering the natural or social systems. Larry Fink’s 2018 and 2019 letters reinforce the idea that this way of behaving is no longer viable.

The Corporate Machine

But, why did corporations behave like this in the first place?

Because they were encouraged to do so by the very asset management companies that are now telling them this behaviour isn’t acceptable. Maximising returns on investment was what made you an attractive investment. How you did so wasn’t relevant.

From the perspective of senior executives, who drive decision making within corporations, if your external cues are directed towards reaping the greatest profit possible, and your KPI’s and targets are aimed at this objective — then decision making will naturally be centred on this factor. What may have seemed incomprehensible and illogical to the general population, was rational and made business sense from the corporation’s viewpoint.

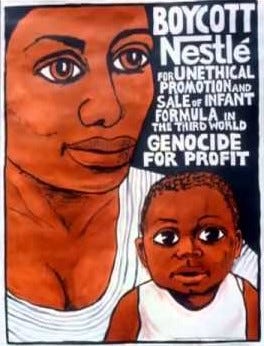

One such example of corporate rationale that springs to mind is the Baby Milk Scandal that revealed itself in the 1970s. Nestle and other multinational milk companies promoted the use of bottle feeding in poor communities by giving mothers milk solution for free.

This led to the mother’s natural milk drying up — but the solution didn’t remain free forever. As soon as the mothers were dependent on the milk, they were charged for it. Like drug dealers providing the vulnerable with free access to drugs, only to make them dependent, the corporations created a demand where there wasn’t one. After all, what milk could be better than a mother’s?

From the perspective of the corporations, this made business sense and allowed them to maximise returns on their product.

As the mothers often couldn’t afford the solution, it also led to infant illness and death.

For an outsider looking in, this business decision is evil — but from an executive’s perspective within the business, this behaviour is a consequence of a system that makes it necessary to disregard the negative consequences of business decisions.

Analysing the external environment — executives have always seen that profit is the ultimate success factor. If your job depends on ensuring that the corporation remains an attractive investment then you will soon become desensitised to these consequences of doing business.

Corporations are like Frankenstein’s Monster

The story of Frankenstein offers a useful metaphor for corporate behaviour.

When thinking of Frankenstein, most people think of an incoherent brute with a bolt running through his neck. But in Mary Shelley’s book, the monster is a far more nuanced character. When Viktor Frankenstein creates his monster, the ‘monster’ is not a monster at all. He has a conscious, a curiosity to explore the world and the people within it. Ultimately the monster has a desire to be accepted.

But when the monster attempts to interact with people, they are terrified of his appearance, their reaction and rejection of the monster results in the monster fearing people. That fear turns to hate, and it is only then that the ‘monster’ commits monstrous acts.

Viktor Frankenstein may have created the monster, but it was society’s interaction and rejection of him that led him to become a monster.

Upon being incorporated, I find it hard to believe a business set out with an objective to create social or natural destruction. However, corporations operate within a structure that encourages behaviour and business decisions that through another lens are monstrous.

Corporations are a product of their environment; this environment has encouraged them to make morally questionable decisions to maximise returns on investment. They have operated for the sole purpose and benefit of themselves and their shareholders. Acting in isolation, with a complete disregard for the consequences of their business decisions, because these are the rules of the game.

And to be successful, you need to play by the rules.

A Changing Landscape

This attitude of apparent disdain to the consequences of their behaviour has resulted in humanity being in the situation it is in now. The externalisation of the negative consequences of doing business has had dire consequences.

The natural world doesn’t offer an endless bounty of resources for us to use as and when we wish. It has limits and operates within a set of laws we have flouted for far too long. The rules of the corporate game go against the rules of the natural world.

Unfortunately, while the Earth is almost mind-boggling resilient to how we have treated it, there is an abundance of evidence that suggests that if we remain on our current path, it’s likely to result in the collapse of the system as we know it.

There will be no winners in this game of Russian roulette.

The growing importance of ESG is recognition that change is necessary if we are to mitigate against the worst impacts of corporate behaviour. If the manifestation of corporate behaviour is monstrous, then ESG could be a tonic that transforms the monster into a law-abiding citizen of Earth — a citizen who acknowledges and plays by the rules of the natural world. Rather than viewing the living planet and society as externalities of little consequence to the corporation, ESG makes executives consider the environmental and social consequences of business decisions.

The third facet of ESG — Governance — focuses on the management of a company. Corporations must be increasingly transparent about how they’re structured, what the culture of the company looks like, and how much executives are paid. So ESG is increasingly important in how corporations are valued by investors and is forcing them to reconsider their behaviour and responsibilities to the wider world.

ESG: a silver bullet or a smokescreen?

Is ESG the tonic that will transform corporations?

More important to consider is why are they changing their behaviour? Because the why, translates into the how.

Are they doing so out of recognition that their way of doing things isn’t sustainable? This sounds obvious but clearly, there is something we do that cannot be sustained if we are to avoid collapse of our economic system.

From the perspective of executives within corporations analysing the external environment — the why is focused on ensuring they remain an attractive investment. It’s something they feel they have to do, rather than something they want to do — a burden that takes away from the day to day function of the business, making profit.

The why acts as a pillar that translates into what a company does, and how it’s done. If the why centres on ensuring the business remains an attractive investment to investors, this is how it will be translated in terms of actions. The why has manifested in the form of Corporate, Social Responsibility (CSR) strategies. These strategies focus on making incremental changes that don’t affect the underlying structure of the corporation’s business model.

They’re not designed too.

They act as lip service, presenting a picture of responsibility to the wider world.

Reporting on sustainability alludes to this. A phrase which is often used in corporate sustainability reporting is ‘giving back’. After taking for so long, corporations now feel they have to ‘give back’ to the natural world and society. What exactly are they ‘giving back’?

Their businesses are entirely dependent on that very same natural world and society. The idea they’re giving something back is nonsensical. The arrogance of this phrase is breathtaking. Almost as if they are separate and different from the societies and the natural world they are entirely dependent on for their profiteering.

As discussed in a previous blog, the corporation is an expression of humanity’s ego — the all-powerful controller. Who behaves as if the Earth’s living systems can be used as and when we wish because these ‘resources’ are here for that purpose.

If corporations recognised that the current economic system cannot be sustained — if they understood the underlying why that is leading us to collapse — they would place sustainability at the core of their business. Sustainability and how the business does things would be interchangeable, it wouldn’t even be necessary to use the word sustainability, because this would be a core strategic driver — placed at the heart of the business.

A sustainability report or a section on sustainability in an annual report only works to demonstrate that corporations are not taking the threat seriously. Worse, they behave as if there isn’t a threat.

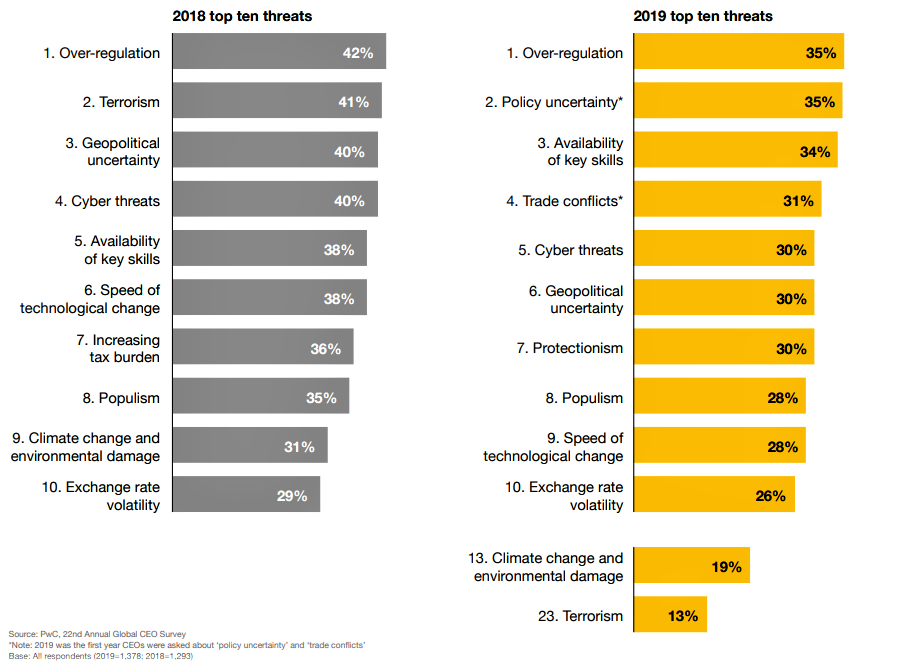

PwC’s Global CEO survey offers an insight into what CEO’s consider a priority in terms of threats.

When asked how concerned they were about various threats, Climate change and environmental damage were thirteenth on the list, falling from ninth in 2018. Not considered high on the priority list. This is reflected in how corporations relate to the problem. When you consider this list, every threat above this seemingly unimportant threat will be affected by climate change and environmental damage.

Once the effects of climate change become more prominent and alter the natural world, the trickle-down effects will be all-consuming. All threats will be a consequence of the changes that are going to take place in the natural world. We are, after all, dependent on the natural world to exist.

Embracing sustainability and transforming business models would be the most effective way to mitigate against all other threats.

Again, we need to consider all perspectives. From the perspective of executives, their blasé attitude to sustainability is understandable. They have a way of doing things, and they are experienced and good at what they do. Sustainability is the unknown — a threat in itself to their way of operating.

While ESG forces corporations to account for the consequences of decisions, the bottom line is still profit. ESG isn’t a silver bullet that will transform business models — where corporations take on the leadership and responsibility for initiating a transformation. It encourages incremental change, where corporations report on how they have become more socially and environmentally aware.

Greenwashing abounds.

But the problem is the business model, without accounting for this nothing will change. If we choose to identify the underlying flaws in our system and transform to a sustainable path we could avoid collapse. If we ignore the threats, the system as we know it will break down, and the crisis that results will force us to change.

One way or another — the way we do things is going to change. But nothing will change with incrementalism. The problem requires systemic change, and without transforming the structure of the system, the corporation will remain a monster.